By: Matthew Sturm, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Geophysical Institute, et al.

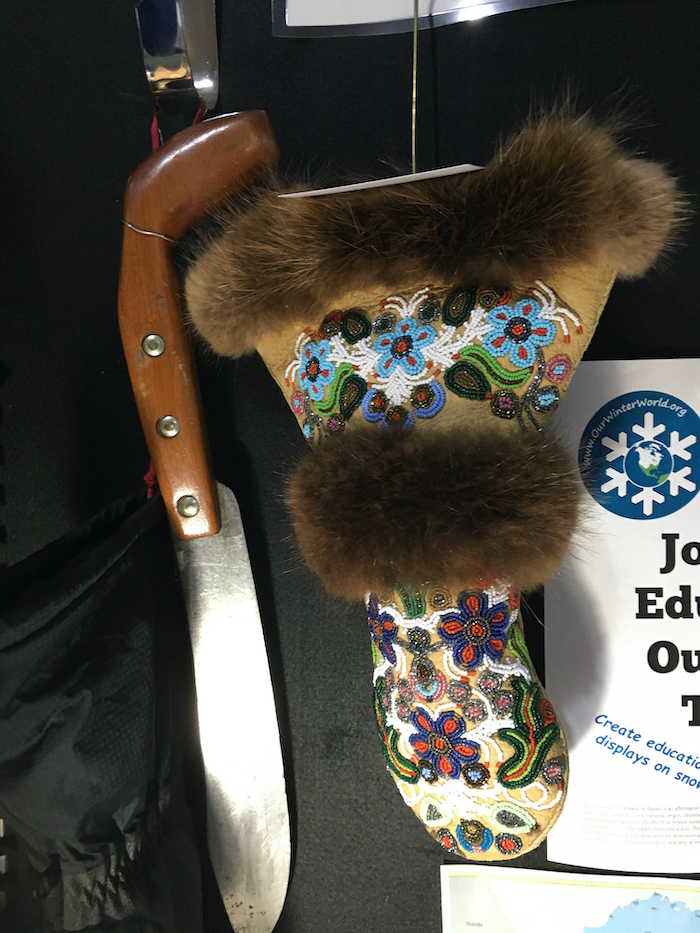

In the Arctic, snow comes in September and stays through May, providing residents with a winter lasting over 250 days. Not surprisingly, snow is deeply embedded in all Arctic cultures. Skis more than 5,000 years old have been found in Norway, and snow knives more than 2,500 years old have been found in Greenland. In our experience, people in the North look forward to freeze-up and the development of a snow pack because it means they get out their snow machines and travel. Snow in the Arctic can mean freedom.

(Editor's note: for information about the Gwich'in people, see here.)

With funding from the National Science Foundation, we have begun an Informal Science Learning (ISL) project focused on snow (NSF 1810778: Snow: Museum Exhibit, Educational Outreach, and Learning Research). The project has three components: (1) visits to Alaska villages where we host snow-themed community science nights and engage kids in the schools in learning about snow science; (2) design and production of a 2,000 square foot traveling museum exhibition on snow at the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI) in Portland; and (3) research exploring how cultural background affects learning in museum settings (led by the Center for Science and Industry (COSI) in Columbus, Ohio). The snow project builds on the work of a prior NSF award, (NSF 1423550: The Hidden world of Permafrost) that had similar deliverables of outreach programs, a traveling exhibition, and learning research.

Informal Science Learning (ISL) is learning in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) that takes place outside of formal classroom settings. Projects like this start with "front-end" research, which explores what the public knows about and feels towards the topic. Our front-end research indicated that virtually everyone polled had some personal connection with snow, generally favorable, and they often told us their epic snow stories (e.g., sled crashes, blizzards). When it came to snow science, however, there were surprising gaps in basic knowledge—even how many arms a snowflake has. We saw this combination of genuine interest and lack of scientific awareness as fertile ground for all three project components.

Alaska Village Visits

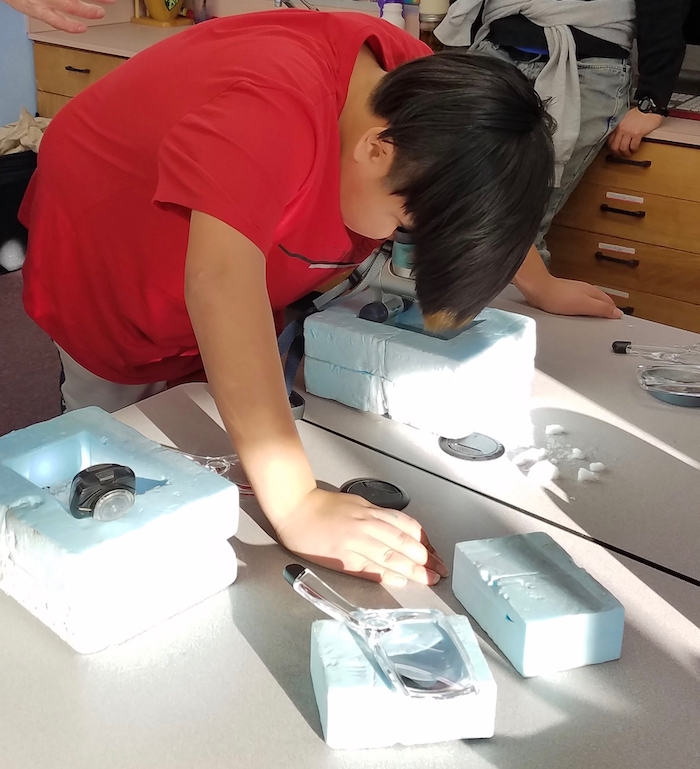

To date, our team has visited three villages in Alaska (Bethel, Tanacross, and Tok) and participated in a public outreach event at Denali National Park. We have developed a series of indoor and outdoor learning activities that use snow to demonstrate scientific principles ranging from water's molecular structure, to climate and solar radiation. School activities include snow pit measurements and snow crystal observations, snow albedo investigations, and an avalanche dynamics demonstration. These learning experiences engage kids in using authentic field techniques and scientific tools for observing and measuring snow and facilitate connections between these observations and measurements and their scientific and practical significance. The community science nights feature some of the same activities, plus additional table-top displays and materials, and a shared dinner with the village. As in our prior project on permafrost, which took us to 47 villages, the community science nights encourage mutual sharing of stories, experiences, and knowledge related to snow.

Traveling Museum Exhibit

In design of the exhibit at OMSI, beginning with a front-end study to explore public knowledge and attitude about snow science, our conceptual plans have matured into experience design and exhibit prototypes intended for visitor testing (a bit of a challenge with the museum closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic). Interactive exhibits highlighting snowflakes, snowfall, snow as a water source, and snow's role in the Earth's climate, are in development. Installation of the exhibition at OMSI is planned for early summer 2021. After its six-month venue in Portland, the snow exhibition is expected to travel to museums across North America for eight years or longer.

Effects of Cultural Background on Informal Learning

The third component involves investigating the role culture plays in ISL. All visitors coming to a museum exhibit or science night enter with a unique viewpoint that derives from personal experience and cultural background. Because the snow topic generates a full range of viewpoints, the COSI part of our team can study how these varied viewpoints affect learning. That information will help exhibit designers create better learning experiences. This research is being conducted through online and in-person surveys.

Due to COVID-19-related closures of public facilities, the spring of 2020 has been a challenging time for all of us, and particularly challenging to a project that is fundamentally about public engagement. Both OMSI and COSI are closed now, and travel to Alaskan villages is restricted. We are focusing instead on activities such as, moving the cultural study and visitor testing forward by electronic means, we have just completed a book for the general public on snow (Field Guide to Snow) that will come out in December, we are launching the website Our Winter World (soon to be available), and we are working together from our homes to advance the exhibition design remotely.

About the Author

Matthew Sturm, the lead author of this article, came to Alaska in 1973 and began doing snow research in 1981 at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. He continued that work for 26 years with the US Army Cold Regions Laboratory Alaska, then "retired" in 2012 and returned to his roots at Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska, where he still continues to pursue his passion about snow. Contributors to the article include, Maria Berger and Anika Pinzner, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Geophysical Institute; Margaret Rudolf, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Northern Studies; Deborah Wasserman and Dolly Hayde, Center for Research and Evaluation at the Center for Science and Industry (COSI) in Columbus, Ohio; Victoria Coats, Allyson Woodard, Syrrah Lee, Molly Schmitz, and Holly Hawk, Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI); and Angela Larsen and Kelly Kealy, Goldstream Group.

Matthew Sturm, the lead author of this article, came to Alaska in 1973 and began doing snow research in 1981 at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. He continued that work for 26 years with the US Army Cold Regions Laboratory Alaska, then "retired" in 2012 and returned to his roots at Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska, where he still continues to pursue his passion about snow. Contributors to the article include, Maria Berger and Anika Pinzner, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Geophysical Institute; Margaret Rudolf, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Northern Studies; Deborah Wasserman and Dolly Hayde, Center for Research and Evaluation at the Center for Science and Industry (COSI) in Columbus, Ohio; Victoria Coats, Allyson Woodard, Syrrah Lee, Molly Schmitz, and Holly Hawk, Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI); and Angela Larsen and Kelly Kealy, Goldstream Group.