By: Mark Goldner, Science Teacher at Heath K-8 Elementary School in Brookline, Massachusetts

Growing up as a suburban kid near Boston, I never imagined spending a summer doing Arctic field research. But here I am, having been lucky enough to spend two summers with Dr. Julie Brigham-Grette (UMASS Amherst) studying the effects of climate change on the meltwater plumes of glacier systems in Kongsfjord, Svalbard at 79°N latitude.

My first research experience with Dr. Brigham-Grette was as a PolarTREC teacher in 2011. That summer, our group, co-led by Dr. Brigham-Grette and Dr. Ross Powell (NIU) and funded by the National Science Foundation, included a variety of oceanography measurements and sediment coring and collection methods.

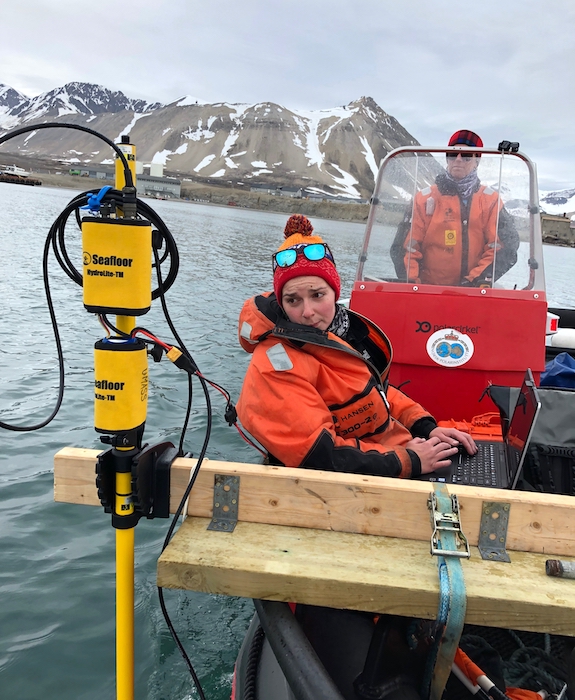

In July 2021, our team included Dr. Brigham-Grette and two students—PhD candidate, Kelly Mckeon (Woods Hole/MIT) and undergraduate, Xander Kirshen (UMASS Amherst). Funded by the National Geographic Explorers Program, we spent three weeks collecting oceanography and bathymetry data, along with drone video to better understand the dynamics of the glacier meltwater system and to document the dramatic effects that climate change is having on these magnificent Svalbard glaciers. My participation was funded by grants from the Brookline Education Foundation and the National Education Association, and PolarTREC graciously allowed me to use their blogging platform and provided support for a live Zoom presentation while we were in the field.

By the end of the school year this past June, consumed with the seemingly impossible challenges that came with pandemic teaching, I was completely exhausted. With almost no break, we were off to the Arctic a few days later. We had a ten-day COVID quarantine in Oslo, Norway, then flew up to Longyearbyen in Svalbard, and finally traveled to Ny Ålesund, an international research station, which can hold up to around 150 scientists.

Despite my exhaustion from the year, and as intense as the field work was, I came out of the experience totally rejuvenated! What a treat for me to be entirely immersed in science for almost a month—and under the tutelage of the amazing Dr. Brigham-Grette. I have learned so much from Julie over the past ten years, from her deep knowledge about glacial geology to her extensive field experiences.

While in the midst of the mundane process of data collection, I was reminded of how messy and unpredictable field work can be. Whether it was as serious as spending days trying to get the bathymetry setup working properly, as uncomfortable as dressing improperly for a long, cold, and rainy day out on the fjord, or as silly as being attacked by the local terns, nothing ever quite goes along as planned. Flexibility and patience are essential traits to bring to the work.

Dr. Brigham-Grette plans to compile the data we collected this summer and add it to the growing body of data she has amassed over the past two decades (having first studied this area in 1995), along with data collected by other researchers in the area. Studying the sub-glacial "plumbing system" is important to understanding how glaciers are responding, not just to a warming atmosphere, but to a warming ocean.

An important aspect of our work this summer was to collect drone video footage along and above the glacier face. Getting that close to the glacier helps us gain insight into how sediment plumes behave as they exit the glacier. In addition, having this footage provides dramatic visual imagery that can be used to share with the general public as we communicate about the effects of the climate crisis.

Flying the drone was a wonderful (if at times, slightly hair-raising) experience as I was able to take what were essentially virtual tours of these amazing glaciers. It also gave me the opportunity to document features of recently de-glaciated areas, which I plan to use in my own teaching of the glacial history of New England.

Being able to do a research project like this is, for many teachers, an experience of a lifetime. But I was able to return and participate twice! One of the important aspects of my return was my first-hand witness to the devastating retreat of the glaciers. I was able to document the ten-year retreat of over 1.7km of the faces of the Kronebreen and Kongsvegen Glaciers as well as the thinning of these glaciers.

I have a responsibility to make topics like climate change and geology accessible to young people. My field experiences bring these topics alive for my students. Having had these field research experiences, my students see me not just as a science teacher, but as a bona fide scientist in my own right. I can talk confidently about the process of science. When I show them images of glacial retreat, they are from my own first-hand account (not just a picture found on a web image search) brought alive further by my own emotional response. I think this has enormous intangible results in terms of students' heightened enthusiasm for, and interest in, science.

Giving students a flavor of the actual field work is also important to me. Following my 2011 experience, every year I have my students do their own sediment coring at a local pond to see if we can detect any evidence of climate change. This year I will also bring in some of our recent CTD data as part of a data visualization exercise.

Ideally, science instruction should be a hands-on, immersive experience. What better way to impart our enthusiasm for authentic instruction than to participate in hands-on immersive field experiences ourselves!

For more information, see:

- Mark Goldner's PolarTREC blog from this summer's research field work

- Video clips of drone footage and other video clips from the summer field work

- Sediment Coring Activities

About the Author

Mark Goldner teaches 7th and 8th grade science at the Heath K-8 Elementary School in Brookline, Massachusetts, and he has been teaching middle and high school science for the past 29 years. He has led extensive professional development work for teachers around science and literacy, and is co-author of the book, "The Stories of Science." Mark has participated in multiple polar research experiences through PolarTREC, Alaska Geographic, the Canadian Wildlife Federation, and the ARMADA project.

Mark Goldner teaches 7th and 8th grade science at the Heath K-8 Elementary School in Brookline, Massachusetts, and he has been teaching middle and high school science for the past 29 years. He has led extensive professional development work for teachers around science and literacy, and is co-author of the book, "The Stories of Science." Mark has participated in multiple polar research experiences through PolarTREC, Alaska Geographic, the Canadian Wildlife Federation, and the ARMADA project.