By: David Kadko, 2015 Expedition Chief Scientist, Professor and Associate Director Applied Research Center, Florida International University; William Landing, Co-Chief Scientist, Professor Florida State University; Ignatius Rigor, Applied Physics Laboratory (APL); Wendy Ermold, APL; Bill Schmoker; PolarTREC teacher; David Forcucci, U.S. Coast Guard Science Coordinator.

In 2015 a team of environmental scientists boarded the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Healy and sailed north into the Arctic Ocean to take part in an international GEOTRACES program investigating the cycling of trace elements and their isotopes, an important indicator for ocean health and contamination. During this voyage, the U.S. Arctic GEOTRACES program participated in a novel outreach project, "Float Your Boat", to involve students and the public with an Arctic research expedition. The program was coordinated with Dave Forcucci, U.S. Coast Guard Marine Science Coordinator.

With funding from the National Science Foundation, over 1,000 8-inch (20-cm) long cedar boats were commissioned from the Center for Wooden Boats in Seattle, Washington and distributed to school groups, scout troops, and science open house events around the country. Students personalized their boats with bright colors and upon return to Seattle, the surface of each boat was stamped prominently with the program's website before being packed into the hold of the USCGC Healy for the journey to the North Pole. During the GEOTRACES cruise, the small boats, packed in cardboard boxes, were deployed on ice floes between 87.5N and 80N on the 150W meridian. After drifting with the Arctic ice, it was hoped that the boats would eventually be freed from its grasp, the cardboard boxes would disintegrate, and the small boats would float to a distant shore to be discovered and reported. This project has a Facebook page and is described by our PolarTREC supported teacher-at-sea, Bill Schmoker in his journal.

Each floe was tagged with a satellite buoy deployed for the University of Washington Applied Physics Laboratory for their real-time tracking of ice movement by the International Arctic Buoy Programme. As it turned out, the iridium satellite-linked buoys provided an opportunistic chance for understanding the movement of the boats for about a year and a half. This provided an unexpected synergy between educational outreach and scientific investigation.

In October 2018, three years after deployment, one of the small wooden boats was found by Bolli Thor, a gentleman in Iceland. He wrote, "These are the coordinates 63.962285, -22.734055 where I found one of your little wooden boats, near the small town called Sandgerði in Iceland where I live. I found it at my favorite spot, where I usually walk with my dog called Tyra." The recovered weathered boat is shown in Figures 1 and 2. Remarkably, we identified the pre-deployment picture, the student, and school.

Later, on 16 April 2019, another boat was found by Guðmundur Örn Benediktsson, who wrote, "Greetings from Kópasker, Iceland. Hello! One of your floatboats was found at Harðbaksvík, NE Iceland, April the 16th 2019; co-ordinates very close to 66.5150 N and 15.994040 W." (Figure 3). He is a teacher in Kópasker and involved in collecting plastics on his native shore as a means of bringing attention to this worldwide pollution problem.

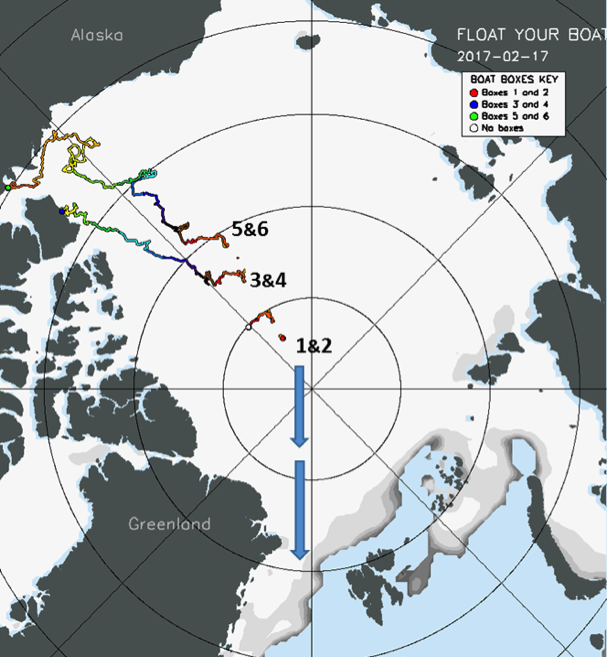

These discoveries prompted us to investigate how these small boats could have gotten to Iceland from their point of deployment. The satellite drift track data from the US Arctic GEOTRACES small boat deployments stopped in February 2017 (Figure 4). Four groups of boats (boxes 3, 4, 5, and 6) were on floes that ran aground in northern Canada, while two groups (boxes 1 and 2) that were deployed near the North Pole were entrained in the Arctic Ocean's Transpolar Drift, which exits the Arctic Basin by its only deep-water channel through Fram Strait and traveled into the East Greenland Current (a buoy deployed in April near the North Pole has a high probability of following that general route to reach the central Greenland Sea by the following mid-winter).

The dual purposes of the "Float Your Boat" project, a happy marriage of science outreach and investigation, allowed researchers to simultaneously generate excitement for their work and study the Arctic using unorthodox tools. Furthermore, the project transcended international boundaries, its success relying ultimately upon actions of interested citizens of Iceland.

William Landing (Co-Chief Scientist) said these kind of projects—and the astonishing, serendipitous stories they produce—are crucial in cultivating broad enthusiasm about science among the general public, especially at a time when scientific literacy will be an important tool in addressing the looming specter of environmental catastrophe.

"The 'Float Your Boat' program engaged not only the students who decorated their boats, but also the teachers, scout leaders, and parents who were involved," he said. "There is always a need to reach out to the public and help them understand the value of scientific research, especially these days when humans are having such a large impact on the environment."

For further information, please see the Float Your Boat Project and "The U.S. Arctic GEOTRACES Expedition Set to Embark in 2015" in the spring 2015 issue of Witness the Arctic. Dr. Peter Morton (Florida State University) and Dr. Tim Kenna (Columbia University) contributed to the success of this effort.

About the Authors

David C. Kadko, PhD is a professor and Associate Director of the Applied Research Center at Florida International University. His research interests lie in utilizing naturally occurring radioactivity for tracing the pathways and discovering the rates of various oceanic processes. Because naturally occurring radioisotopes have half-lives ranging from seconds to many years, it is possible to study processes that encompass a great variety of temporal and spatial scales.

David C. Kadko, PhD is a professor and Associate Director of the Applied Research Center at Florida International University. His research interests lie in utilizing naturally occurring radioactivity for tracing the pathways and discovering the rates of various oceanic processes. Because naturally occurring radioisotopes have half-lives ranging from seconds to many years, it is possible to study processes that encompass a great variety of temporal and spatial scales.

William M. Landing, PhD is a professor in the Department of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Science at Florida State University. His research interests include the biogeochemistry of trace elements in marine and fresh waters, the chemistry and deposition of atmospheric aerosols, and mercury cycling in the atmospheric and in aquatic environments.

William M. Landing, PhD is a professor in the Department of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Science at Florida State University. His research interests include the biogeochemistry of trace elements in marine and fresh waters, the chemistry and deposition of atmospheric aerosols, and mercury cycling in the atmospheric and in aquatic environments.

Ignatius Rigor, PhD is a climatologist at the Polar Science Center, Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), and an Affiliate Assistant Professor in the School of Oceanography at the University of Washington (UW) in Seattle. Dr. Rigor studies sea ice, and how it interacts with the atmosphere and ocean. His primary tools for research are observations from drifting buoys and satellites.

Ignatius Rigor, PhD is a climatologist at the Polar Science Center, Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), and an Affiliate Assistant Professor in the School of Oceanography at the University of Washington (UW) in Seattle. Dr. Rigor studies sea ice, and how it interacts with the atmosphere and ocean. His primary tools for research are observations from drifting buoys and satellites.

Wendy Ermold is a scientific programmer and field technician for the Polar Science Center (Applied Physics Laboratory, University of Washington). She joined the Polar Science team in 1998.

Wendy Ermold is a scientific programmer and field technician for the Polar Science Center (Applied Physics Laboratory, University of Washington). She joined the Polar Science team in 1998.

Bill Schmoker is an Earth Science teacher at Centennial Middle School in Boulder, Colorado where he has taught for over 20 years. Mr. Schmoker was a PolarTREC teacher in 2010 and 2015 and a National Geographic Grosvenor Teacher Fellow in 2013. He is passionate about birding and has photographed over 640 species of North American birds. His photos appear internationally in numerous books, magazines, web sites, and interpretive signage.

Bill Schmoker is an Earth Science teacher at Centennial Middle School in Boulder, Colorado where he has taught for over 20 years. Mr. Schmoker was a PolarTREC teacher in 2010 and 2015 and a National Geographic Grosvenor Teacher Fellow in 2013. He is passionate about birding and has photographed over 640 species of North American birds. His photos appear internationally in numerous books, magazines, web sites, and interpretive signage.

David Forcucci has coordinated marine science for the USCGC Healy for almost two decades. He has a MS degree in Marine Biology. Dave enjoys the sea in his free time and is an underwater photographer with the ability to free dive to 40 meters.

David Forcucci has coordinated marine science for the USCGC Healy for almost two decades. He has a MS degree in Marine Biology. Dave enjoys the sea in his free time and is an underwater photographer with the ability to free dive to 40 meters.