By: Axel J. Schweiger, University of Washington Applied Physics Laboratory (UW/APL); Michael Steele, UW/APL; Jinlun Zhang, UW/APL; G. W. K. Moore, University of Toronto; and Kristin L. Laidre, UW/APL.

In August 2020, as the German Icebreaker Polarstern transited northward as part of the MOSAiC expedition, it followed a route across the Wandel Sea north of Greenland. This area is normally marked by compact, thick multiyear ice created by cold temperatures and onshore winds and currents that stretches from the Wandel Sea southwestward along the northern coast of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. This region has been predicted to retain multiyear ice much longer than elsewhere as the climate warms, and is therefore referred to as the “Last Ice Area” (LIA). In fact, predictions of when sea ice-free summers in the Arctic will occur usually assume an area threshold of one million square kilometers, a number that implicitly accounts for the LIA. The LIA is considered to be a last refuge for ice-associated Arctic marine mammals, such as polar bears (Ursus maritimus), ice-dependent seals such as ringed seals (Pusa hispida) and bearded seals (Erignathus barbatus), and walrus (Odobendus rosmarus) throughout the 21st century. The LIA is also important for ivory gulls that breed in north Greenland.

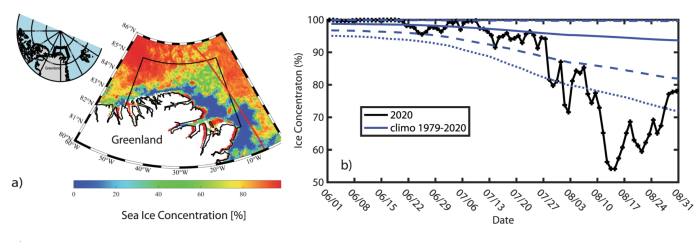

We used satellite data and the PIOMAS coupled sea ice-ocean model to diagnose the mechanisms responsible for the summer 2020 record minimum and to put them into historical context. Our focus was on the Wandel Sea in the eastern LIA, although the implications of this study may be relevant to the entire LIA region. We performed an historical simulation using PIOMAS over the years 1979-2020; we also ran a sensitivity study in which summer 2020 meteorological forcing was fixed, but an ensemble of past year’s ice and ocean conditions on June 1 were used as initial conditions.

This study showed that climate-changed associated thinning of Wandel Sea sea ice had an approximately 20% impact on total sea ice loss by the end of summer 2020, with the most notable effect in early summer. Thinner sea ice, even in the LIA, is more vulnerable to summer forces that act to reduce ice volume, for example it responded more quickly to winds that swept the ice out of the Wandel Sea. It also allowed more sunlight to penetrate into the upper ocean; this heat eventually mixed up and melted ice from the bottom in addition to the usual atmospheric melting on top of floe surfaces. Another way to say this is that we are seeing a strong ice-albedo feedback in the traditionally icy LIA, something that was quite unexpected.

In fact, 1 June 2020 ice conditions were a bit thicker than in recent years, owing to convergence over the winter of 2019/2020. Nonetheless, this didn’t matter—ice still reduced to an historical minimum by August 2020. This happened because while there was some thick ice, there was also a lot of thin ice, with a thickness distribution that was highly non-Gaussian (i.e., non-bell-shaped).

A climate impact of 20% may not sound like a lot, but in fact it is a typical magnitude for climate change-induced forcing. For example, this is about the same percent contribution as was found for the global warming impact on Superstorm Sandy.

We also ran a second sensitivity study in which 1 June 2020 ice and ocean conditions were fixed, but an ensemble of past year’s meteorological data were imposed. This study showed that internal climate variability (i.e., weather) was responsible for approximately 80% of sea ice loss in summer 2020, especially toward the end, in August. Specifically, there was a strong and very large anticyclonic high-pressure cell that covered much of the Arctic Ocean in late summer which swept ice southwestward out of the Wandel Sea and along the northern coast of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago and into the Beaufort Sea. New research indicates that this continued over the following winter 2020/2021, leading to unusually thick ice in the Beaufort Sea in summer 2021. We also found that recent years (2018 and 2019) had sufficiently thin ice so that if the winds of 2020 were imposed, record low sea ice would have resulted. The idea here is that the “new Arctic” state in the Wandel Sea (and perhaps in the LIA as a whole) is more vulnerable to wind anomalies than previously thought.

With continued thinning, more frequent low summer sea ice events are expected. We suggest that the Last Ice Area, an important refuge for ice-dependent species, is less resilient to warming than previously thought.

The research was funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation, NASA, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada; the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; the Office of Naval Research; and the World Wildlife Fund Canada.

References

Schweiger, A.J., Steele, M., Zhang, J. et al. Accelerated sea ice loss in the Wandel Sea points to a change in the Arctic’s Last Ice Area. Commun Earth Environ 2, 122 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00197-5

About the Authors

Axel Schweiger is the current chair of the Polar Science Center. His research focuses on sea ice, clouds and radiation in the Arctic. He is using satellite data, models and in-situ observations to improve our understanding of sea ice and cloud variability. He has developed the PSC Arctic Ice Volume Page which provides monthly updated total Arctic Ice Volume estimates based on the PIOMAS model. He has worked on the validation, improvements, and applications of PIOMAS to a variety of problems.

Michael Steele is interested in the large-scale circulation of sea ice and water in the Arctic Ocean. He uses both observed data and numerical model simulations to better understand the average circulation pathways as well as the causes of interannual variations in these pathways.

Jinlun Zhang is interested in quantifying and understanding climate change in the Polar Regions. He investigates the properties of polar ice-ocean systems by developing large-scale sea ice and ocean models such as the Pan-arctic Ice-Ocean Modeling and Assimilation System (PIOMAS). He has developed efficient sea ice dynamics models that are particularly useful for stable, high-resolution modeling.

G. W. Kent Moore uses theoretical, computational and observational techniques to improve our knowledge of the dynamics of the climate system so as to improve our ability to place currently observed changes to the climate in a long-term context. Professor Moore also applies these same techniques to the study of the meteorology of mountainous areas of the Earth as well as the impact that weather in these areas has on human physiology and performance. Professor Moore undertakes field work in the Arctic, Greenland and the Himalaya using automatic weather stations, instrumented research aircraft and ships in the course of his research.

Kristin Laidre working on problems of applied animal ecology. Her research is field-based, largely empirical, and focuses on using quantitative data on individual movements, foraging behavior, and life history of Arctic top predators to understand population dynamics, and the uniting aspects of behavioral, population, and evolutionary ecology. She is particularly interested in linking individual performance to an animal’s selection for habitat resources and predicting how these relationships will be impacted by climate change.