By: Melissa K. Ward Jones, University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF); Benjamin M. Jones, UAF, Glenna Gannon, UAF; Tobias Schwoerer, UAF; Mikhail Kanevskiy, UAF; Jill Russell, Boreal Peonies; Dave Russell, Boreal Peonies; and Iris Sutton, Ice Wedge Art and Farm

We acknowledge our research takes place on the traditional homelands of the Lower Tanana Dene, Chena Athabascan, Inupiaq, Yup'ik, and Sakha (Yakut) peoples.

Polar Peonies, LLC, located in Fairbanks, was the first commercial peony farm in Alaska. The field was cleared in 2001 and peonies were planted in 2002. The owners took pride in cultivating on permafrost-affected soils, however, starting around 2014, the land surface began to dip, and sinkholes began to appear, causing some peony plants to die. Now, the peonies have been moved to a new field and the original was abandoned in 2019 (Figure 1). What happened at Polar Peonies' farm is an example of permafrost degradation that can happen in agricultural fields containing ice-rich permafrost (Figures 1–3). These agricultural fields can experience topographic changes and land surface subsidence (Figure 3, bottom) as a result of permafrost thaw that occurs after land clearing removes the protective vegetation layer. Widespread, near-surface permafrost degradation has been observed in recent decades (e.g., Nitze et al., 2018), driving cascading biophysical changes that affect Arctic ecosystems, communities, and economies, including agriculture (Desyatkin et al., 2021). Like Polar Peonies, permafrost degradation causing land surface subsidence from melting ground ice (Figure 3, bottom) can drive farmers to abandon their fields (Rockie 1942; Pewe 1954).

The history of farming in permafrost regions of the Circumpolar North varies. For thousands of years, 20 different Indigenous Arctic peoples from Eurasia have herded semi-domesticated reindeer over vast distances (Magga et al., 2009). The Tlingit and Haida people cultivated potatoes as far north as southeast Alaska (Zhang et al., 2009). Within Europe and Siberia, conventional farming began in the 1600s (Poeplau et al., 2019; Desyatkin et al., 2021). By contrast, in North America, farming activities increased in the late 1800s through the northern influx of trappers, traders (Robinson 2010), and later by miners during the Gold Rush era (Miller 1951). In response to the population boom in Alaska, US Agriculture Agent, Charles C. Georgeson was tasked by Congress in 1898 to determine if Alaska had any agriculture and horticulture development potential. Tackling every challenge with optimism and enthusiasm, Georgeson was unperturbed by skeptics, including miners who, "looked on me and my mission with pity and derision" at his desire to grow strawberries in Sitka. He succeeded at developing a hybrid variety in seven years that was later planted around the state, including Fairbanks (Figure 3 top; UAF AFES, 1998, p. 26). Georgeson was a forward-thinker who established experimental stations and an agricultural research program in Alaska that continues today.

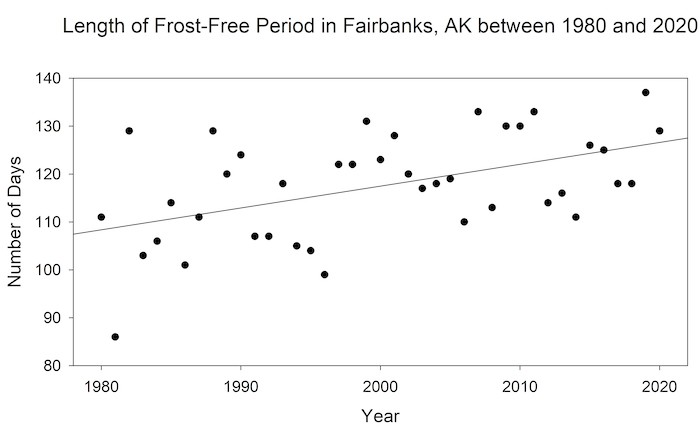

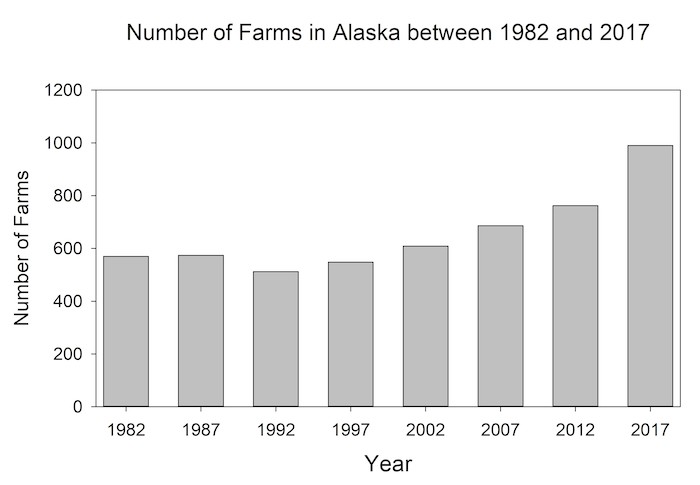

Since the research efforts of Georgeson, northern high latitude areas are expected to become the next agricultural frontier due to climate warming that is driving an increase in summer air temperatures and growing season length (Figure 4). Hannah et al. (2020) predict that boreal regions of the Northern Hemisphere and mountainous areas will see the greatest increases in suitable land area for growing globally important crops resulting from climate-driven warming under both RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5 scenarios by 2060–2080. Most predicted areas within the new agriculture frontier also contain permafrost, and we define these systems as permafrost-agroecosystems. Already, in the US, the number of new farms and farmers coming to Alaska has been increasing since 1992 (Figure 5) and while new farms in Alaska increased by 30% between 2012 and 2017, there was a 3.2% decline during the same period in the contiguous US (USDA, NASS, 2019). For the ongoing agricultural expansion to be successful and solution-oriented, its development needs to account for variability in permafrost conditions, the complexity of existing social-ecological systems in the Arctic, and needs to include Arctic resident farmers in research efforts.

Note: Data in Figure 5 is accessed at the USDA National Agriculture Statistics Service.

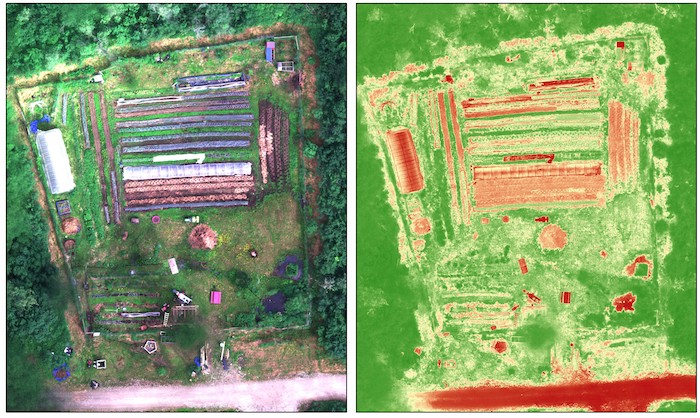

Our new project, Permafrost Grown, is a five-year, $3 million transdisciplinary project funded by the National Science Foundation's Navigating the New Arctic program and is studying the interactions and feedbacks within permafrost-agroecosystems by co-producing knowledge with Alaskan and Siberian farmers. To better understand permafrost-agroecosystems, Permafrost Grown is using a combination of a sensor-based observational data network; characterizing permafrost using boreholes and geophysics; testing permafrost mitigation strategies using on-farm agricultural experiments; using dendrogeomorphology to time permafrost thaw using leaning trees; and using unmanned arial vehicle (UAV) based remote sensing to monitor plant health throughout the growing season (Figure 6), as well as to monitor ground surface subsidence and snow depth. We are focusing on in-the-ground farming to directly assess the interactions and feedbacks within permafrost-agroecosystems and are planning to study several farm sites in the Tanana Valley near Fairbanks, Alaska and one in Bethel, Alaska that either grow vegetables, peonies, and/or raise livestock (Figure 7). Moreover, we are interested in the legacy impacts of land cleared 100 to 300 years ago that was initially used for agriculture but has since been either abandoned or converted to a different land use with sites, including a golf course, a satellite downlink facility, and a migratory waterfowl refuge. Furthermore, we are collaborating with the Melnikov Permafrost Institute based in Yakutsk, Russia, to conduct a knowledge exchange with Siberian farmers and researchers.

Permafrost Grown will also evaluate the socioeconomic trade-offs of intensifying permafrost-agroecosystems that will contribute to the development of decision-making tools for farmers through planned outputs including best practice guides, and guides with mitigation strategies for agriculture activities in permafrost-affected soils. Planned outreach and educational activities will engage both farmers and the public to raise awareness of permafrost-agroecosystems. These activities include annual workshops and "Permafrost Grown" days at the Fairbanks Farmer's Market, new interpretative signage in Fairbanks, as well as establishing the first UAF Toolik Field Station Community Garden and supporting the Family Farmers Program in Anaktuvuk Pass created and run by Gardens in the Arctic.

An improved understanding of the permafrost-agroecosystem as a coupled social-ecological system will help guide sustainable and adaptable cultivation and development practices. Moreover, understanding the impacts of permafrost-cultivation feedbacks on agricultural systems benefits high-latitude communities by improving food security and economic resiliency.

References

University of Alaska Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station. (UAF AFES, 1998). Agroborealis, 30 (1); Catalogue #30-1.

Hannah, L., Roehrdanz, P.R., KC, K.B., Fraser, E.D., Donatti, C.I., Saenz, L., Wright, T.M., Hijmans, R.J., Mulligan, M., Berg, A. and van Soesbergen, A. 2020. The Environmental Consequences of Climate-driven Agricultural Frontiers. PloS One, 15(2), p.e0228305.

Magga, O.H., Mathiesen, S.D., Corell, R.W. and Oskal, A. 2009. Reindeer Herding, Traditional Knowledge, Adaptation to Climate Change and Loss of Grazing Land. IPY EALÁT Project Executive Summary Report, Arctic Council Sustainable Development working Group. 7th Arctic Council Ministerial Meeting, Nuuk, Greenland.

Miller, E.W. 1951. Agricultural Developments in Interior Alaska. The Scientific Monthly, 73(4), 245–254.

Nitze, I., G. Grosse, B. M. Jones, V. Romanovsky, and J. Boike. 2018. Remote Sensing Quantifies Recent Permafrost Region Disturbances Across the Arctic and Subarctic. Nature Communications 9: 5423, doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07663-3

Péwé, T.L. 1954. Effect of Permafrost on Cultivated Fields, Fairbanks area, Alaska (No. 989). US Government Printing Office.

Poeplau, C., Schroeder, J., Gregorich, E., and Kurganova, I. 2019. Farmers' Perspective on Agriculture and Environmental Change in the Circumpolar North of Europe and America. Land 8(12), 190.

Rockie, W. A. 1942. Pitting on Alaskan Farmlands: A New Erosion Problem. Geographical Review 32(1), 128-134.

US Department of Agriculture, National Agriculture Statistics Service (USDA, NASS, 2019). https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2017/index.php

Zhang, L., Brown, C.R., Culley, D., Baker, B., Kunibe, E., Denney, H., Smith, C., Ward, N., Beavert, T., Coburn, J. and Pavek, J.J. 2010. Inferred Origin of Several Native American Potatoes from the Pacific Northwest and Southeast Alaska Using SSR Markers. Euphytica, 174(1), pp.15–29.

About the Authors

Melissa K. Ward Jones (UAF) – Melissa Ward Jones is a permafrost geomorphologist and a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Institute of Northern Engineering at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and is leading the Permafrost Grown project. She is interested in the causes, consequences, and significance of geomorphic change and applying her knowledge of permafrost to sustainability issues. She has conducted fieldwork on Axel Heiberg and Ellesmere Islands, Canada, Svalbard, Norway, and throughout Alaska, USA.

Melissa K. Ward Jones (UAF) – Melissa Ward Jones is a permafrost geomorphologist and a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Institute of Northern Engineering at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and is leading the Permafrost Grown project. She is interested in the causes, consequences, and significance of geomorphic change and applying her knowledge of permafrost to sustainability issues. She has conducted fieldwork on Axel Heiberg and Ellesmere Islands, Canada, Svalbard, Norway, and throughout Alaska, USA.

Benjamin M. Jones (UAF) – Benjamin M. Jones is a Research Professor in the Institute of Northern Engineering at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. His research focuses on Arctic and sub-Arctic systems and combines the use of GIS and remote sensing techniques with field observations and laboratory analyses to better understand the causes and consequences of landscape change, processes, and feedbacks in northern high-latitude environments across a multitude of spatial and temporal scales. For the Permafrost Grown project, he will work with farmers on environmental sensor observation network development and deployment, multi-season remote sensing with UAVs, and assessing landscape changes using historical remote sensing datasets.

Benjamin M. Jones (UAF) – Benjamin M. Jones is a Research Professor in the Institute of Northern Engineering at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. His research focuses on Arctic and sub-Arctic systems and combines the use of GIS and remote sensing techniques with field observations and laboratory analyses to better understand the causes and consequences of landscape change, processes, and feedbacks in northern high-latitude environments across a multitude of spatial and temporal scales. For the Permafrost Grown project, he will work with farmers on environmental sensor observation network development and deployment, multi-season remote sensing with UAVs, and assessing landscape changes using historical remote sensing datasets.

Tobias Schwoerer (UAF) – Tobias Schwoerer is a Research Assistant Professor of Natural Resource Economics in the International Arctic Research Center. His work centers around the human dimensions of sustainability where he is most interested in actionable research that informs public policy and private decision making. For the Permafrost Grown Project, he will work with partner farmers to illuminate trade-offs related to permafrost mitigation and come up with co-produced decision support tools.

Tobias Schwoerer (UAF) – Tobias Schwoerer is a Research Assistant Professor of Natural Resource Economics in the International Arctic Research Center. His work centers around the human dimensions of sustainability where he is most interested in actionable research that informs public policy and private decision making. For the Permafrost Grown Project, he will work with partner farmers to illuminate trade-offs related to permafrost mitigation and come up with co-produced decision support tools.

Mikhail Kanevskiy (UAF) – Mikhail Kanevskiy is a Research Assistant Professor in the Institute of Northern Engineering at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. He studies structure and properties of permafrost, permafrost-related geological hazards, and engineering and environmental problems in the areas of ice-rich permafrost. He has performed fieldwork in various parts of Siberia, Alaska, and northern Canada.

Mikhail Kanevskiy (UAF) – Mikhail Kanevskiy is a Research Assistant Professor in the Institute of Northern Engineering at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. He studies structure and properties of permafrost, permafrost-related geological hazards, and engineering and environmental problems in the areas of ice-rich permafrost. He has performed fieldwork in various parts of Siberia, Alaska, and northern Canada.

Glenna Gannon (UAF) - Glenna Gannon is a Research and Extension Assistant Professor of Sustainable Food Systems in the Institute of Agriculture, Natural Resources, and Extension. Her work focuses on the sustainable development of high-latitude food production and human dimensions of northern food systems. For the Permafrost Grown project, she will work with partner-producers to develop on-farm agricultural experiments aimed at answering permafrost-related questions and develop education and outreach materials based on research findings.

Glenna Gannon (UAF) - Glenna Gannon is a Research and Extension Assistant Professor of Sustainable Food Systems in the Institute of Agriculture, Natural Resources, and Extension. Her work focuses on the sustainable development of high-latitude food production and human dimensions of northern food systems. For the Permafrost Grown project, she will work with partner-producers to develop on-farm agricultural experiments aimed at answering permafrost-related questions and develop education and outreach materials based on research findings.

Jill and Dave Russell (Boreal Peonies) - Jill and Dave Russell are the owners of Boreal Peonies, a family run, 40-acre peonies farm established in 2012 in Two Rivers, Alaska. The farm serves both as a scientific research station that serves the Alaska Peonies Growers Association and the Alaska peonies industry, and sells large cut peonies flowers to florists and wholesalers worldwide. In the off season, Jill and Dave are Teaching Professors at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio.

Jill and Dave Russell (Boreal Peonies) - Jill and Dave Russell are the owners of Boreal Peonies, a family run, 40-acre peonies farm established in 2012 in Two Rivers, Alaska. The farm serves both as a scientific research station that serves the Alaska Peonies Growers Association and the Alaska peonies industry, and sells large cut peonies flowers to florists and wholesalers worldwide. In the off season, Jill and Dave are Teaching Professors at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio.

Iris Sutton (Ice Wedge Art and Farm) - Iris Sutton is the owner of Ice Wedge Art and Farm, established in 2012 and is located in Fairbanks, AK. The farm grows vegetables, raises goats and chickens. Iris grew up both in rural and urban Alaska and enjoys the outdoors, an inspiration for her artwork that explores Alaska’s unique wildlife and landscapes.

Iris Sutton (Ice Wedge Art and Farm) - Iris Sutton is the owner of Ice Wedge Art and Farm, established in 2012 and is located in Fairbanks, AK. The farm grows vegetables, raises goats and chickens. Iris grew up both in rural and urban Alaska and enjoys the outdoors, an inspiration for her artwork that explores Alaska’s unique wildlife and landscapes.