By: Jacqueline Richter-Menge, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Institute of Northern Engineering, Fairbanks, Alaska; Matthew Druckenmiller, National Snow and Ice Data Center, Boulder, Colorado; and Martin Jeffries, Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory of the Engineer Research and Development Center, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Hanover, New Hampshire.

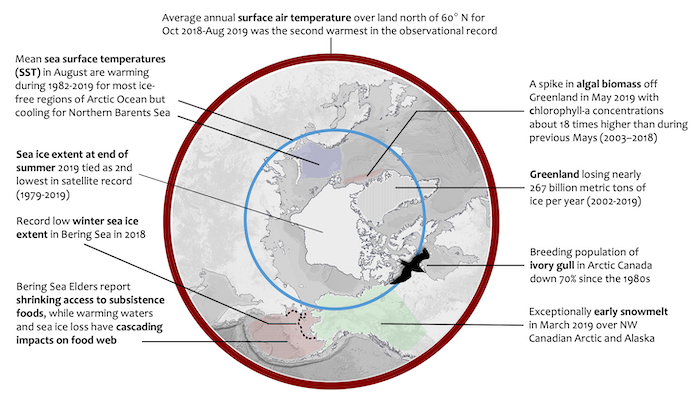

Arctic Report Card 2019, an interagency and international publication coordinated by NOAA, was released on 10 December 2019 during the American Geophysical Union (AGU) Fall Meeting in San Francisco, California. In its 14th year, the peer-reviewed Arctic Report Card (ARC) provides comprehensive summaries of key land, ice, ocean, and atmosphere observations made throughout the Arctic in the context of historical records. ARC 2019 includes 12 essays prepared by more than 80 scientists from 12 countries and, for the first time, featuring a contribution by Alaska Native peoples — Voices from the Front Lines of a Changing Bering Sea. The report makes clear that Arctic ecosystems and communities are increasingly at risk due to continued warming and declining sea ice (Figure 1).

At the center of the changes observed throughout the Arctic is the persistent warming of the surface air temperature, which began around 1980. The annual-average land-based surface air temperature anomaly for October 2018-September 2019 was +1.9°C, which is the second highest value (after 2015-2016) since 1900. Annual-average Arctic air temperatures for the past six years (2014-19) all exceeded previous records since 1900.

On land, the warming surface air temperature is causing a decrease in the extent of the Arctic snow cover, an increase in the overall amount of Arctic vegetation, and warming and thawing of permafrost. Thawing permafrost detrimentally affects municipal infrastructure, homes and facilities along shorelines, and Indigenous Peoples' traditional means for storing food in ice cellars. Warming conditions also promote the microbial conversion of carbon that is stored in permafrost into carbon dioxide and methane. These potent greenhouse gases are released to the atmosphere in an accelerating feedback loop to global climate warming. The Greenland ice sheet is also melting under the persistent rise of surface air temperatures and, as a result, contributing to global average sea level rise at a current rate of about 0.7 mm per year. During the 2019 melt season, the extent and magnitude of ice loss over the Greenland ice sheet rivaled 2012, the previous year of record ice loss.

In the marine environment, the decline in the extent and thickness of the Arctic sea ice cover is also directly linked to the warming air temperatures. In 2019, the Arctic sea ice cover remained younger, thinner, and covered less area than in the past. In March 1985, 33% of the ice pack was very old (>4 years), thick multiyear ice. In March 2019, this older and more resilient ice constituted only about 1% of the ice pack, meaning that its areal extent has declined by 97% in the last 34 years. The declining trend in the extent of the sea ice cover is directly linked to observed changes in the sea surface temperatures. In most regions of the Arctic Ocean that are ice-free in August, mean sea surface temperatures for that month show significant warming from 1982—2019. Recent declines in Arctic sea ice extent have also contributed substantially to shifts in patterns of biological primary production throughout the Arctic Ocean. All regions of the Arctic Ocean have exhibited increasing ocean primary productivity over the 2003—2019 period, with the most pronounced increases observed in the Eurasian Arctic, Barents Sea, and Greenland Sea.

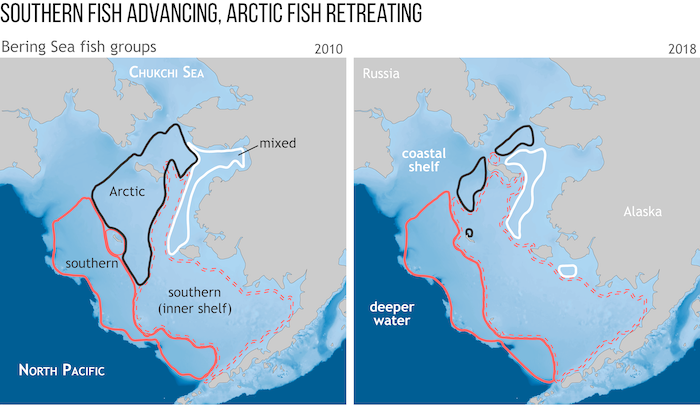

Recent conditions in the Bering Sea offer an excellent, albeit disquieting, example of the strong connections within the Arctic marine environment. The eastern half of the Bering Sea has a broad, shallow shelf that enables an exceptionally productive ecosystem, supporting large numbers of sea birds and marine mammals, the subsistence harvests that numerous Indigenous communities depend on, and more than 40% of the U.S. catch of fish and shellfish (valued at > $1B annually). For the past two winters (2018 and 2019) record low ice extent in the Bering Sea caused bottom water temperatures to rise. In 2018, these conditions created a wide corridor allowing sub-Arctic fish species to move northward into regions typically occupied by northern shelf and Arctic species (Figure 2).

Coming full circle, the decreasing extent of sea ice and snow cover along with the melting Greenland ice sheet leads to an acceleration in the rate of warming of surface air temperatures in the Arctic. This cycle is a critical reason why the Arctic has warmed at more than twice the rate of the global mean since the mid-1990. This warming is transforming Arctic ecosystems and presenting unique challenges for the region's Indigenous peoples who rely on the stability of the environment for cultural and economic well-being, as well as for subsistence foods taken from their local lands and waters. The impacts of a changing Arctic are not confined to those who live there. Through global sea-level rise, the release of permafrost carbon, and its role in regulating global weather patterns, the Arctic is vitally connected to people worldwide.

This article was adapted from the 2019 Arctic Report Card.

Further information, essays, and contact information for comments and questions are available on the Arctic Report Card: Update for 2019.

About the Authors

Jackie Richter-Menge began her Arctic research career in 1981, when she joined the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL) in Hanover, New Hampshire. Jackie retired from CRREL in 2017 but continues to do some work via an affiliation with University Alaska Fairbanks. Her research activities focus on developing a more comprehensive understanding of the Arctic sea ice cover, providing observations that can be used to advance forecasts in support of near real time operational needs, and future projections associated with global climate variability. In 2016, Jackie was appointed to the U.S. Arctic Research Commission by President Obama.

Jackie Richter-Menge began her Arctic research career in 1981, when she joined the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL) in Hanover, New Hampshire. Jackie retired from CRREL in 2017 but continues to do some work via an affiliation with University Alaska Fairbanks. Her research activities focus on developing a more comprehensive understanding of the Arctic sea ice cover, providing observations that can be used to advance forecasts in support of near real time operational needs, and future projections associated with global climate variability. In 2016, Jackie was appointed to the U.S. Arctic Research Commission by President Obama.

Matthew Druckenmiller is a Research Scientist with the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) at the University of Colorado Boulder. Since 2006, Matthew has worked within the coastal regions of Arctic Alaska, investigating the connections between changing sea ice conditions and marine mammal habitat and local Indigenous community use of sea ice for hunting and travel. Currently, he serves as the coordinator of the Sea Ice Action Team within the Study of Environmental Arctic Change (SEARCH) and co-leads the Exchange for Local Observations and Knowledge of the Arctic (ELOKA) Program at NSIDC—a program that explores novel approaches to community-led data management, community-based environmental monitoring, and supporting data sovereignty.

Matthew Druckenmiller is a Research Scientist with the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) at the University of Colorado Boulder. Since 2006, Matthew has worked within the coastal regions of Arctic Alaska, investigating the connections between changing sea ice conditions and marine mammal habitat and local Indigenous community use of sea ice for hunting and travel. Currently, he serves as the coordinator of the Sea Ice Action Team within the Study of Environmental Arctic Change (SEARCH) and co-leads the Exchange for Local Observations and Knowledge of the Arctic (ELOKA) Program at NSIDC—a program that explores novel approaches to community-led data management, community-based environmental monitoring, and supporting data sovereignty.

Martin Jeffries has been with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL) since September 2018; he has particular responsibility for strengthening the Arctic science and engineering portfolio. As a researcher at the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF) between 1985 and 2014, he investigated sea ice in Antarctica and the Arctic Ocean, ice shelves and ice islands (tabular icebergs) in the Canadian High Arctic, and lake ice in Alaska. From 2006 to 2014, he was detailed first to the National Science Foundation, where he was the first Program Director for the Arctic Observing Network, and then to the Office of Naval Research (ONR), where he was an Arctic Science Advisor and Program Officer for Arctic and Global Prediction, and finally to the U.S. Arctic Research Commission as a Science Advisor. Immediately upon retiring from UAF in 2014, he became a career civil servant with ONR, from where he was detailed to Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) in the Executive Office of the U.S. President between February 2016 and March 2018.

Martin Jeffries has been with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL) since September 2018; he has particular responsibility for strengthening the Arctic science and engineering portfolio. As a researcher at the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF) between 1985 and 2014, he investigated sea ice in Antarctica and the Arctic Ocean, ice shelves and ice islands (tabular icebergs) in the Canadian High Arctic, and lake ice in Alaska. From 2006 to 2014, he was detailed first to the National Science Foundation, where he was the first Program Director for the Arctic Observing Network, and then to the Office of Naval Research (ONR), where he was an Arctic Science Advisor and Program Officer for Arctic and Global Prediction, and finally to the U.S. Arctic Research Commission as a Science Advisor. Immediately upon retiring from UAF in 2014, he became a career civil servant with ONR, from where he was detailed to Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) in the Executive Office of the U.S. President between February 2016 and March 2018.