Outlook Report

Executive Summary

We thank those who contributed to this 2022 August Sea Ice Outlook (SIO) report. This activity is only possible through the dedicated participation of the many forecast contributors. The 2022 August Sea Ice Outlook received 28 submissions (37 in June, 30 in July). These outlook contributions are based on various methods, including dynamical (physics-based) models, statistical approaches including machine-learning, and heuristic (qualitative). Along with projections of total Arctic sea-ice extent for September, the August SIO received nine projections of Antarctic total ice extent (same number as in June and July SIOs) and eight projections of ice extent in the Alaskan sector, which combines the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort seas (eight in the June SIO and ten in the July SIO). Sea-ice probability (SIP) forecasts from nine models and six first ice-free dates (IFD) are included in the August 2022 SIO. For the second year, the SIO solicited September mean Arctic sea-ice extent anomaly forecasts and received 12 in August (ten in the June SIO and eight in the July SIO).

The Pan-Arctic August Outlook median forecast value for September 2022 sea-ice extent is 4.83 million square kilometers, with upper and lower quartile values of 4.6 and 5.0 million square kilometers, respectively. The median of the August submissions is higher than that from July (4.64 million square kilometers) and June (4.57 million square kilometers). Based on the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) Sea Ice Index (SII), the Arctic sea-ice extent index is 6.16 million square kilometers, as of 15 August 2022. As of mid-August, ice extent was lower than normal in most sectors of the Arctic Ocean, with the exceptions being the Beaufort Sea where the ice edge was near normal, and most notably the East Siberian Sea, where ice still extended to the coast. The atmospheric circulation in July to mid-August tended towards cloudier skies and spreads out the ice, both of which can slow the decline in ice extent and result in higher September mean sea-ice extent if such conditions prevail. It will be interesting to see if the mean September sea-ice extent in 2022 is above 5.0 million square kilometers. While none of the July-August median forecasts were 5.0 million square kilometers, nine of the 28 August SIO contributions forecast 5.0 million square kilometers or more for September mean sea-ice extent.

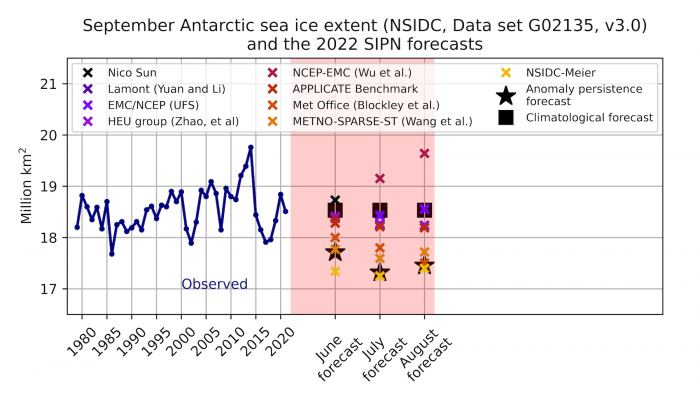

For Antarctica, similar to the previous forecasts this season, 2022 is anticipated to be a low year and possibly even a record one. Except for one outlier, all forecasts agree that the value for September will be below climatology.

For the Alaskan regional sea-ice extent, a median value of 0.67 million square kilometers was predicted from the eight contributions based on statistical/ML and dynamical methods. The August 2022 SIO forecasts continue to predict Alaska sea-ice extent (Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort seas) greater than the 2007–2021 average of 0.40 million square kilometers. As of 15 August 2022, sea-ice extent in the Alaskan seas is 0.91 million square kilometers, which is below 2020 and 2021 values for this day, but above the 2019 value of 0.44 million square kilometers.

This August Outlook Report was developed by lead author Uma Bhatt, University of Alaska Fairbanks (Executive Summary, Overview, discussion of pan-Arctic anomaly sea-ice forecasts and ice conditions in the Bering and Chukchi seas); with contributions from Mark Serreze and Walt Meier, National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC; discussions of current Arctic conditions); Edward Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, University of Washington (discussion of predictions from spatial fields); Michael Steele, University of Washington, Applied Physics Laboratory (discussion of Ocean Heat Conditions); François Massonnet, Université catholique de Louvain (Discussion of Antarctic contributions); Matthew Fisher and the NSIDC Development Team, (statistics and graphs); Betsy Turner-Bogren, Helen Wiggins, Kuba Grzeda, Lisa Sheffield Guy, and Stacey Stoudt, ARCUS (report coordination and editing); and the rest of the SIPN2 Project Team.

Note: The Sea Ice Outlook provides an open process for those who are interested in Arctic sea ice to share predictions and ideas; the Outlook is not an operational forecast.

See: August Call for Contributions

2022 SIO Forecasts (Pan-Arctic, Alaska Region, Spatial Forecasts, and Antarctic)

Pan-Arctic Forecasts

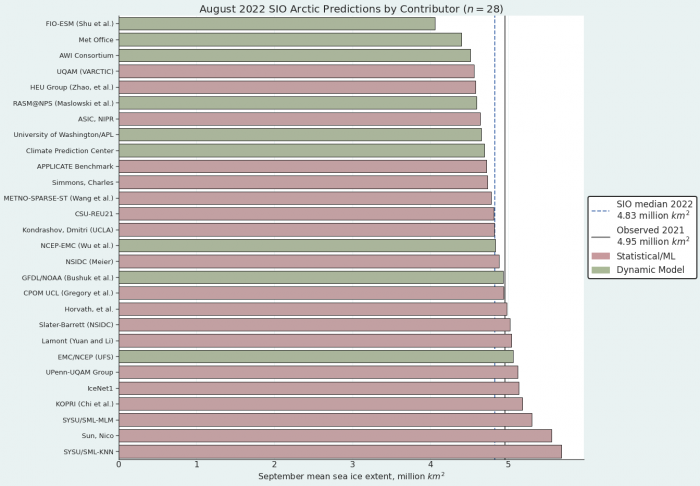

The August Outlook is based on a total of 28 forecasts (Figure 1) and the median August value for the September 2022 sea-ice extent is 4.83 million square kilometers with quartile values of 4.6 and 5.0 million square kilometers. Of the August 2022 contributions, nine are based on dynamical models and 19 are based on statistical/machine learning-based methods. The median of the August 2022 submissions is greater than that from July (4.64 million square kilometers) and June (4.57 million square kilometers) of 2022. The 2022 August Outlook median is higher than the August Outlook medians in 2021 (4.39 million square kilometers), 2020 (4.30 million square kilometers), 2019 (4.22 million square kilometers), and 2018 (4.57 million square kilometers). The June and July median SIO forecast for 2022 is above those of previous years except 2018 (Table 1).

For the 2022 SIO August report, eight groups submitted supplemental materials (see: Contributor Full Reports and Supplemental Materials below). The supplemental material contents vary among the contributions, but they may include information on methodology on: (1) how the forecasts are produced; (2) number of ensemble members used in the forecasts; (3) whether and how bias-corrections are applied; (4) ensemble spread, range of forecasts, uncertainties and other statistics; and (5) whether or not post-processing was performed.

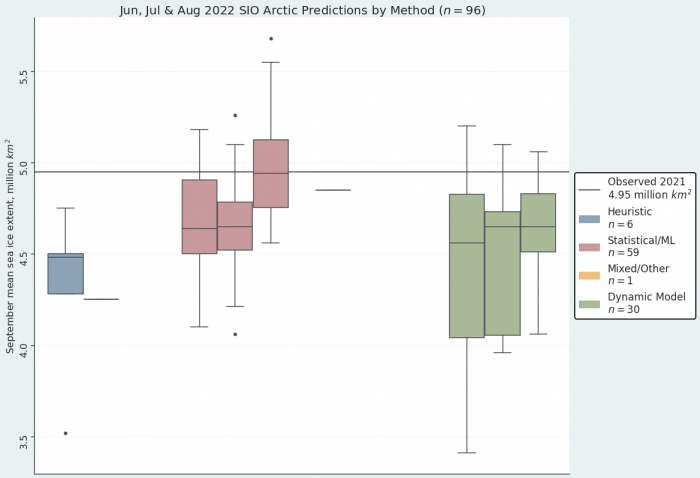

The median value in the August 2022 Outlook was lower for the dynamical (4.65 million square kilometers) compared to that of statistical methods (4.94 square kilometers), similar to August 2021. The corresponding ranges are 4.1 to 5.1 million square kilometers for the dynamical model forecasts and 4.6 to 5.7 million square kilometers for the statistical forecasts (Figure 2). As shown in Figure 2, the quartile range of the dynamical and statistical model forecasts issued in August are equal or smaller than the corresponding ranges of the July and June forecasts, suggesting a decrease in uncertainty. In contrast, the 2021 SIO quartile range of statistical and dynamical forecasts increased from June to August.

| Year | June | July | August |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 4.57 | 4.64 | 4.83 |

| 2021 | 4.37 | 4.36 | 4.39 |

| 2020 | 4.33 | 4.36 | 4.30 |

| 2019 | 4.40 | 4.28 | 4.22 |

| 2018 | 4.60 | 4.70 | 4.57 |

| 2017 | 4.43 | 4.50 | 4.54 |

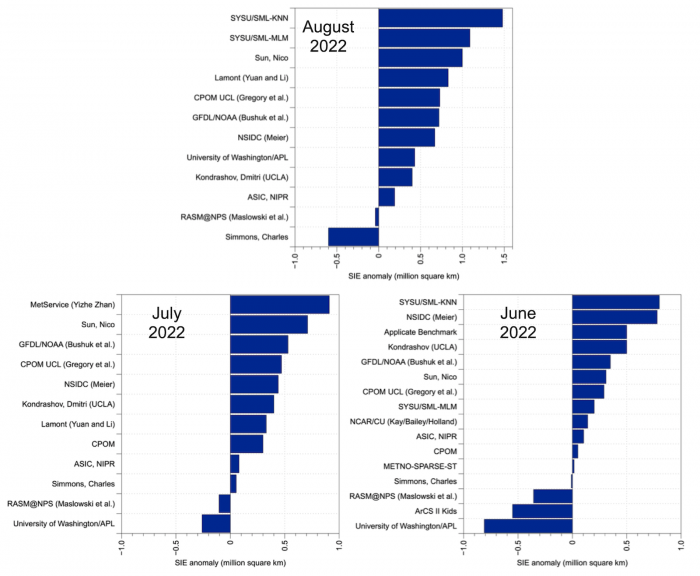

This is the second year that the SIO has solicited forecasts of September mean sea-ice extent anomalies. The anomaly is the departure of the contributors' September extent outlook relative to their adopted baseline trend (e.g., the trend in historical observations, model hindcasts, etc.), motivated by the prospect of reducing SIO extent forecast uncertainty that may originate from models having different trends, mean states, and post-processing methodologies. The 12 anomaly forecasts for August range from -0.6 to +1.48 million square kilometers, with 10 forecasts above and two below the contributors' baseline (Figure 3, top). The August SIO anomaly forecast range spans 2.08 million square kilometers compared to the July and June SIO ranges of 1.2 and 1.6 million square kilometers, respectively (Figure 3, bottom). The pan-Arctic August SIO anomaly forecast has a median of 0.695 million square kilometers compared to a July SIO median of 0.37 and a June median of 0.17. The August dynamical forecasts (n = 3) have a lower median (0.43 million square kilometers) than the statistical forecasts (0.73 million square kilometers; n = 9). August has a standard deviation of 0.53 million square kilometers, which was larger than the July (0.33 million square kilometers) and June (0.44 million square kilometers) standard deviations. As the 2022 season has progressed, the median SIO pan-Arctic September mean anomaly forecast has become more positive.

Alaska Regional Forecasts

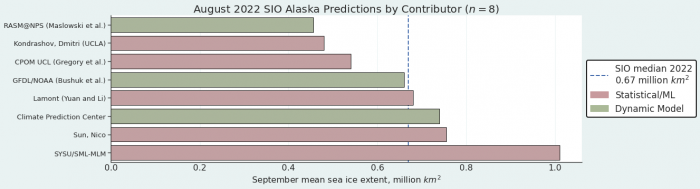

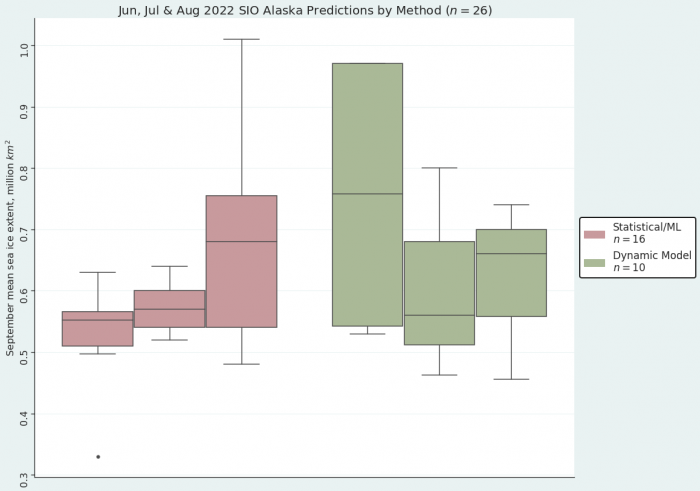

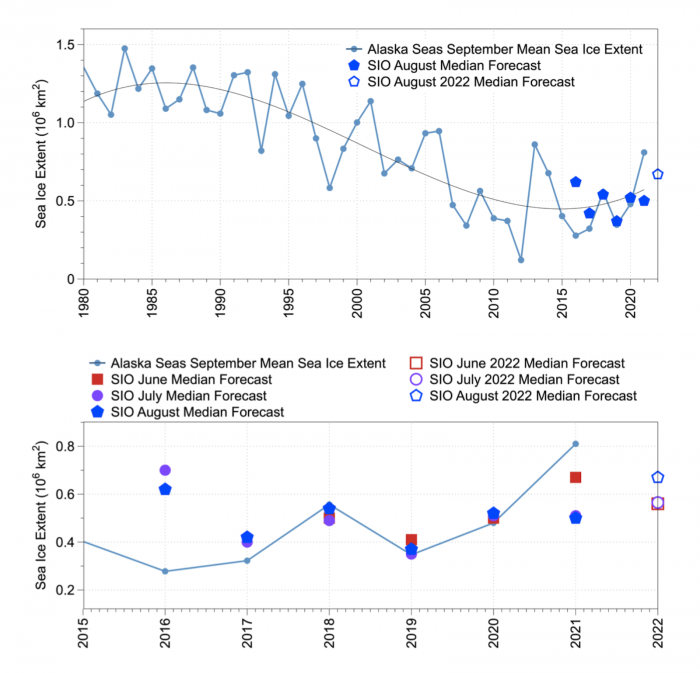

The multi-modal median for the August 2022 SIO forecast for the Alaska seas is 0.67 million square kilometers and consists of eight contributions with values ranging from 0.46 to 1.01 million square kilometers (Figure 4). The dynamical model forecasts range from 0.46 to 0.74 million square kilometers with a median of 0.66 million square kilometers. The statistical model forecasts range from 0.48 to 1.01 million square kilometers with a median of 0.68 million square kilometers. For the August SIO, the statistical forecasts display a larger spread (standard deviation of 0.19) compared to the dynamical models (standard deviation of 0.12; Figure 5). The spread in the dynamical models has decreased as the season progressed from June to August, whereas spread of statistical forecasts is greater in August than both June and July SIO contributions (Figure 5). To place these in historical perspective, the September median sea-ice extent for the averaged Alaska seas (Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort) over 2007–2021 is 0.40 million square kilometers (Figure 6, top), making the median August forecast for 2022 above all observed values between 2015 and 2020 (Figure 6, bottom). June–August SIO median forecasts were close to observations in 2018 through 2020, while the 2021 forecast was much lower than observed.

Pan-Arctic Forecasts with Spatial Methods

Sea Ice Probability (SIP)

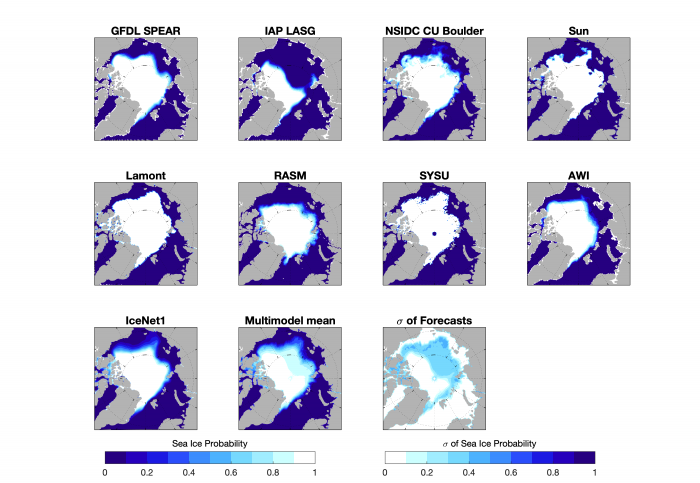

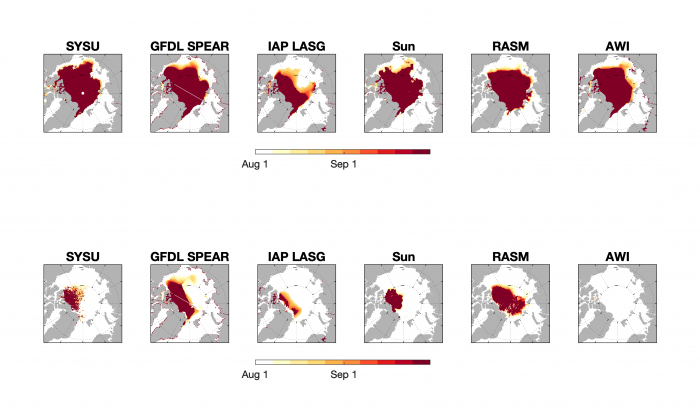

For August 2022, we have received nine forecasts of September sea-ice probability (SIP). There is, despite the relatively short lead time, considerable model spread, with some models forecasting very low SIP (e.g., IAP LASG), while others show high SIP throughout the Arctic ocean (e.g., Lamont, SYSU). Regionally, forecasts show good agreement in the European Arctic (east Greenland Sea, northern Barents/Kara seas), and in the eastern Beaufort. The main forecast uncertainty concerns sea-ice cover in the East Siberian sea, and the likelihood of survival of the area of sea ice that currently extends to the east Siberian coastline (see Figure 11 below).

Ice Free Date (IFD)

To a large degree, models show little melt between their August initializations and September (note the relatively small areas that are not white—melted out before forecast initialization, or dark red—do not melt out). IAP LASG is an exception, with significant areas of late-August IFD15 (melt below the 15% threshold), which likely helps explain its low SIP forecasts in Figure 7 above. As was seen in previous months, there is large uncertainty in IFD80 (melt below the 80% threshold) in the central Arctic ocean, with RASM and GFDL SPEAR showing large areas that do not melt below the 80% threshold; whereas, AWI is already below that threshold at initialization.

Antarctic Forecasts

The August round of forecasts for September mean Antarctic sea-ice extent is shown in Figure 9, together with the July and June forecasts. Similar to the previous forecasts, 2022 is anticipated to be a low year and possibly even a record one. Except for one outlier, all forecasts agree that the value for September will be below climatology. After the 2022 record low in February, it is thus likely that the annual mean of 2022 will also reach record low values.

Current Conditions

Pan-Arctic Conditions

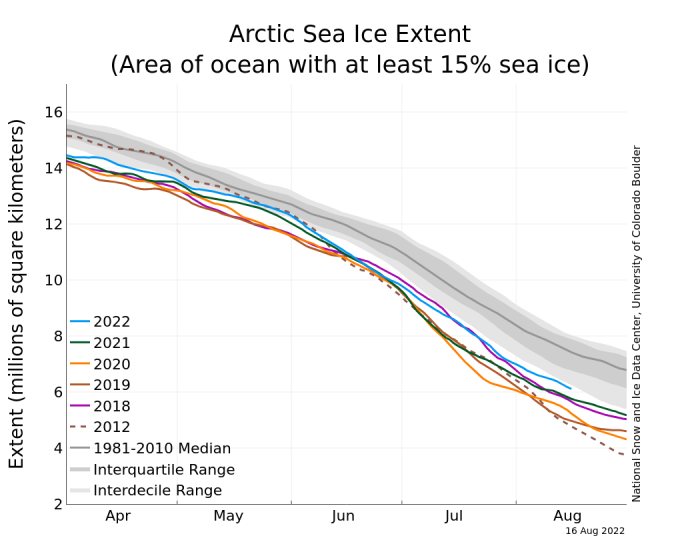

Based on data from the NSIDC Sea Ice Index, average Arctic sea-ice extent for July 2022 was 8.25 million square kilometers, ranking twelfth lowest in the 43-year satellite record. This was 1.22 million square kilometers below the 1981 to 2010 July average. The decline in extent during July was near the climatological average. By the beginning of August, the daily decline in extent usually begins to slow. The decline in 2022 has not slowed as much as usual and as of 15 August, the extent in 2022 was 6.16 million square kilometers, compared to the 1981–2010 15 August average of 7.42 million square kilometers (Figure 10). This is one of the highest mid-August sea-ice extents in the past decade.

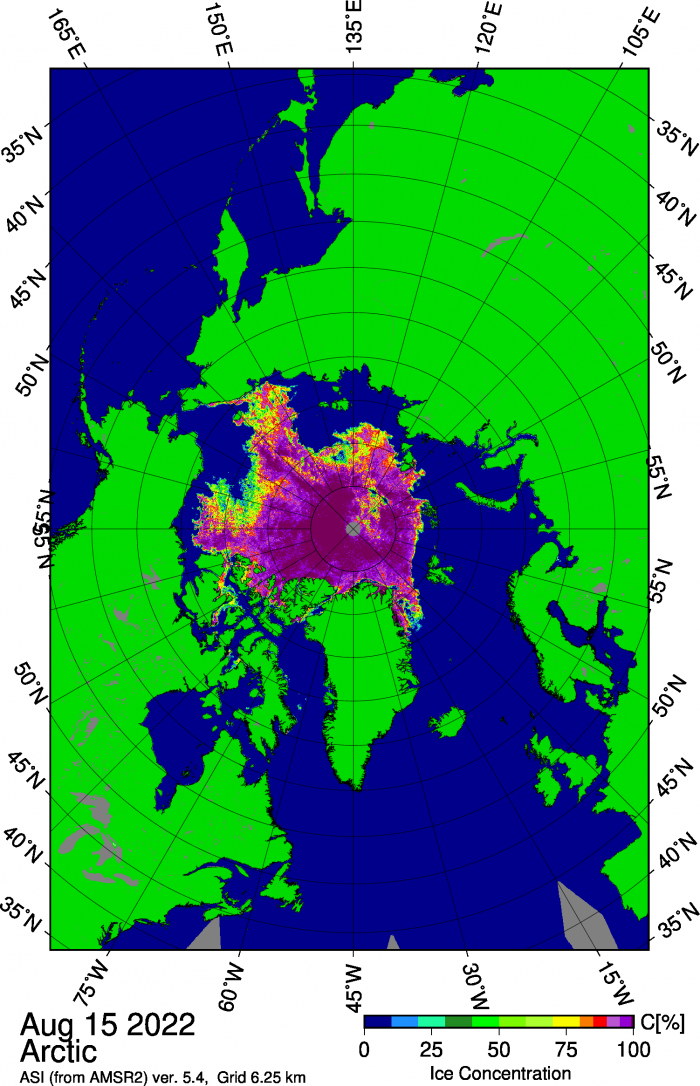

Nevertheless, as of mid-August, ice extent was lower than the 1981–2010 average in most sectors of the Arctic Ocean with the exceptions being the Beaufort Sea, where the ice edge was near normal, and most notably the East Siberian Sea, where ice still extended to the coast. A tongue of sea ice extending southward in the East Siberian Sea is not an uncommon feature, but the ice is particularly extensive in the region this year. By contrast, an area of low concentration ice and small areas of open water have persisted north of the Kara Sea, nearly to the pole (Figure 11).

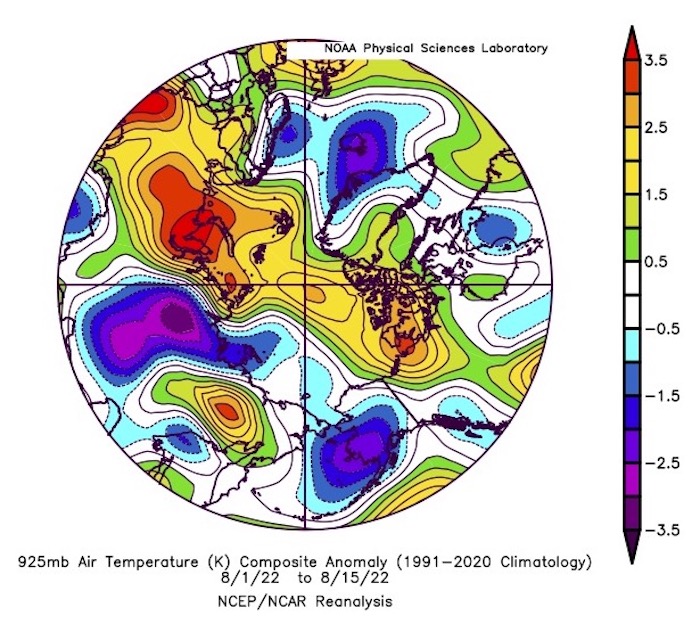

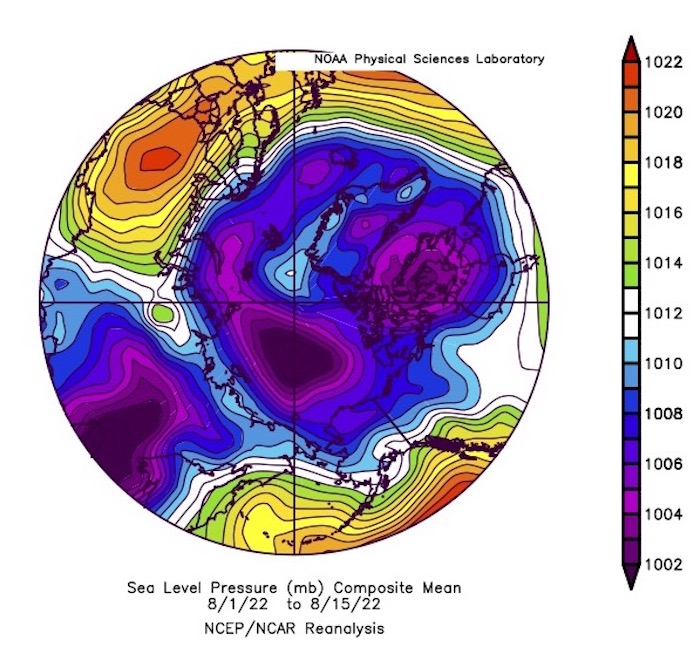

During the first half of August, air temperatures at the 925 hPa level (about 2,500 feet above the surface) were modestly above average from the Beaufort Sea across the pole and towards the Kara and Barents Seas (Figure 12). By contrast, temperatures over parts of the East Siberian and Laptev Seas as well as the southeastern Bering Sea were slightly below average. While air temperatures over the central Arctic Ocean were slightly above average, they are near the freezing point and freeze-up is likely already happening at the surface near the pole (the open water areas noted above will likely be gone soon). As for the atmospheric circulation, sea pressure as averaged over the first half of August featured low pressure over the central Arctic Ocean with multiple low centers, which is not uncommon at this time of year *Figure 13). Low pressure tends to result in cloudier skies and spreads out the ice, both of which can slow the decline in ice extent.

Alaska Regional Conditions

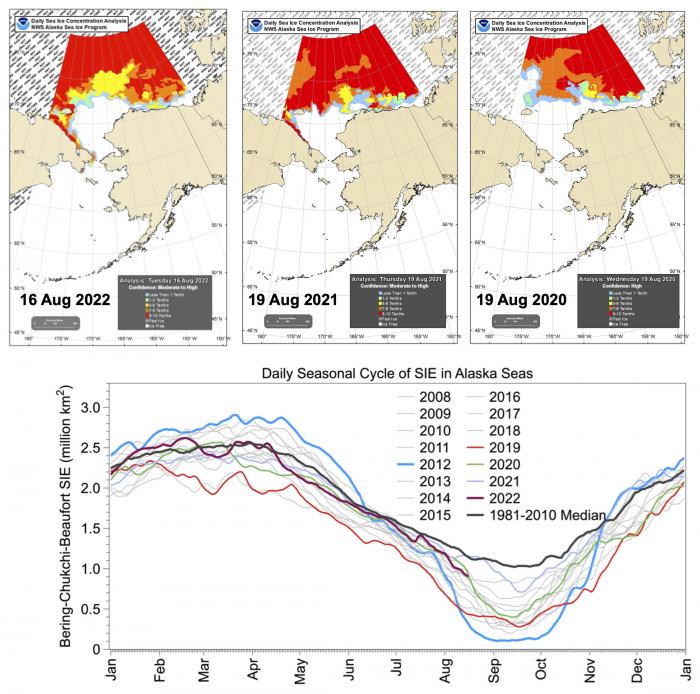

Mid-August 2022 sea-ice extent in the Chukchi Sea displays greater ice concentration, more ice along Chukotka, and more open water in the central Chukchi Sea compared to the 2022 mid-August conditions (Figure 14, top). In 2020, sea-ice concentration retreated farther north than 2022 or 2021. The eastern Beaufort has more sea ice in 2022 relative to 2021 or 2020. The combined Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort sea-ice extent since mid-April 2022 continues to be slightly lower than the 1981–2010 average (Figure 14, bottom). The retreat during mid-April to mid-May was faster than the long-term median, remained close to the median rate in June and July 2022, and has accelerated since mid-July to mid-August. The 15 August extent is 0.91 million square kilometers in 2022, which is below the 1981–2010 median value of 1.16 million square kilometers. The 15 August value for 2022 is below 2020 and 2021 values on the same day but above the 2019 value which was 0.44 million square kilometers (Figure 14, bottom). Sea-ice extent was lower in both the Chukchi (2022: 0.22 v.s. 2021: 0.39 million square kilometers) and Beaufort Seas (0.69 vs. 0.77 million square kilometers) on 15 August 2022 compared to the same day in 2021 based on the NSIDC data. The mid-July to mid-August rate of sea-ice extent decline in the Alaska seas was similar to that in 2019, but at a higher median sea-ice extent at this time. It is unlikely that the 2019 September mean extent will be surpassed in 2022 with a bit more than a month left in the melt season. However, the occurrence of a large weather event could strongly influence the minimum by enhancing ocean-ice melt and change the current trajectory to reach a lower minimum.

Ocean Heat Conditions

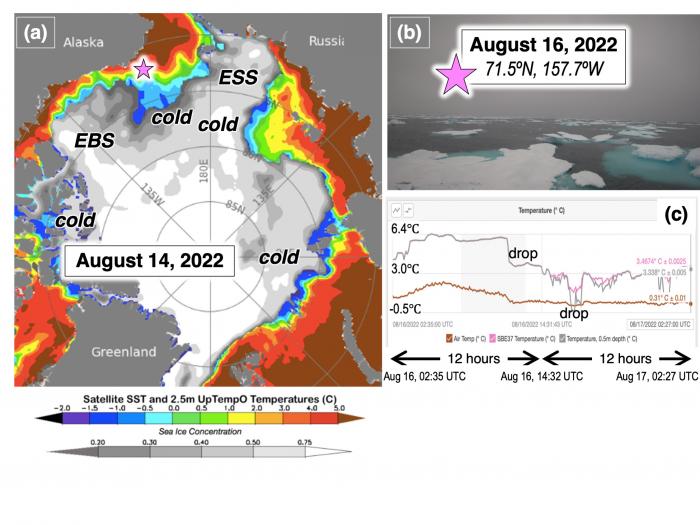

In mid-August 2022, open water sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the Arctic are generally warm in the south and cool or near-freezing cold in the north (Figure 15a). In particular, areas with active recent ice retreat (north of Alaska, northwest of the East Siberian Sea, and the northern Kara and northeastern Barents) are coldest, as the ocean gives up its heat to melt ice at this late stage of summer melting. Other areas (notably, the Eastern Beaufort Sea "EBS" and the East Siberian Sea "ESS") have retained substantial ice. If these melt out by the mid-September ice minimum, they will be quite cold and will likely freeze over quickly in early fall.

The pink star in Figure 15a marks the location of a Saildrone autonomous surface vehicle operated via NASA's MISST3 project (e.g., Vazquez-Cuervo et al. 2022) as it surveyed northwestward along the Distributed Biological Observatory's section DBO-5. Figure 15b shows that contrary to the satellite-derived passive microwave ice extent data, ice was present northwest of Point Barrow at this time. Even the NWS ASIP ice charts indicated open water in this area (Figure 15 top in this report), although the ice edge was quite close to the Saildrone's position. Further, the Saildrone SST data (Figure 15c) indicate cooling as it approached the ice, but still with above-freezing temperatures and warm values closer to the coast. The preliminary data thus indicate that low-concentration ice resides quite far south of the passive microwave ice edge at this time, and that above-freezing SSTs may also be present that are likely actively contributing to melting this sparse ice.

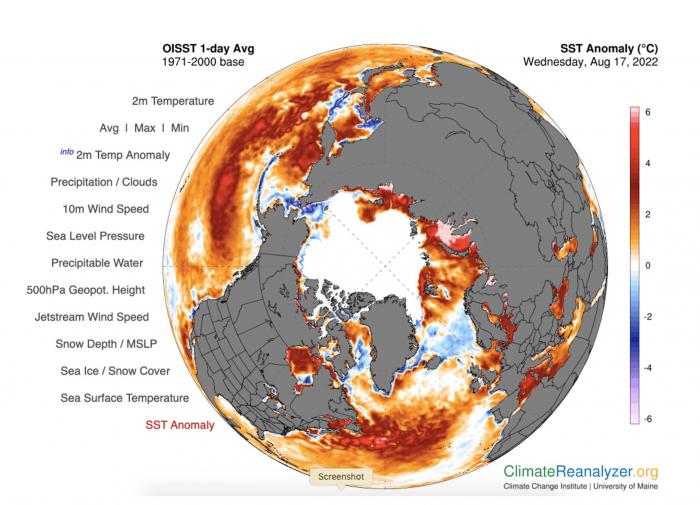

Pan-Arctic SST anomalies are presented in Figure 16. Alaskan Arctic SSTs are generally cooler than or near climatology, a result of the relatively late ice retreat this year. Meanwhile, SSTs on the Russian shelf from the northeastern Barents and eastward to the western ESS are quite anomalously warm. The cool/normal anomalies in the Norwegian Sea indicate that the Russian shelf warmth may be a result of early sea-ice retreat (relative to climatology), rather than advection of anomalously warm water from the south. However, this bears further study, since the southern Barents Sea is anomalously warm, and this area does participate in inflow to the Russian shelves.

References

Vazquez-Cuervo, J., S. L. Castro, M. Steele, C. Gentermann, J. Gomez-Valdes, and W. Tang. 2022. Comparison of GHRSST SST Analysis in the Arctic Ocean and Alaskan Coastal Waters Using Saildrones. Remote Sensing 14, https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14030692.

Contributor Key Statements, Summary of Uncertainties

![]() Summary Table of Key Statements from Individual Outlooks—per 30 August 2022 (PDF - 126 KB)

Summary Table of Key Statements from Individual Outlooks—per 30 August 2022 (PDF - 126 KB)

Contributor Full Report PDFs and Supplemental Material

This report was developed by the SIPN2 Leadership Team.

Report Lead:

Uma Bhatt, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Geophysical Institute

Additional Contributors:

Matthew Fisher and the NSIDC Development Team, Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder, NSIDC

Editors:

Betsy Turner-Bogren, ARCUS

Helen Wiggins, ARCUS

Kuba Grzeda, ARCUS

Stacey Stoudt, ARCUS

Lisa Sheffield Guy, ARCUS

Suggested Citation:

Bhatt, U.S., P. Bieniek, E. Blanchard-Wrigglesworth, H. Eicken, M. Fisher, L. C. Hamilton, J. Little, F. Massonnet, W. Meier, J.E. Overland, M. Serreze, M. Steele, J. Stroeve, J. Walsh, M. Wang, and H. V. Wiggins. Editors: Turner-Bogren, B., L., Sheffield Guy, J.K. Grzeda, S. Stoudt, and H. V. Wiggins. August 2022. "Sea Ice Outlook: 2022 August Report." (Published online at: https://www.arcus.org/sipn/sea-ice-outlook/2022/august.)

This Sea Ice Outlook Report is a product of the Sea Ice Prediction Network–Phase 2 (SIPN2), which is supported in part by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. OPP-1748308. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.