By: John Farrell, Executive Director, U.S. Arctic Research Commission

Editor's Note: This article, originally published in the October 2017 issue of Witness Community Highlights, has been updated with new information and the newly-released map of "Identified Geographic Areas" related to the Agreement on Enhancing International Arctic Scientific Cooperation.

The eight member states of the Arctic Council vowed to improve cooperation on Arctic science via a legally binding agreement, entitled "Agreement on Enhancing International Arctic Scientific Cooperation" signed on 11 May 2017 at the Arctic Council Ministerial meeting in Fairbanks, Alaska. This was the third binding agreement initiated in the 20-year history of the Arctic Council. The first two focused on search-and-rescue and on oil-spill response.

In short, the goal of this science agreement is to facilitate access, whether to territory and research areas, platforms, infrastructure, facilities, materials, samples, data, or equipment. In the words of Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, the document promises to ease "the movement of scientists, scientific equipment and, importantly, data sharing" across the North. Barriers to research, such as denied visas, the inability to carry equipment and samples across national borders, or denial of access to data, preclude scientific investigation, slow progress, increase cost, and retard the growth of knowledge.

In addition to access, the agreement, which was designed to be inclusive, contains articles that discuss education, career development and training, traditional and local knowledge, and cooperation with parties other than the eight Arctic nations.

The U.S. and Russia successfully co-led the effort to reach this agreement, which required several years of discussion and negotiation under the auspices of an Arctic Council Task Force. This cooperative effort was an uncommon bright light in a currently dark chapter of U.S.-Russia relations. This agreement, and the Arctic Science Ministerial meeting held at the White House on 28 September 2016, are examples of how science and research across borders can advance diplomatic efforts through soft power, rather than coercion. Paul Berkman and co-authors published a paper on this agreement titled, "The Arctic Science Agreement propels science diplomacy" in the 3 November 2017 issue of Science.

Although signed, the agreement will not "enter into force" until 30 days after all eight parties have indicated that they have completed all necessary internal procedures required to enforce the agreement. At the time of this publication, the U.S., Sweden, Norway, and Finland have informed Denmark, the "depositary" for the agreement, that they have completed the steps necessary to implement the agreement. The final four signatories (Russia, Canada, Iceland, and Denmark) have yet to inform the depositary.

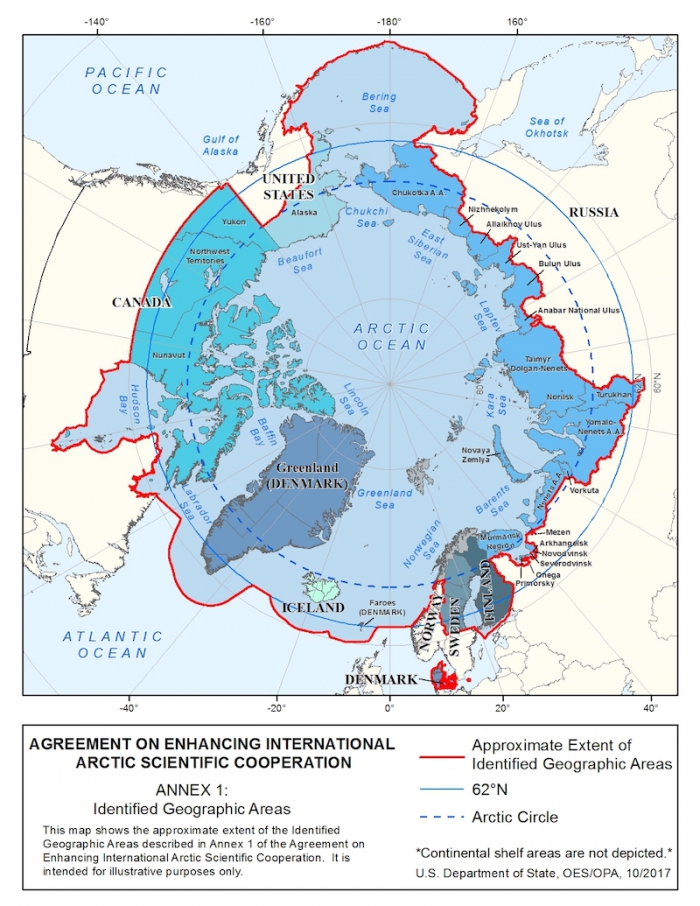

Each party identified geographic areas over which the agreement pertains. These are contained in an annex to the agreement. The U.S. Department of State has created a map that graphically displays these areas (see Figure 1).

For the U.S., the area is the Arctic region as defined in the Arctic Research and Policy Act of 1984 as amended, and is "All United States territory north of the Arctic Circle and north and west of the boundary formed by the Porcupine, Yukon, and Kuskokwim Rivers; the Aleutian chain; and adjacent marine areas in the Arctic Ocean and the Beaufort, Bering, and Chukchi Seas." Maps of the U.S. Arctic may be found on the U.S. Arctic Research Commission (USARC) website.

In practice, will this agreement enhance Arctic scientific cooperation? While the intent is positive, some question whether it will do so, as the document has several escape clauses.

For example, the agreement includes phrases such as, "…shall use their best efforts…," and "Implementation of this Agreement shall be subject to the availability of relevant resources." And Article 10 reads, "Activities and obligations under this Agreement shall be conducted subject to applicable international law and the applicable laws, regulations, procedures, and policies of the Parties concerned. For those Parties that have subnational governments, the applicable laws, regulations, procedures, and policies include those of their subnational governments."

So, it remains possible to deny access despite best efforts that fail, or to insufficient resources to facilitate access, or to existing procedures or policies that run counter to the goals of the agreement.

In essence, the validity of the agreement will only be determined when it is exercised. If denials of access and other challenges can be overcome through discussion and negotiation facilitated under this agreement, then it will have merit. The proof will be in the pudding.

The parties to the agreement are currently in the process of establishing specific procedures and processes necessary to implement the agreement, and a Terms of Reference may be established.

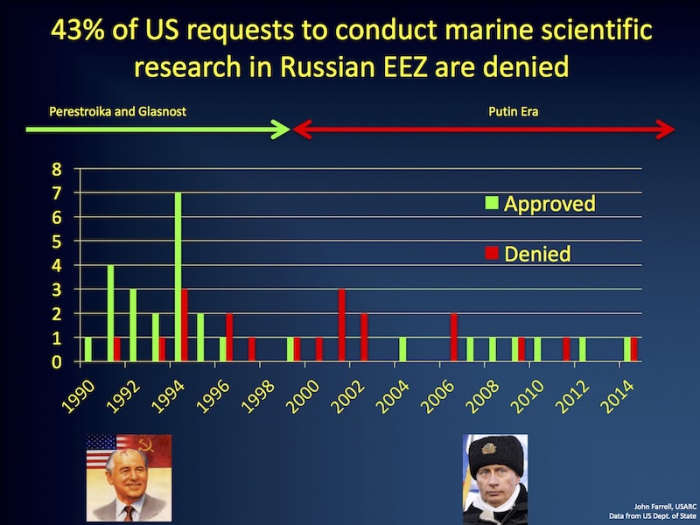

Generally speaking, Arctic researchers have benefitted from good access to the pan-Arctic region, but this is not always the case. For example, entering the Russian Federation has sometimes proven difficult. Between 1990 and 2014, the U.S. Department of State submitted 48 requests to Russia for U.S. vessels to conduct marine scientific research in the Russian Exclusive Economic Zone. Of those requests, 20, representing 42%, were either denied or elicited no response, which the State Department considers to be denial of access (See Figure 2).

In the agreement, each party designated an entity to serve as the "competent national authority" as the responsible point of contact for the agreement. The United States selected the U.S. Arctic Research Commission. Projecting forward, we look forward to exercising the optimism and enthusiasm for cooperation displayed in the effort to reach this agreement and to facilitating research for the greater good.

Who do you call if there is a problem?

If you are a U.S.-based scientist facing a challenge covered by the agreement, please contact the U.S. Arctic Research Commission by phone (703-525-0111) or via email (info [at] arctic.gov).

The Agreement on Enhancing International Arctic Scientific Cooperation is available online here.

Or, download a PDF here.

More information about the USARC is available on the USARC website.

John Farrell is the Executive Director of the U.S. Arctic Research Commission, an independent federal agency of Presidential appointees that advises the White House and Congress on Arctic research matters and works with executive branch agencies to establish and execute a national Arctic research plan. The Commission also facilitates cooperation with local and state governments and recommends means for developing international scientific cooperation in the Arctic.

John Farrell is the Executive Director of the U.S. Arctic Research Commission, an independent federal agency of Presidential appointees that advises the White House and Congress on Arctic research matters and works with executive branch agencies to establish and execute a national Arctic research plan. The Commission also facilitates cooperation with local and state governments and recommends means for developing international scientific cooperation in the Arctic.