By: Chris Arp, Water and Environmental Research Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF); Katie Spellman, International Arctic Research Center, UAF; Laura Oxtoby, Water and Environmental Research Center, UAF; and Dana Brown, Institute of Arctic Biology, UAF

Watching river and lake waters as they develop first ice in the fall, grow to a solid stable cover over the winter, then break-up—often dramatically—in the spring is something that comes naturally to northern peoples. Whether watching in wonder, deciding when to set nets for early winter whitefish, warning villages of ice-jam flooding, or detecting responses to climate change, observing the ice cycle on rivers and lakes draws the interest of many. The NSF-funded Fresh Eyes on Ice (OPP-1836523, 2019-2023) draws on this natural motivation by engaging Alaska communities and citizen scientists to improve freshwater ice observations. Revitalizing and modernizing river- and lake-ice observations is being accomplished through archiving and analyzing existing historic datasets, remote sensing, field studies, real-time cameras and buoys, and community-based monitoring.

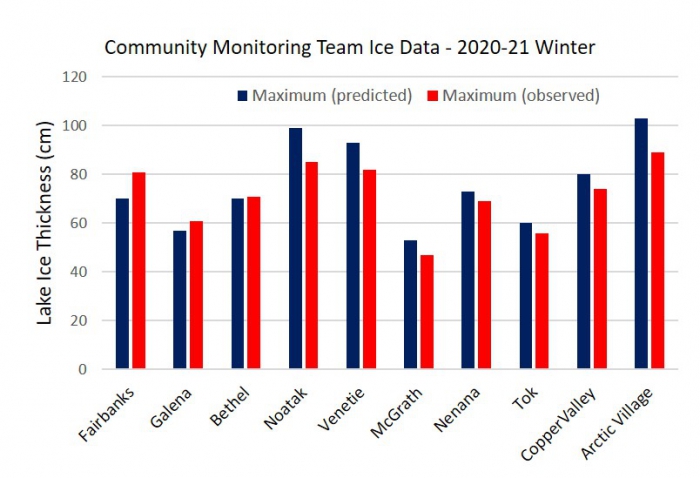

The recently published paper in The Cryosphere (Arp et al. 2020) documents changes in Alaskan river and lake ice since the 1960s from multiple citizen science initiatives. By fitting ice growth curves to measured ice thickness, standardized comparisons of maximum ice thickness and safe travel duration were made between lakes near northernmost Utqiaģvik and south to Anchorage and on rivers from Bethel next to the Bering Sea all the way to Eagle on Yukon River near Canada. This analysis shows a strong thinning ice trend in northern Alaska, high variability in other regions, and provides a solid baseline for future comparisons. To continue and expand on these records, Fresh Eyes on Ice is working with 14 communities and schools around Alaska to record ice thickness and snow depth through the winter (Figure 1). Science education is an important part of this program (see Broadening Participation in Freshwater Ice Science and Education with Fresh Eyes on Ice, Spellman et al., this issue), as is community engagement where students and teachers are encouraged to share results with their community and even through social media (Figure 2).

Community-based Monitoring Teams (CBMTs) are made up of a local expert teamed with a teacher and their classroom students in each community. The Fresh Eyes on Ice project encourages CBMTs to share their findings with other members of their community to promote ice safety and environmental awareness, as well as share and compare observations with other CBMTs.

The Fresh Eyes on Ice team originally planned to travel to Alaskan communities this winter including Galena, McGrath, Shageluk, and Bethel to work with students and teachers on special projects. We had hoped to learn more about local ice concerns from community members, while collecting ice data on lakes and rivers with transport by snowmachine at locations between the communities. However, due to COVID-19, two shorter field excursions focused work on the Tanana, Tolovana, and Kantishna rivers to record ice thickness and to gather in situ observations of persistent open-water zones (i.e., ground truth) to improve detections with satellite remote sensing. A brief in-person science education event was coordinated in the village of Nenana during the early March traverse and the team shared ice science techniques with interested community members. Even though temperatures were relatively cold in interior Alaska much of the 2020—21 winter, numerous open-water zones were discovered in January and a few stayed open into March. Real-time river ice cameras also document this slow freeze-up progress with all but one river camera showing a complete freezing over by mid-winter. Still partly open and now rapidly decaying is the Copper River just downstream of Tazlina River confluence where a camera is located in partnership with Wrangell – St. Elias National Park and Preserve (Figure 3).

See the Copper and other rivers around Alaska today via Fresh Eyes on Ice river cameras and submit your own break-up photos to the Ice Observer portal.

Watching these cameras document the melting-phase of the ice cycle can provide useful information to predict spring break-up and potential for ice jam flooding. Ice-watchful citizen scientists in Alaska can also share their break-up photos of rivers and lakes on social media Photos uploaded directly to the Ice Observer portal will go into a permanent archive and also go directly to scientists with the Alaska Pacific River Forecast Center to aid in river flood forecasting. Becoming an active and sharing observer of the ice cycle is what the Fresh Eyes on Ice project is all about! With new support from NASA to expand observations of river ice (see Spellman et al., this issue) we hope to involve a much broader group of citizen scientists in observations of river break-up, freeze-up, and all the interesting ice dynamics in between. Though community eyes are currently focused on watching for hazards as ice covered rivers transition to open water, an emerging focus identified by Fresh Eyes on Ice engagement with communities is the increasingly later and prolonged freeze-up season. Expect new discoveries to emerge as this project increasingly focuses on the start of the ice cycle.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the many educators, youth, families, and community scientists in the community-based monitoring teams, and the many observers contributing their photos from across Alaska. Karin Bodony, Allen Bondurant, Sarah Clement, Melanie Engram, Tohru Saito, Theresa Villano, and Peter Webley have been critical to the program development and implementation in the first two years. Fresh Eyes on Ice community-based monitoring and learning research is funded through the National Science Foundation Navigating the New Arctic and Arctic Observing Network programs (OPP-1836523) and the expanded photo observation effort is funded through the NASA Citizen Science for Earth Systems Program.

Reference

Arp, C.D., Cherry, J.E., Brown, D.R.N., Bondurant, A.C., Endres, K.L. 2020b. Observation-derived ice growth curves show patterns and trends in maximum ice thickness and safe travel duration of Alaskan lakes and rivers. The Cryosphere 14:3595—3609.

About the Authors

Chris Arp is Research Associate Professor with the Water and Environmental Research Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Chris studies how Alaskan lakes and rivers fit into the broader hydrologic cycle, are responding to changing climate, and serve as habitat and other socio-ecological functions. The Fresh Eyes on Ice project is his first endeavor into community-based monitoring and science education.

Chris Arp is Research Associate Professor with the Water and Environmental Research Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Chris studies how Alaskan lakes and rivers fit into the broader hydrologic cycle, are responding to changing climate, and serve as habitat and other socio-ecological functions. The Fresh Eyes on Ice project is his first endeavor into community-based monitoring and science education.

Katie Spellman is an Assistant Professor at the International Arctic Research Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. She is a life-long Alaskan who splits her research evenly between ecology and education research, with a focus on citizen science in a rapidly changing climate as a focus area at the interface of the two disciplines. She is dedicated to empowering diverse youth to address climate issues in their community through science.

Katie Spellman is an Assistant Professor at the International Arctic Research Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. She is a life-long Alaskan who splits her research evenly between ecology and education research, with a focus on citizen science in a rapidly changing climate as a focus area at the interface of the two disciplines. She is dedicated to empowering diverse youth to address climate issues in their community through science.

Laura Oxtoby is a research professional with the Water and Environmental Research Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Laura splits her research time between aquatic ecology and learning sciences. She is passionate about working with youth—from providing safe spaces for homeless youth to gather, to offering projects that span art, science, and outdoor adventure for youth to explore.

Laura Oxtoby is a research professional with the Water and Environmental Research Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Laura splits her research time between aquatic ecology and learning sciences. She is passionate about working with youth—from providing safe spaces for homeless youth to gather, to offering projects that span art, science, and outdoor adventure for youth to explore.

Dana Brown is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Institute of Arctic Biology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. She uses satellite remote sensing to study how the seasonality of river ice is changing and to map the spatial dynamics of the ice cycle to help foster safe travel.

Dana Brown is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Institute of Arctic Biology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. She uses satellite remote sensing to study how the seasonality of river ice is changing and to map the spatial dynamics of the ice cycle to help foster safe travel.