Outlook Report

Executive Summary

We thank those who contributed to this 2022 September Sea Ice Outlook (SIO) report. This activity is only possible through the dedicated participation of the many forecast contributors. The 2022 September Sea Ice Outlook received 22 submissions (28 in August, 30 in July, 37 in June). These outlook contributions are based on various methods, including dynamical (physics-based) models, statistical approaches including machine-learning (ML), and heuristic (qualitative). Along with projections of total Arctic sea-ice extent for September, the August SIO received seven projections of Antarctic total ice extent (nine in each June, July, and August SIOs) and seven projections of ice extent in the Alaskan sector, which combines the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort seas (eight in the August and June SIOs and ten in the July SIO). Sea-ice probability (SIP) forecasts from seven models are included in the September 2022 SIO. For the second year, the SIO solicited September mean Arctic sea-ice extent anomaly forecasts and received ten in September (12 in the August SIO, ten in the June SIO and eight in the July SIO).

The pan-Arctic September Outlook median forecast value for September 2022 sea-ice extent is 4.90 million square kilometers, with lower and upper quartile values of 4.8 and 5.0 million square kilometers, respectively. The median of the September 2022 submissions is greater than that from August (4.83 million square kilometers), July (4.64 million square kilometers), and June (4.57 million square kilometers) of 2022.

Based on the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) Sea Ice Index (SII), the Arctic sea-ice extent index is 4.67 million square kilometers, as of 18 September 2022. As of mid-September, ice extent was lower than the 1980–2010 average in nearly all sectors of the Arctic Ocean. The Northern Sea Route and the Northwest Passage were largely free of ice. As the atmosphere has cooled, the openings near the North Pole north of the Kara Sea have largely closed. Air temperatures (at the 925 mb level) from mid-August to mid-September were above average over much of the Arctic. In the Beaufort Sea, temperatures were about 2.5 C above average. In the Kara and Laptev Seas, temperatures were near normal. Over the same period, a typical Beaufort Sea high was present, albeit relatively small; low pressure was found in the coastal Eurasian seas.

For Antarctica, similar to the previous forecasts this season, 2022 is anticipated to be a low year. The persistence forecast, and five out of seven forecasts, predict a negative anomaly relative to the climatological value.

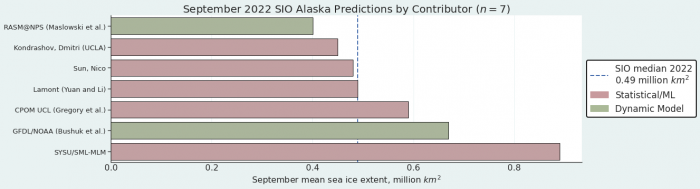

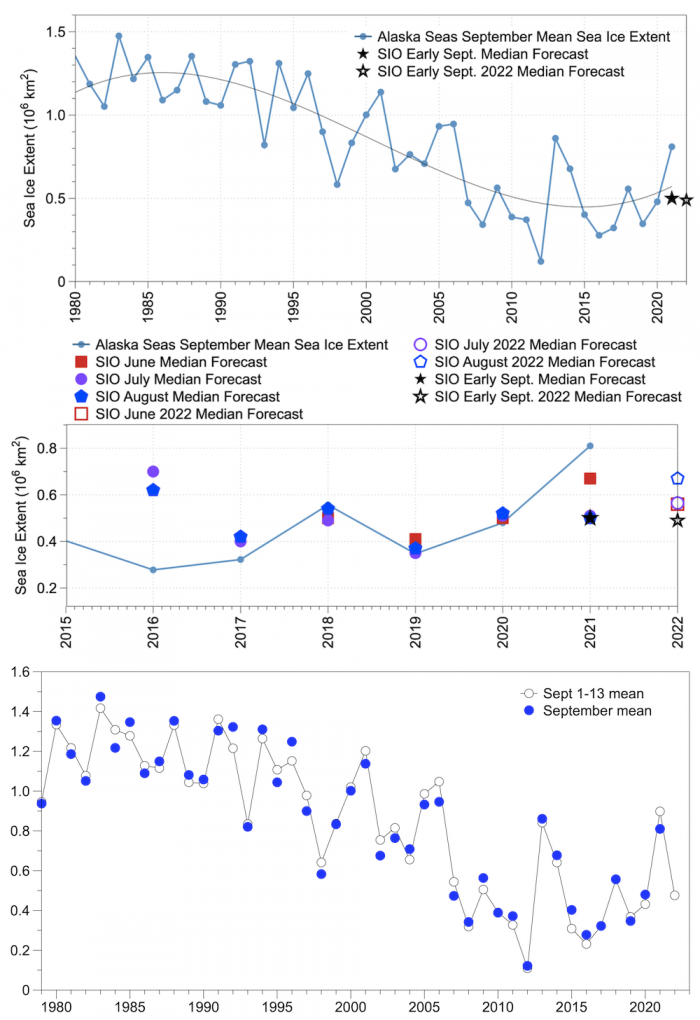

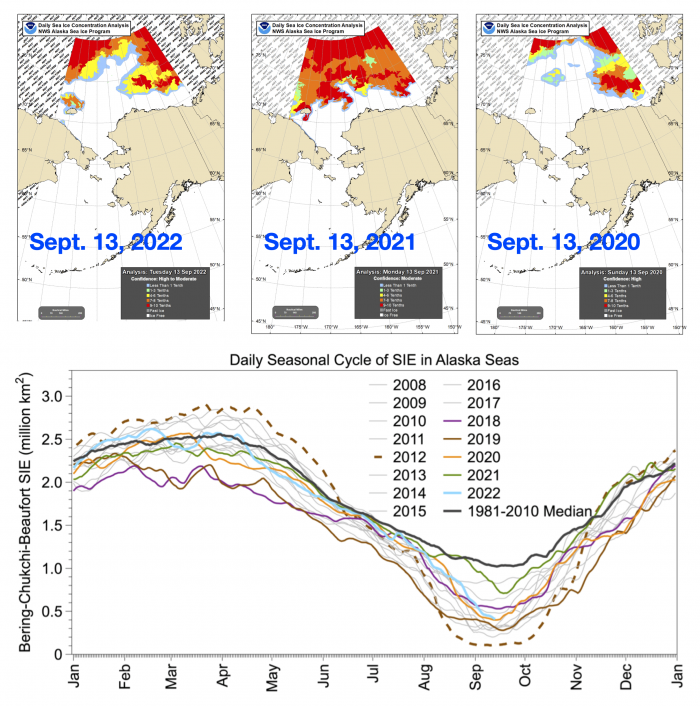

For the Alaskan regional sea-ice extent, a median value of 0.49 million square kilometers was predicted from the seven contributions to the September SIO based on statistical/ML and dynamical methods. The September 2022 SIO forecasts continue to predict Alaska sea-ice extent (Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort seas) greater than the 2007–2021 average of 0.40 million square kilometers. The 13 September value for 2022 is below 2021 (0.79 million square kilometers) on the same day but above the 2019 and 2020 values which were 0.31 and 0.39 million square kilometers, respectively.

This September Outlook Report was developed by lead author Uma Bhatt, University of Alaska Fairbanks (Executive Summary, Overview, discussion of pan-Arctic anomaly sea-ice forecasts and ice conditions in the Bering and Chukchi seas); with contributions from Mark Serreze and Walt Meier, National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC; discussions of current Arctic conditions); Edward Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, University of Washington (discussion of predictions from spatial fields); Michael Steele, University of Washington, Applied Physics Laboratory (discussion of Ocean Heat Conditions); François Massonnet, Université catholique de Louvain (Discussion of Antarctic contributions); Matthew Fisher and the NSIDC Development Team, (statistics and graphs); Betsy Turner-Bogren, Helen Wiggins, Kuba Grzeda, Lisa Sheffield Guy, and Stacey Stoudt, ARCUS (report coordination and editing); and the rest of the SIPN2 Project Team.

Note: The Sea Ice Outlook provides an open process for those who are interested in Arctic sea-ice to share predictions and ideas; the Outlook is not an operational forecast.

See: September Call for Contributions

2022 SIO Forecasts (Pan-Arctic, Alaska Region, Spatial Forecasts, and Antarctic)

Pan-Arctic Forecasts

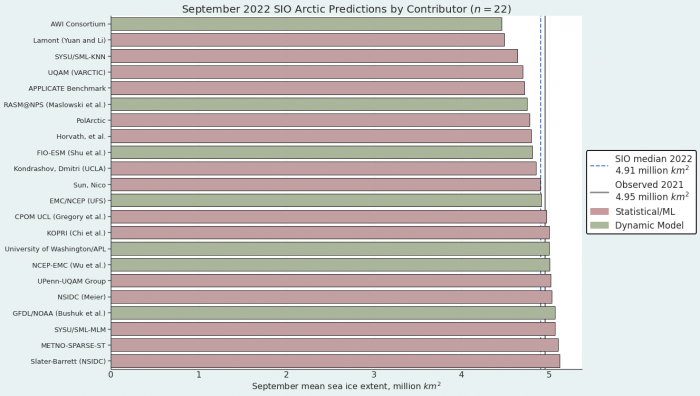

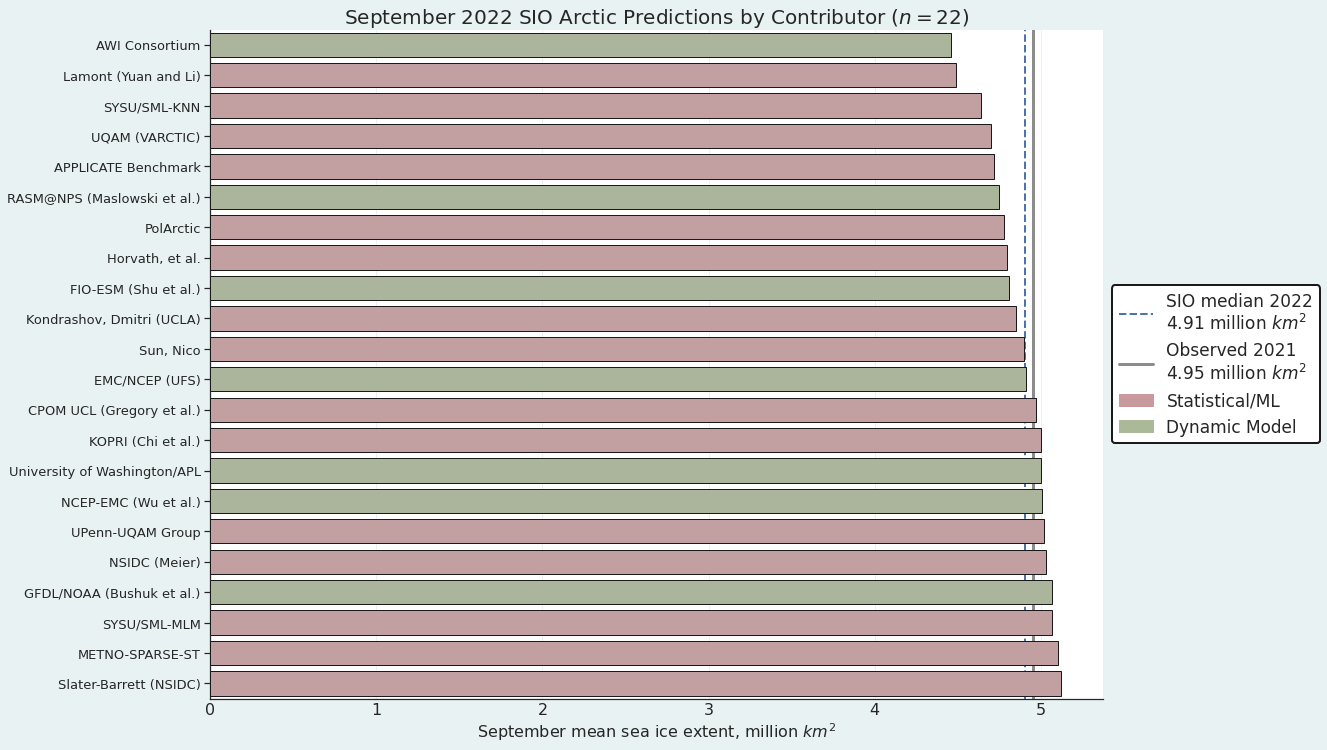

The September Outlook is based on a total of 22 forecasts (Figure 1) and the median September value for the September 2022 sea-ice extent is 4.90 million square kilometers with quartile values of 4.8 and 5.0 million square kilometers. This interquartile range (IQR) of 0.2 million square kilometers is smaller than September 2021, which had quartile values of 4.1 and 4.7 million square kilometers and an IQR of 0.6 million square kilometers. Of the September 2022 contributions, six are based on dynamical models and 15 are based on statistical/machine learning-based methods. The median of the September 2022 submissions is greater than that from August (4.83 million square kilometers), July (4.64 million square kilometers), and June (4.57 million square kilometers) of 2022. The 2022 September Outlook median is over 0.5 million square kilometers higher than the 2021 September Outlook median (4.39 million square kilometers).

For the 2022 SIO September report, six groups submitted supplemental materials (see: Contributor Full Reports and Supplemental Materials below). The supplemental material contents vary among the contributions, but they may include information on methodology on: (1) how the forecasts are produced; (2) number of ensemble members used in the forecasts; (3) whether and how bias-corrections are applied; (4) ensemble spread, range of forecasts, uncertainties and other statistics; and (5) whether or not post-processing was performed.

The median value in the September 2022 Outlook was close for the dynamical (4.91 million square kilometers) and statistical methods (4.9 square kilometers). The corresponding ranges are 4.46 to 5.07 million square kilometers for the dynamical model forecasts and 4.49 to 5.12 million square kilometers for the statistical forecasts (Figure 2). As shown in Figure 2, the quartile range of the dynamical and statistical model forecasts issued in September are equal or smaller than the corresponding ranges of the August, July, and June forecasts, suggesting a decrease in uncertainty. In contrast, the 2021 SIO quartile range of statistical and ML methods increased from August to September, while dynamical remained the same.

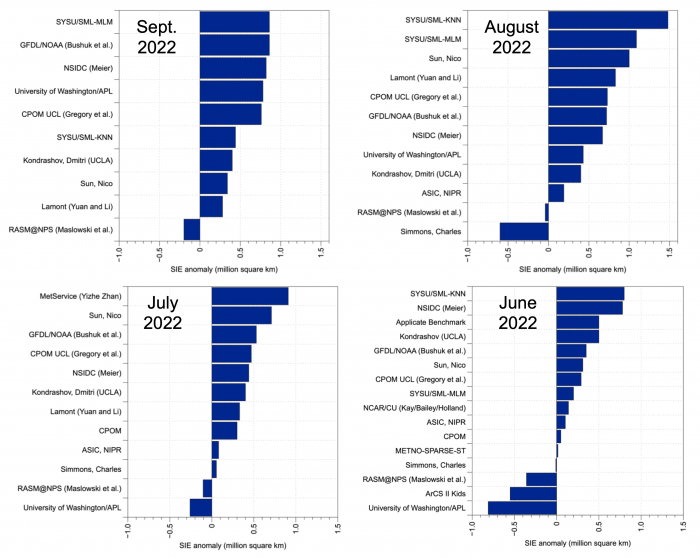

Pan-Arctic Sea-ice Extent Anomalies

This is the second year that the SIO has solicited forecasts of September mean sea-ice extent anomalies. The anomaly is the departure of the contributors' September extent outlook relative to their adopted baseline trend (e.g., the trend in historical observations, model hindcasts, etc.), motivated by the prospect of reducing SIO extent forecast uncertainty that may originate from models having different trends, mean states, and post-processing methodologies. The 10 anomaly forecasts for September range from -0.20 to +0.86 million square kilometers, with nine forecasts above and one below the contributors' baseline (Figure 3, top). The September SIO anomaly forecast range spans 1.01 million square kilometers compared to the August, July, and June SIO ranges of 2.08, 1.2, and 1.6 million square kilometers, respectively (Figure 3). The pan-Arctic September SIO anomaly forecast has a median of 0.6 million square kilometers compared to an August SIO median of 0.695, a July SIO median of 0.37 and a June median of 0.17. The September dynamical forecasts (n = 3) have a higher median (0.78 million square kilometers) than the statistical forecasts (0.44 million square kilometers; n = 7). September has a standard deviation of 0.34 million square kilometers closer to July (0.33 million square kilometers) and June (0.44 million square kilometers) and smaller compared to that of August (0.53 million square kilometers). As the 2022 season has progressed, the number of negative SIO pan-Arctic September mean anomaly forecasts decreased.

September 2022 SIO Comparison with September 2021

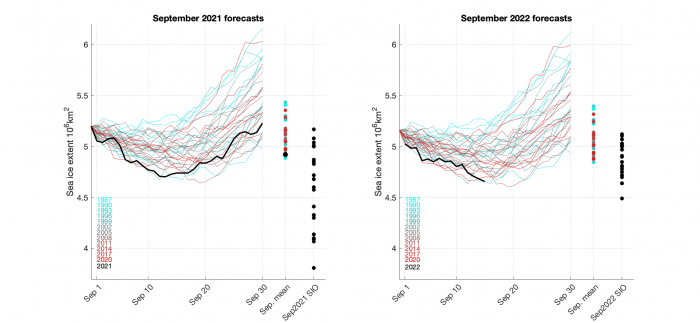

By early September, given the seasonal timescale of sea-ice extent anomalies, an accurate forecast can be made using the August 31st sea-ice extent and historical tendencies of sea-ice extent (a damped anomaly September sea-ice extent forecast made on 1 September is very skillful with an RMSE of just 0.1 million square kilometers). In 2021—the first year we invited forecasts in September—many forecasts were outside the range expected from historical tendencies of sea-ice extent, as we noted in the 2021 Post-Season Report.

Figure 4 shows the same analysis for this year. Using the observed 31 August 2022 sea-ice extent value (SIE = 5.15 million square kilometers) and past (1987–2021) daily September tendencies, we expect September 2022 SIE to be between 4.8 and 5.4 million square kilometers, and values outside this range essentially require unprecedented rates of SIE change through the month of September. This year, forecasts are better grouped with respect to the simple forecast than in 2021, yet we note there are still quite a few models that forecast lower values than 4.8 million square kilometers.

Alaska Regional Forecasts

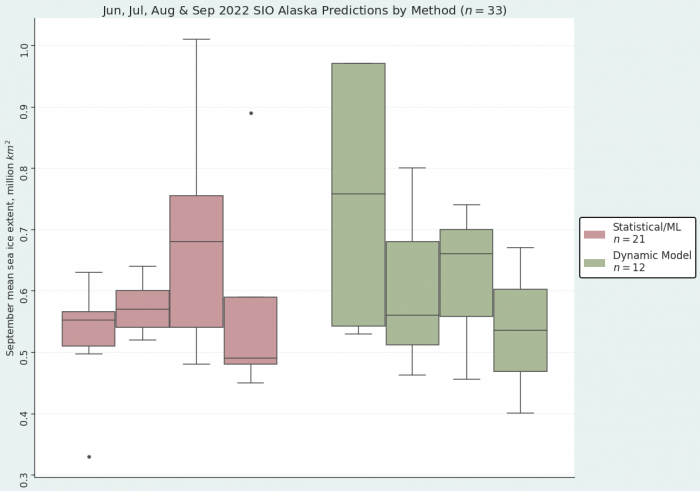

The multi-modal median for the September 2022 SIO forecast for the Alaska seas is 0.49 million square kilometers and consists of seven contributions with values ranging from 0.40 to 0.89 million square kilometers (Figure 5). The dynamical model forecasts range from 0.40 to 0.67 million square kilometers with a median of 0.54 million square kilometers. The statistical model forecasts range from 0.45 to 0.89 million square kilometers with a median of 0.49 million square kilometers. For the September SIO, the statistical forecasts display a larger range compared to the dynamical models (Figure 6), as was the case for the August SIO. To place these in historical perspective, the September median sea-ice extent for the averaged Alaska seas (Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort) over 2007–2021 is 0.40 million square kilometers (Figure 7, top), making the median September forecast for 2022 closer to recent observed values between 2015 and 2020 than August SIO median forecast (Figure 7, middle). June–August SIO median forecasts were close to observations in 2017 through 2020, while the 2021 forecast was much lower than observed. Daily averaged sea-ice extent from September 1–13 is compared to the September mean in Figure 7 (bottom) and the close correspondence over the record suggests that the 2022 observed values will be close to the September SIO median forecast of 0.49 million square kilometers.

Pan-Arctic Forecasts with Spatial Methods

Sea Ice Probability (SIP)

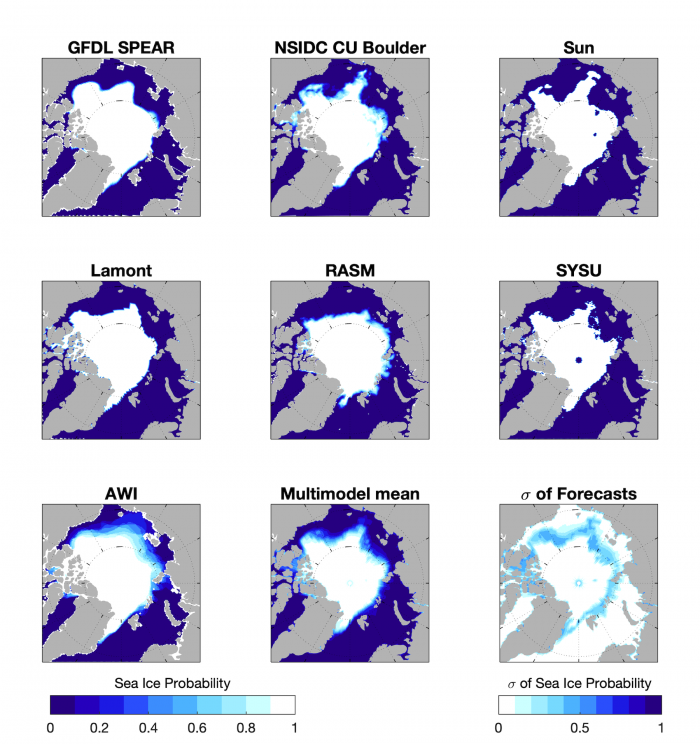

We have received seven forecasts of sea-ice probability, shown in Figure 8. While some models show sea-ice cover persisting in the East Siberian Sea (NSIDC, Sun, SYSU and to a lesser extent GFDL SPEAR) in an elongated ice tongue, other forecasts show a more zonal sea-ice edge in this region (e.g., RASM). Model forecasts (with the exception of RASM) are very consistent in the European Arctic (north Kara, Barents, and East Greenland seas) and forecast a sea-ice edge just to the north of Svalbard and Franz Josef.

Antarctic Forecasts

For this round of September forecasts, we received seven contributions (Figure 9). The forecast spread is still large (comparable to interannual variability) despite the proximity between the forecast submission (12 September) and the targeted metric (September mean). The persistence forecast and five out of seven forecasts predict a negative anomaly relative to the climatological value.

Current Conditions

Pan-Arctic Conditions

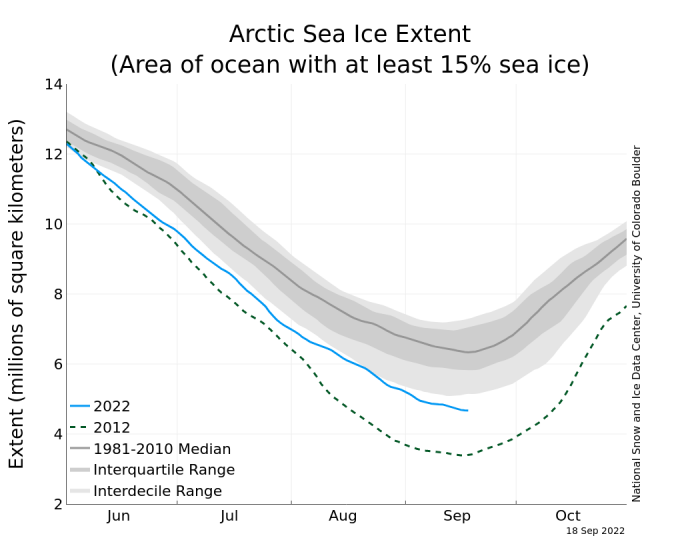

Based on data from the NSIDC Sea Ice Index, average Arctic sea-ice extent for August 2022 was 5.99 million square kilometers, ranking 13th lowest in the 44-year satellite record. This was 1.21 million square kilometers below the 1981 to 2010 August average. The decline in extent during August was near the climatological average for the first half of the month, but exceeded the average rate over the second half of the month. For a brief period in mid-August, the extent approached the lower interdecile range, but then diverged as the 2022 extent drop continued at a pace relative to normal. By early September, in accord with the decline in solar radiation and falling temperatures, the decline rate usually slows. However, in 2022, the extent continued steadily downward through the first half of September. By 18 September, with the minimum daily extent likely imminent, the extent stood at 4.67 million square kilometers (Figure 10).

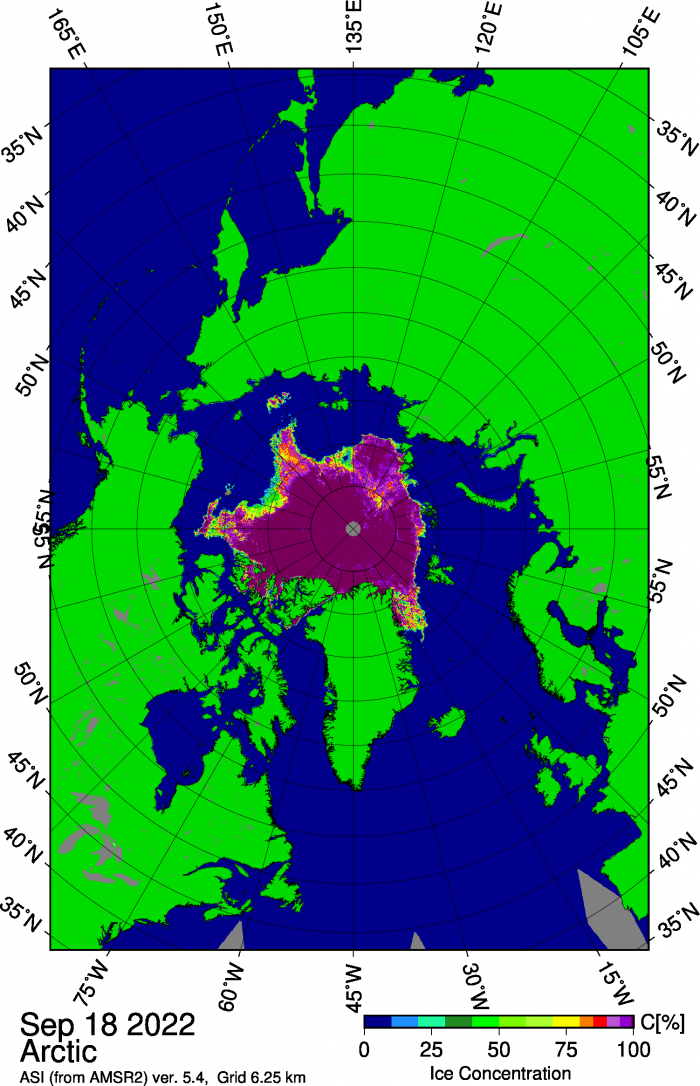

Sea-ice extent was lower than the 1981–2010 average in nearly all sectors of the Arctic Ocean. The Northern Sea Route and Northwest Passage routes were largely ice-free by the end of August. The area of low concentration ice and small areas of open water that persisted north of the Kara Sea—nearly to the pole—have largely frozen up (Figure 11).

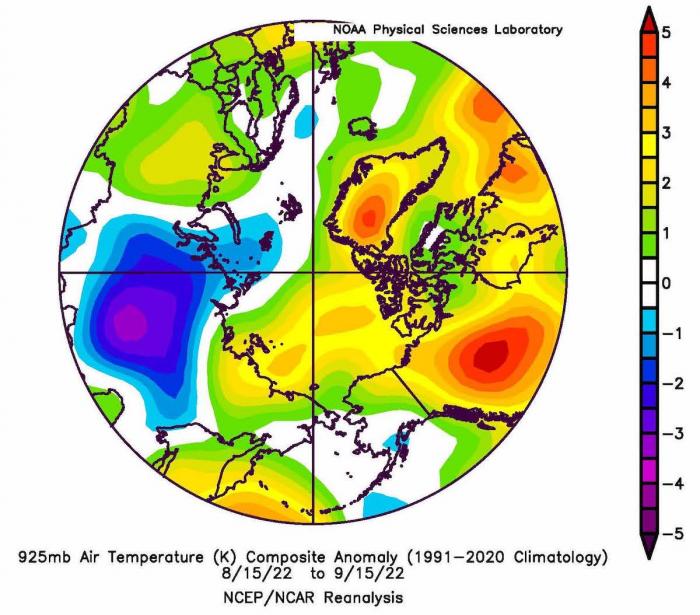

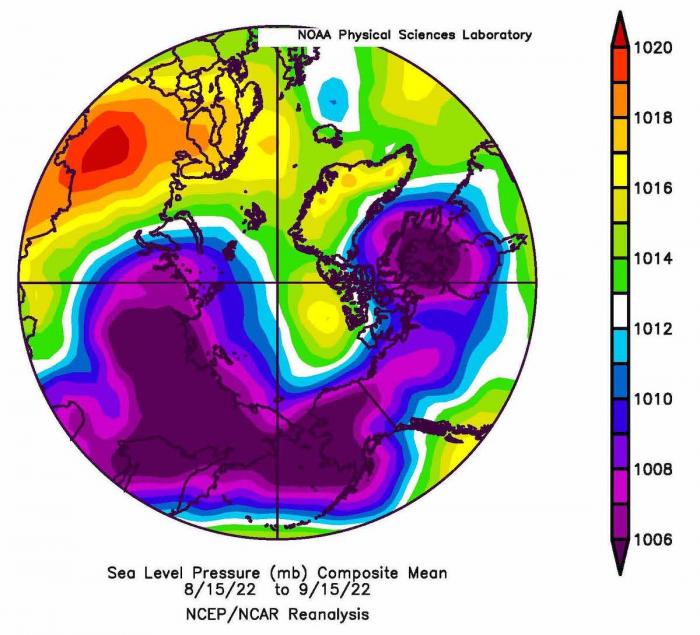

Air temperatures (at the 925 mb level) from mid-August to mid-September were above average over much of the Arctic Ocean. In the Beaufort Sea, temperatures were about 2.5 C above average (Figure 12). In the Kara and Laptev seas, temperatures were near average. Over the same period, a Beaufort Sea high was present, covering a fairly small area (Figure 13); low pressure was found in the coastal Eurasian seas.

Alaska Regional Conditions

Mid-September 2022 sea-ice extent displays lower ice concentration and more open water in the central Chukchi and Beaufort seas compared to the 2021 mid-September conditions (Figure 14, top). In 2020, sea-ice concentration retreated slightly farther north than in 2022. The combined Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort sea-ice extent was slightly lower than the 1981–2010 average from mid-April to mid-August 2022 (Figure 14, bottom). Since mid-August, the retreat of sea ice has been strong and the total area is close to that in 2020. The 13 September extent is 0.41 million square kilometers in 2022, which is below the 1981–2010 median value of 1.02 million square kilometers. The 13 September value for 2022 is below 2021 on the same day but above the 2019 and 2020 values which were 0.31 and 0.39 million square kilometers, respectively (Figure 14, right). Sea-ice extent was lower in the Chukchi (2022: 0.22 v.s. 2021: 0.39 million square kilometers) and Beaufort Seas (0.71 vs. 0.77 million square kilometers) on 13 September 2022 compared to the same day in 2021 based on the NSIDC data. It is still unlikely that the 2019 September mean extent in the Alaska seas will be surpassed in 2022 as the melt season winds down.

Ocean Heat Conditions

In mid-September 2022 (Figure 15), the Beaufort Sea looks like the past few years (a "new normal?") with old, relatively thick ice that streamed into the region from north of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago over the previous winter (especially present in the eastern Beaufort). This ice co-exists in a complex ice-edge geometry with cold water that is the signature of recently melted ice (especially present in the western Beaufort). There is a tongue of ice in the East Siberian Sea, which is an area that usually melts out relatively late (if at all); a comparison with a similar situation in 2018 is provided in the figure. Interestingly, the band of cold, near-freezing waters indicating late summer ice-melt that has been quite wide (2-3 degrees of latitude) in recent years along the Eurasian ice margin (not shown) is much thinner this year.

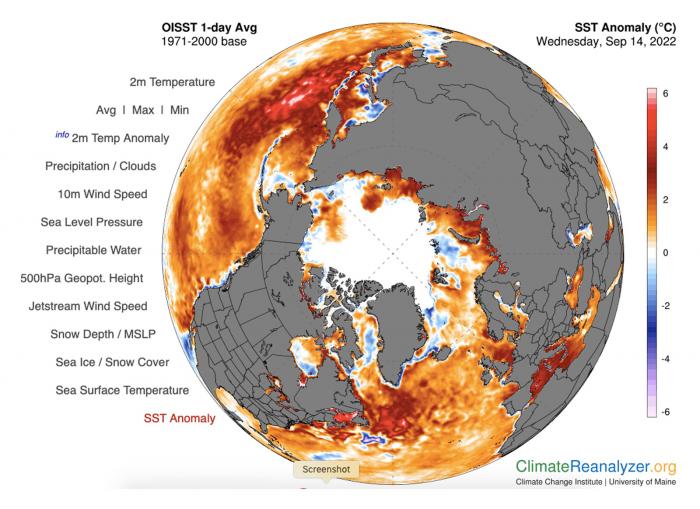

Pan-Arctic SST anomalies are presented in Figure 16. Cool anomalies in both the Pacific and Atlantic subarctic seas that were present a month ago (see August SIO report) are not so obvious in mid-September. High amplitude anomalies within the Arctic Ocean are largely absent, except on the inner Russian Arctic shelves.

Contributor Key Statements, Summary of Uncertainties

![]() Summary Table of Key Statements from Individual Outlooks—per 21 September 2022 (PDF - 114 KB)

Summary Table of Key Statements from Individual Outlooks—per 21 September 2022 (PDF - 114 KB)

Contributor Full Report PDFs and Supplemental Material

This report was developed by the SIPN2 Leadership Team.

Report Lead:

Uma Bhatt, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Geophysical Institute

Additional Contributors:

Matthew Fisher and the NSIDC Development Team, Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder, NSIDC

Editors:

Betsy Turner-Bogren, ARCUS

Helen Wiggins, ARCUS

Kuba Grzeda, ARCUS

Stacey Stoudt, ARCUS

Lisa Sheffield Guy, ARCUS

Suggested Citation:

Bhatt, U.S., P. Bieniek, E. Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, H. Eicken, M. Fisher, L. C. Hamilton, J. Little, F. Massonnet, W. Meier, J.E. Overland, M. Serreze, M. Steele, J. Stroeve, J. Walsh, M. Wang, and H. V. Wiggins. Editors: Turner-Bogren, B., L., Sheffield Guy, J.K. Grzeda, S. Stoudt, and H. V. Wiggins. September 2022. "Sea Ice Outlook: 2022 September Report." (Published online at: https://www.arcus.org/sipn/sea-ice-outlook/2022/september)

This Sea Ice Outlook Report is a product of the Sea Ice Prediction Network–Phase 2 (SIPN2), which is supported in part by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. OPP-1748308. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.