The Issue

The Bering Sea supports one of the largest, most profitable food fisheries in the world. Commercial fisheries are the largest private-sector employer in Alaska. The extent, duration and timing of sea ice advance and retreat are changing dramatically in the warming Arctic, and this accelerated transformation affects food webs on which commercially important fisheries depend. In the eastern Bering Sea, the availability and distribution of some commercially important fish species currently used for human consumption depends on adequate sea ice.

Why it Matters

Fishing is the core economy for much of coastal Alaska where fish harvesting and processing often provide the only significant opportunities for private sector employment and where fisheries support businesses that provide property and sales tax as the largest source of local government revenues http://www.akrdc.org/fisheries. Nearly two million metric tons of Pacific cod, walleye pollock, and salmon, as well as a variety of other fin fish and crab, are harvested annually from the Bering Sea, accounting for over half of total U.S. harvest volume and almost a third of U.S. harvest value http://labor.alaska.gov/trends/nov17.pdf.

Changes in fish-stock abundance and distribution impact the harvests, as well as the economies of communities participating in the harvests and their processing. Understanding and predicting these changes enables decision-makers to adapt fisheries management strategies, for example, adjusting the total allowable catch of a given species to reflect its predicted future abundance.

State of Knowledge

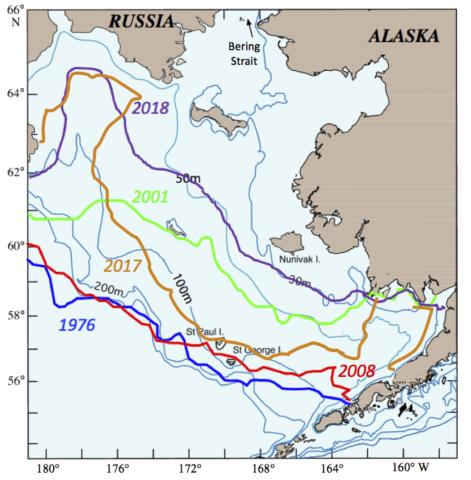

Most fisheries production of the eastern Bering Sea occurs on the southeastern shelf. Until recent years, the eastern shelf has been reliably covered by sea ice during the cold season1. In addition to providing a surface for ice algae to grow, sea ice over the southeastern shelf affects fish and fisheries in many ways. Ice cover thwarts fishing activity from large areas of the shelf in winter. The cold (< 2 °C) water that forms on the shelf where ice has lingered and melted deters predatory adult arrowtooth flounder, adult Pacific cod, and adult walleye pollock. Hence, it provides a potential refuge for juvenile walleye pollock and other forage fish more resistant to the cold2.

The sea ice also supports ice algae on its underside. These algae are an important food for zooplankton in spring. Later, these zooplankton are an important food for the juveniles of commercially important fish3,4. If the ice melts too early, the zooplankton do not get sufficient ice algae. The fish then have too few large zooplankton to consume for nourishment. Recent research has shown a strong correlation between the abundance of zooplankton in summer and the survival of harvestable, young-of-the-year walleye pollock and Pacific cod5,6. Thus, sea-ice-cover in spring is linked, through zooplankton, to the productivity of eastern Bering Sea pollock fisheries.

As the eastern Bering Sea warms, sea ice is declining. The production of pollock, cod, and possibly other species is likely to diminish. Many temperate species will move northward and become less accessible to fisheries based in the southern Bering Sea. However, the ability of boreal fish species to survive in the northernmost Bering Sea and Arctic Ocean may be limited. The cold, salty brine that results from sea ice formation creates bottom waters over the northern shelf that are too cold for most fish species to survive.

Where the Science is Headed

Climate and atmospheric scientists are working to predict the future climate of the eastern Bering Sea7. For commercially important fishes, oceanographers are developing models that will permit predictions of the amount of young fish that will survive to harvestable size based on future climate conditions. At present, models are relatively skillful in predicting the survivability of young-of-the-year pollock based on the amount of large, lipid-rich zooplankton over the southern Bering Sea shelf. While present ability to predict the abundance of these zooplankton based on physical attributes of the ocean is limited, understanding mechanisms affecting their productivity is critical for predicting the effects of sea-ice loss on commercially-important fisheries, such as that for walleye pollock.

Image Source: http://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2014/10/ecosystem-based-fishery…

Key References

- Sullivan, M.E., Kachel, N.B., Mordy, C.W., et al. 2014. Sea ice and water column structure on the eastern Bering Sea shelf. Deep-Sea Res. II 109: 39-56.

- Mueter, F.J., Litzow, M.A. 2008. Sea ice retreat alters the biogeography of the Bering Sea continental shelf. Ecol. Appli. 18: 309-320.

- Hunt, G.L., Jr., Ressler, P.H., Gibson, G.A., et al. 2016. Euphausiids in the Eastern Bering Sea: A synthesis of recent studies of euphausiid production, consumption and population control. Deep-Sea Res. II 134: 204-222.

- Wang, S.W., Budge, S.M., Iken, K., et al. 2015. Importance of sympagic production to Bering Sea zooplankton as revealed from fatty acid-carbon stable isotope analyses. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 518: 31-50.

- Eisner, L., Yasumiishi, E. 2017. Large zooplankton abundance as an indicator of pollock recruitment to age-1 and age-3 in the southeastern Bering Sea. Pps. 145-148, In Siddon, E., & Zador, S. Ecosystem Considerations: Status of the Eastern Bering Sea Marine Ecosystem. North Pacific Fishery Management Council, Anchorage, AK.

- Farley, Jr., E.V., Heintz, R.A., Andrews, A.G., Hurst, T.P. 2016. Size, diet, and condition of age-o Pacific cod (Gadus macrocephalus) during warm and cold climate states in the eastern Bering Sea. Deep-Sea Res. Part II 134: 247–254.

- Hermann, A.J., Gibson, G.A., Bond, N.A., et al. 2016. Projected future biophysical states of the Bering Sea. Deep-Sea Res. II 134: 30-47.

Contacts for further Information

George L. Hunt, Jr., University of Washington

Geohunt2 [at] uw.edu

Lisa Eisner, NOAA Alaska Fishery Science Center, Auke Bay Laboratory

Lisa.Eisner [at] NOAA.gov

Neysa M. Call, National Science Foundation

ncall [at] nsf.gov

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| aa013_july_2018_commercial_fisheries.pdf1.5 MB | 1.5 MB |