By: Emily Osborne, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Arctic Research Program; Jacqueline Richter-Menge, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Institute of Northern Engineering; Martin Jeffries, Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory of the Engineer Research and Development Center, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Arctic Report Card 2018, an interagency and international publication coordinated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), was released on 11 December 2018 during the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting in Washington, D.C. In its 13th year, the peer-reviewed Arctic Report Card (ARC) describes a range of land, ice, and ocean observations made throughout the Arctic. ARC 2018 includes 14 essays written by more than 80 scientists from 12 countries. The collective content of the report makes clear that the continued warming of the Arctic atmosphere and ocean are driving broad change in the environmental system in predicted, and also unexpected, ways.

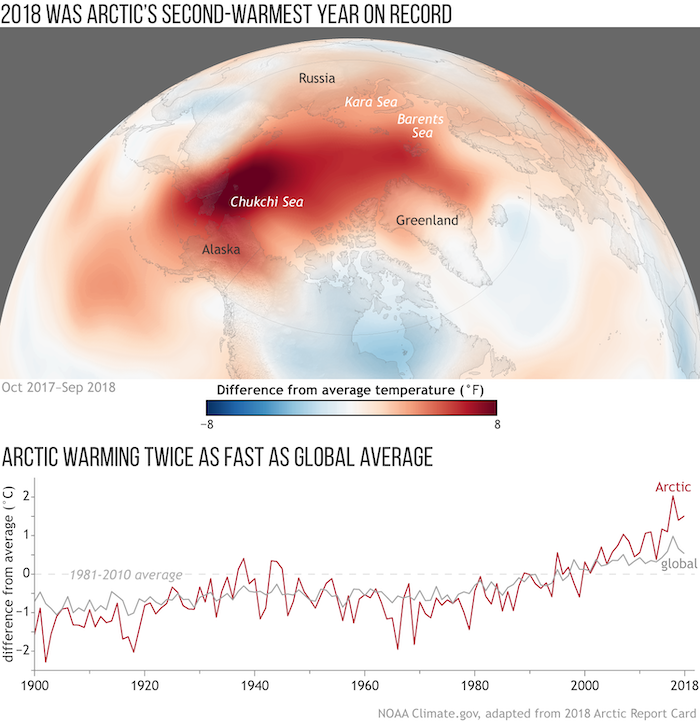

Surface air temperatures in the Arctic continued to warm twice as fast as the global average (see Figure 1). In 2018, the Arctic average annual air temperature was 1.7°C (3.0°F) above the long-term average, making it the second warmest (after 2016) since 1900. Arctic air temperatures for the past five years (2014—2018) have exceeded all previous records since 1900. A slower and wavier jet-stream, causing abnormal weather events in both the Arctic and mid-latitude regions, might be a consequence of growing atmospheric warmth in the Arctic.

Continued warming of the Arctic atmosphere in 2018 is an indicator of both regional and global climate change, and an agent of change throughout the Arctic environmental system. On land, atmospheric warming continued to drive broad, long-term trends in declining terrestrial snow cover, melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet and lake ice, increasing summertime Arctic river discharge, and the expansion and greening of Arctic tundra vegetation. Despite an increase in vegetation available for grazing, populations of caribou and wild reindeer herds across the Arctic tundra have declined by nearly 50% over the last two decades.

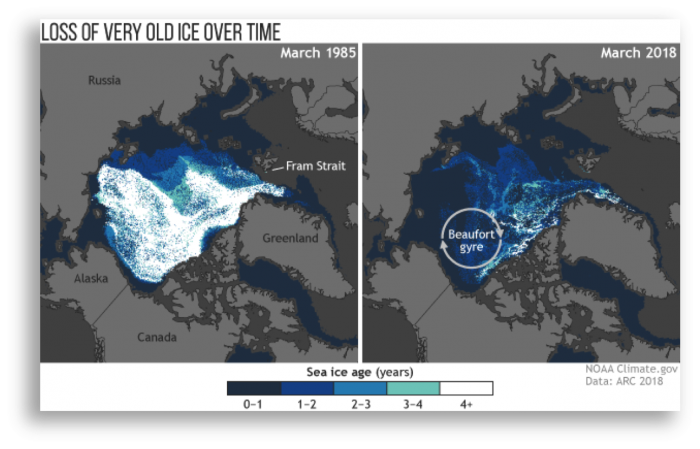

The influence of atmospheric warming is also seen in the marine system. In 2018, August mean sea surface temperatures showed statistically significant warming trends for 1982—2018 in most regions of the Arctic Ocean that were ice-free in August. The spatial patterns of late summer sea surface temperature are linked to the pace and extent of the changes to summer sea ice cover, along with regional air temperatures and advection of warm waters from the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. In 2018, Arctic sea ice remained younger, thinner, and covered less area than in the past (see Figure 2). In 1985, 16% of the ice pack was very old, thick multiyear ice. In 2018, old ice constituted less than 1% of the ice pack, meaning that very old Arctic ice has declined by 95% in the last 33 years. The disappearance of the older and thicker classes of ice are leaving an ice pack that is more vulnerable to melting in the summer. Pan-Arctic observations also suggest a long-term decline in coastal landfast sea ice since the 1970s, affecting an important habitat, and platform for hunting, traveling, and coastal protection for local communities.

One of the more remarkable features of Arctic sea ice in 2018 was the dearth of ice in the Bering Sea, which was at a record low extent for virtually the entire 2017—2018 ice season. Unprecedented declines of sea ice in the Bering Sea in winter 2018 had a profound effect on spring and summer Arctic Ocean primary productivity. The Bering Sea experienced earlier plankton blooms in March, with biomass in large areas of the region at 275% above average March values. Warming Arctic Ocean conditions are also coinciding with an expansion of harmful algae species responsible for toxic algal blooms in the Arctic Ocean. Considerable concentrations of algal toxins have been found in the tissues of Arctic clams, seals, walrus, and whales and other marine organisms. Microplastic contamination is also on the rise in the Arctic (particularly in the Barents Sea in the Atlantic sector), posing a threat to seabirds and marine life that ingest this debris.

The results reported in ARC 2018 show that the effects of persistent Arctic warming continue to mount. Long-term monitoring programs are critical to our understanding of baseline conditions and the magnitude and frequency of the changes that are occurring in the Arctic. Such understanding is central to the livelihood of communities that call the Arctic home, as well as the rest of planet Earth, which is already experiencing the changes and implications of a warming and thawing Arctic.

Further information is available on the NOAA Arctic Program website. Or, by downloading the full Arctic Report Card 2018.

About the Authors

Emily Osborne is a Program Manager for the NOAA Oceanic and Atmospheric Research Arctic Research Program. Emily, an early career scientist, also worked with NOAA's Arctic Research Program as a Sea Grant Knauss Fellow in 2017 after completing her graduate studies. She has served as an editor for the Arctic Report Card for two years and is also an editor for the Arctic Chapter of the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society (BAMS) annual State of the Climate report. Emily is actively involved with the Interagency Arctic Research Policy Committee as co-lead of the Environmental Intelligence Collaboration Team. She has also recently become involved with the International Arctic Science Committee (IASC) and serves as the Program Coordinator for the IASC Fellowship Program. She attended the University of South Carolina where she earned her PhD in Marine Science in 2016 studying marine microfossils and geochemistry and their applications to paleoclimate and paleo-ocean acidification research. She also holds an undergraduate degree in Geology from the College of Charleston.

Emily Osborne is a Program Manager for the NOAA Oceanic and Atmospheric Research Arctic Research Program. Emily, an early career scientist, also worked with NOAA's Arctic Research Program as a Sea Grant Knauss Fellow in 2017 after completing her graduate studies. She has served as an editor for the Arctic Report Card for two years and is also an editor for the Arctic Chapter of the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society (BAMS) annual State of the Climate report. Emily is actively involved with the Interagency Arctic Research Policy Committee as co-lead of the Environmental Intelligence Collaboration Team. She has also recently become involved with the International Arctic Science Committee (IASC) and serves as the Program Coordinator for the IASC Fellowship Program. She attended the University of South Carolina where she earned her PhD in Marine Science in 2016 studying marine microfossils and geochemistry and their applications to paleoclimate and paleo-ocean acidification research. She also holds an undergraduate degree in Geology from the College of Charleston.

Jackie Richter-Menge began her Arctic research career in 1981, when she joined the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL) in Hanover, New Hampshire. Jackie retired from CRREL in 2017 but continues to do some work via an affiliation with University Alaska Fairbanks. Her research activities focus on developing a more comprehensive understanding of the Arctic sea ice cover, providing observations that can be used to advance forecasts in support of near real time operational needs, and future projections associated with global climate variability. In 2016, Jackie was appointed to the U.S. Arctic Research Commission by President Obama.

Jackie Richter-Menge began her Arctic research career in 1981, when she joined the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL) in Hanover, New Hampshire. Jackie retired from CRREL in 2017 but continues to do some work via an affiliation with University Alaska Fairbanks. Her research activities focus on developing a more comprehensive understanding of the Arctic sea ice cover, providing observations that can be used to advance forecasts in support of near real time operational needs, and future projections associated with global climate variability. In 2016, Jackie was appointed to the U.S. Arctic Research Commission by President Obama.

Martin Jeffries has been with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL) since September 2018; he has particular responsibility for strengthening the Arctic science and engineering portfolio. As a researcher at the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF) between 1985 and 2014, he investigated sea ice in Antarctica and the Arctic Ocean, ice shelves and ice islands (tabular icebergs) in the Canadian High Arctic, and lake ice in Alaska. From 2006 to 2014, he was detailed first to the National Science Foundation, where he was the first Program Director for the Arctic Observing Network, and then to the Office of Naval Research (ONR), where he was an Arctic Science Advisor and Program Officer for Arctic and Global Prediction, and finally to the U.S. Arctic Research Commission as a Science Advisor. Immediately upon retiring from UAF in 2014, he became a career civil servant with ONR, from where he was detailed to Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) in the Executive Office of the U.S. President between February 2016 and March 2018.

Martin Jeffries has been with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL) since September 2018; he has particular responsibility for strengthening the Arctic science and engineering portfolio. As a researcher at the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF) between 1985 and 2014, he investigated sea ice in Antarctica and the Arctic Ocean, ice shelves and ice islands (tabular icebergs) in the Canadian High Arctic, and lake ice in Alaska. From 2006 to 2014, he was detailed first to the National Science Foundation, where he was the first Program Director for the Arctic Observing Network, and then to the Office of Naval Research (ONR), where he was an Arctic Science Advisor and Program Officer for Arctic and Global Prediction, and finally to the U.S. Arctic Research Commission as a Science Advisor. Immediately upon retiring from UAF in 2014, he became a career civil servant with ONR, from where he was detailed to Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) in the Executive Office of the U.S. President between February 2016 and March 2018.