By: Michael Koskey and Yoko Kugo, Center for Cross-Cultural Studies, Indigenous Studies Graduate Programs, University of Alaska Fairbanks

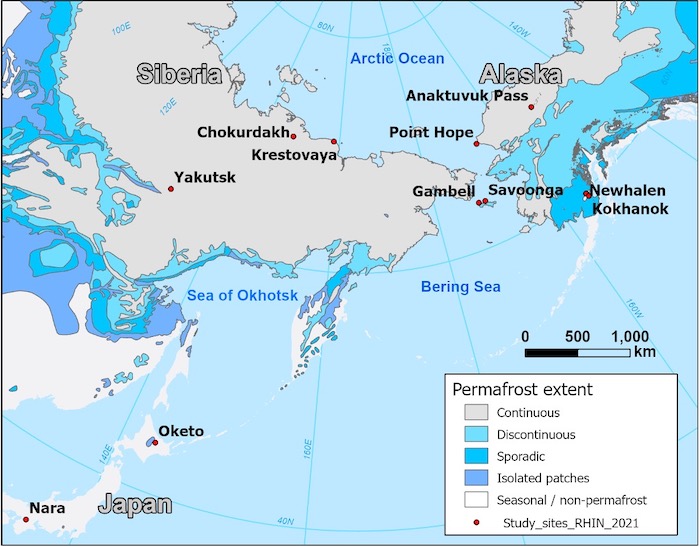

Indigenous peoples in the Arctic and sub-Arctic have used underground cold storage chambers and pits to preserve and share locally harvested food and maintain their lifeways. Our project, Changes in Underground Food Storage Traditions: Exploring Food Life-History and Food Security in Beringian Communities, funded by the National Science Foundation's (NSF) Arctic Social Sciences Program, focuses on the use of underground food storage traditions and practices that have changed due to rapid environmental fluctuations—such as permafrost thawing and moisture conditions—and the arrival of modern education, technologies, and economies. Our project members include social and natural scientists from Alaska, Japan, and Siberia, as well as the partnering communities of Anaqtuuvak (Anaktuvuk Pass), Tikiġaq (Point Hope), Sivungaq (Savoonga), and Sivuqaq (Gambell), shown on the map (Figure 1). Using a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach, these partner communities and researchers are investigating how local capacity to adapt to sociocultural and ecological shifts is effectively applied in terms of resilience and well-being. Our goals are to provide each community a comprehensive record of food life-history for those foods stored in the underground caches in the community in the past to the present; and to develop food security plans and strategies with communities in reaction to recent sociocultural and ecological environmental changes. Some comparative research has been conducted in Siberian communities, which was funded by the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature (RIHN) in Kyoto, Japan from 2020 to 2023. In this article, we would like to acknowledge the generosity of the Tikiġaqmiut (Tikiġaq) for sharing their time, food, and festival with us as outsiders, as well as the generosity of the Nunamiut (Anaqtuuvak) and the Yuit (Sivungaq and Sivuqaq).

As social scientists, when we conducted ethnographic fieldwork with our partnering communities in Anaqtuuvak, Tikiġaq, Sivungaq, and Sivuqaq in 2021 and 2022, we recognized that our roles as participant observers were slightly different because of our identities. Yoko Kugo noted that her identity as a Japanese female born in Tokyo might have eased her ability to connect and establish rapport with Alaska Native people for several reasons: (1) she speaks English as her second language, like many Alaska Native Elders who speak their Native languages as their first language: (2) she likes eating fish and rice as many Alaska Native peoples do; and (3) her Japanese hair, skin, and eye color are similar to those of many Alaska Native people. For Michael Koskey, as a middle-aged, white, American man, it was important to break down the stereotypes of this appearance. Without this, he notes, he would be greatly hampered in communication and trust-building due to the conditions and legacies of colonization.

In 2022, we came to understand that our identities could help in learning insider perspectives about the distribution of whale meat during Qagruq (Whale Festival) in Tikiġaq (Point Hope). We had learned from previous research about Tikiġaq whaling activities that the whaling captain, his wife, and the captain's crew work together in preparation for hunting, harpooning the whale, and butchering and sharing the whale meat with community members. On day three of Qagruq, women cook their traditional food in women's tents while men eat and tell stories at the men's site.

I (Kugo) met a Japanese man who visits his adoptive Iñupiaq family in Tikiġaq every spring. He introduced me to a whaling captain's wife, who allowed me to participate in the women's cooking tent. The whaling captain's wife saw me and immediately asked if I knew how to use an uluaq. Answering, "Yes!" she gave me the uluaq and plastic gloves, and her daughter-in-law showed me how to cut whale intestines in their tent (Figure 2). During that time, I chatted with them, observed their daughter-mother relationship, learned how to cut, clean, and cook whale intestines, and observed how they distribute food to others.

Participating in the whaling captain's wife's tent helped Kugo gain a sense of the tradition of sharing whale meat as the whaling captain's wife guided young women to cut and prepare the meat according to custom. Showing respect in the processing and preparation of meat strengthens the reciprocal relationship between the whale and the Tikiġaqmiut.

In the men's area, food was brought by women and children for distribution to the men. This area was separated from the women's area by a row of whale boats, which were also used as windbreaks. Here the men discussed everything from daily life to shared events (usually humorous or harrowing), as well as talked about certain aspects of the whale hunt, preparation for Qagruq, and the reasons and meanings for the festival, and joked about everything. This humor greatly lightened the mood, and made it easier to learn and remember the knowledge being shared.

Due to my (Michael Koskey) presence as a middle-aged, white, American man, there were descriptions of the equipment and processes of the whale hunt, as well as some discussion of related proper behaviors. The Tikiġaqmiut were generous and gracious throughout Qagruq, and I was able to learn much about whale hunting, Qagruq, and its importance in defining and reinforcing local worldview and ethics, and local cultural behavioral expectations, as well as protocols for the proper distribution of a whale (Figure 3).

Most importantly in this project is the continuous and frequent interaction with community members and leaders, and this effort is led by Kugo, including ongoing negotiations regarding the nature and conduct of the project itself. This includes issues of access (permissions) for talking with Knowledge-bearers, accessing places for permafrost analysis and measurement of subsidence. We also discussed the effects of these changes on the community regarding topics from food security to structural integrity of subterranean storage pits and their ongoing effectiveness at preserving meat (fermentation and freezing). Working together—with diversity in terms of ethnic and national identity, academic disciplines, and gender as an inherent part of a research team—enables a more multifaceted approach to sociocultural studies. At once cross-cultural, international, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, and inter- and trans-disciplinary, the co-investigators of this project also work with local community researchers who are critical to the successful and respectful conduct of this project. Together we seek to identify the factors related to climate change and the global economy that threaten the continuing practice of traditional lifeways regarding the harvesting, preservation, preparation, and consumption of local foods.

About the Authors

Yoko Kugo is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Center for Cross-Cultural Studies, Indigenous Studies Graduate Program at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Her interests include Alaska Native cultures and lifeways, oral history, Indigenous place names and stories of the places (ethnogeography), Traditional and Indigenous Knowledge, and histories of Japanese pioneers in the Arctic during the Yukon gold rush.

Yoko Kugo is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Center for Cross-Cultural Studies, Indigenous Studies Graduate Program at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Her interests include Alaska Native cultures and lifeways, oral history, Indigenous place names and stories of the places (ethnogeography), Traditional and Indigenous Knowledge, and histories of Japanese pioneers in the Arctic during the Yukon gold rush.

Michael Koskey is an Associate Professor with the Center for Cross-Cultural Studies, which offers a Master's of Arts and a PhD in Indigenous Studies, at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Mike's research focuses on oral history, Traditional Knowledge, food sovereignty and security, ethnohistory, culture change, decolonization, resource use and allocation, and Indigenous cosmologies/mythologies.