By: Vanessa Raymond, Founder of Convene North

What might a highly desirable Arctic data portal look like? To answer this question, my research project, "Desire and Arctic Data Portals: A Qualitative Comparison" examines what Arctic data portals provide their users today. This research focuses on the implementation of 25 Arctic data portals and any data or metadata management practices they may support using comparative qualitative analysis. This research is funded by Convene North.

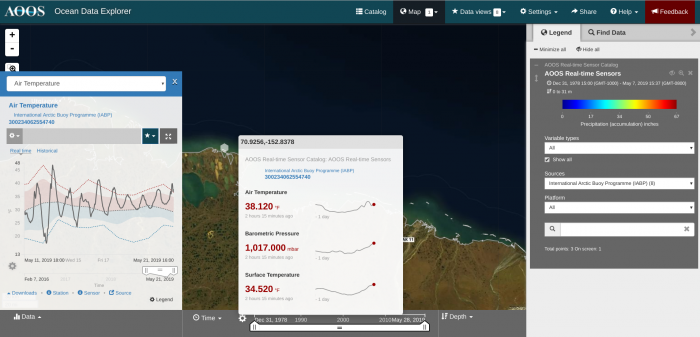

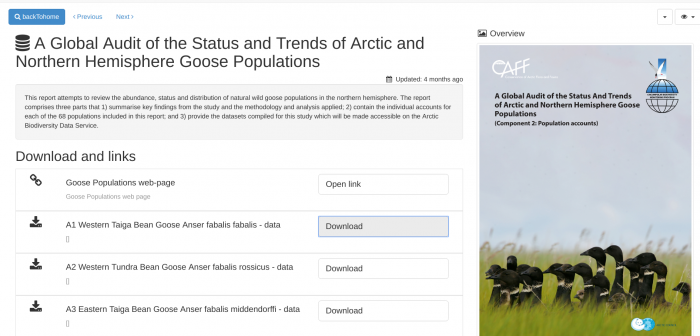

Data portals may house or reference data and metadata. Portals may have a variety of objectives. A data portal may be designed to visualize data, to showcase data, to encourage data play and manipulation, to find new audiences for data, to preserve and store data, or serve as a vehicle for downloading data. These objectives may have been identified by the software development team creating the portal, the research funder's data requirements, the portal funder, a principal investigator, the data needs of the research discipline, community members where the data was collected, or by any number of other stakeholders. More often than not, the portal design reflects the desires of multiple stakeholders.

Data is Emotional

Research data grows increasingly prolific and comprehensive, serving as an emerging source of power and knowledge. Some researchers celebrate the proliferation of research data, its increased precision, and the speed with which it is collected, processed, and manipulated. As a result of this proliferation of research data, data management and data portals become increasingly important for researchers and research communities.

Yet, as research data grows in scale and significance, researchers may grow weary, overwhelmed, or fearful about the management of their research data. At times, researchers may feel resentful, confused, uncertain, or frustrated about data management requirements from funders. Conversely, a researcher may feel joy or pride in sharing what they view as quality or highly prized data. When faced with new guidelines, researchers may feel left out or left behind by changes in data management standards, data processing techniques, or other expectations about data. Research, and research data, are emotional.

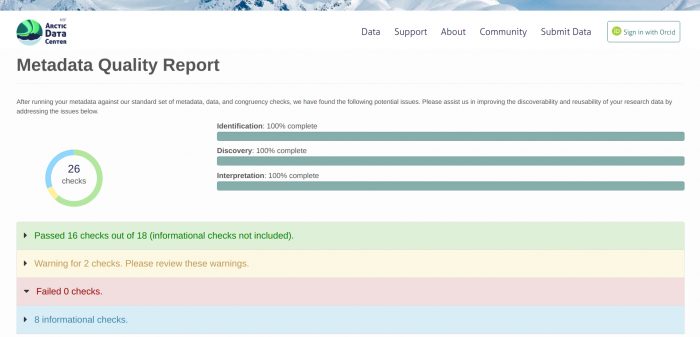

The desires and emotions that researchers have about their data carryover to the user's experience of Arctic data portals. Does the portal frustrate the researcher, or is it easy to use? Does the portal help the researcher meet important funder requirements? Does the portal help researchers publish their research, or hinder? Can the portal help the researcher to improve the quality of their data and metadata? Does the portal facilitate the sharing of a researcher's data in a way that all contributors can receive appropriate credit? What solutions does the portal provide for the researcher or Arctic data consumer?

Arctic Data Portals Today

This research, still in progress, examines 25 Arctic data portals using 65 points of comparison. The comparison points were sourced through grounded theory, an analytical process by which concepts and categories are sourced from the dataset. Results are not finalized for this work, however ongoing work is available for those curious to see the comparison-in-progress and add comments.

One important question that this analysis brings to light concerns Arctic data portals and the desire Arctic researchers have for open access and open data. While many portals have some components of open data—for example where data is downloadable by any visitor to the portal—many of the supporting components for open data and open science are not present in the Arctic data portals examined. These supporting components such as data versioning, data citation suggestions, digital object identifiers, downloadable metadata, downloadable processing scripts, and/or software components for reproducibility are mostly absent from Arctic data portals today.

Another question that this ongoing research brings forward is about the future of Arctic data portals. While most portals note their funders, no portal analyzed in this research publicizes the duration of their funding, future funding plans, or details about how the portal will be sustained and maintained going forward. This information could be important to Arctic researchers who may consider preserving their data with a portal, however the sustainability and longevity of a portal has broader implications within the Arctic research community. Some of this uncertainty can be alleviated by data and metadata sharing with other repositories, however this practice is not widely adopted in the portals examined.

A third question that is raised in the process of this research is about Arctic data portals' capacity to preserve and share Indigenous knowledge and traditional knowledge from Arctic Indigenous communities. This is a complex situation with much historical and cultural nuance. However, Indigenous data sovereignty efforts and Indigenous data management practices that are being adopted by non-Arctic Indigenous groups do not appear to be in use in Arctic data portals examined at this time.

Next Steps

The next steps for this research include refining the concepts and categories for analysis and potentially expanding the comparison to include additional Arctic data portals. Further effort will be required to ascertain future funding information and to get more detail on software components used in Arctic data portals that are a part of this comparison. The research is expected to be finalized in 2020.

For further information, contact Vanessa Raymond (vanessa [at] convenenorth.com).

About the Author

Vanessa Lee Raymond is a sociotechnologist interested in data ethics and technology for social good. She holds a M.A. in Arctic Governance with a focus on Arctic Security from University of Alaska Fairbanks, and a B.A. in Cultural Studies from Hampshire College. Vanessa is an IT project manager and founder of Convene North, an organization connecting Northern communities and environments to technological solutions. Prior to founding Convene North, Vanessa worked at the UAF Geographic Information Network of Alaska and the NSF Arctic Data Center.

Vanessa Lee Raymond is a sociotechnologist interested in data ethics and technology for social good. She holds a M.A. in Arctic Governance with a focus on Arctic Security from University of Alaska Fairbanks, and a B.A. in Cultural Studies from Hampshire College. Vanessa is an IT project manager and founder of Convene North, an organization connecting Northern communities and environments to technological solutions. Prior to founding Convene North, Vanessa worked at the UAF Geographic Information Network of Alaska and the NSF Arctic Data Center.