By: Ken Tape, University of Alaska Fairbanks

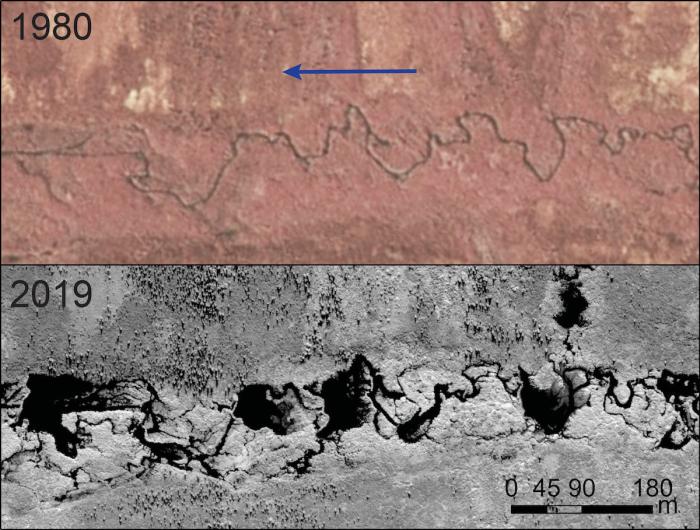

The Arctic tundra ecosystem of Alaska, and beyond, is changing under the influence of climate warming and other factors. Some of the more obvious landscape changes include increasing growth of shrubby vegetation and thawing permafrost. Shrub herbivores like moose and beavers have moved into the Arctic in the last century in response to an increase in their habitat, as well as reductions in hunting and trapping. Beavers are of particular interest because they rapidly alter lowland ecosystems by damming and engineering waterways, thus changing our conception of Arctic stream ecosystems from free-flowing narrow watercourses to dynamic beaver ponds and wetlands. Using satellite imagery, we mapped 13,000 beaver ponds in tundra regions of northwest Alaska, and most of these areas have witnessed a doubling in ponds from 2003 to 2017. These beaver ponds increase unfrozen water, thaw permafrost, and seem to create oases of warmth, heterogeneity, and biodiversity. Ultimately, where beaver habitat exists, we will need to reenvision Arctic tundra stream and riparian ecosystems from free-flowing streams and sloughs to dynamic wetlands engineered by beavers. Many of these changes have been observed with interest and concern by people in remote communities across northwestern Alaska and northern Canada.

The Arctic Beaver Observation Network (A-BON), is a group of scientists, Indigenous groups, land managers, and local observers who are concerned about the expansion of beaver populations into Arctic landscapes. This collaboration, funded by NSF's Office of Polar Programs (Award Abstract # 2114051), began in 2020 and assembles a broad range of perspectives from circumarctic nations to coordinate research and observations related to beaver colonization of the Arctic and the impacts it is having on ecosystems and people. The first A-BON meeting, convened in March 2022, was held virtually and hosted in Fairbanks, Alaska. The second A-BON meeting was November 2022 in Yellowknife, Northwest Territory, and focused more on Indigenous concerns associated with fish, as well as viable management strategies. An in-person meeting in Fairbanks, Alaska is planned for 26–28 February 2024 and will bring together perspectives from research, Indigenous Knowledge, and resource management.

Major projects studying this new phenomenon are underway in Alaska (A-BON) and in Canada through the associated project, Beavers and Socio-ecological Resilience in Inuit Nunangat (BARIN), led by Helen Wheeler at Anglia Ruskin University. These projects include fieldwork, remote sensing, and knowledge co-production with Indigenous communities. The research aspects address questions about the myriad impacts of beaver engineering in the Arctic, with a focus on the impacts that are unique to high-latitude environments, such as the presence of permafrost. Scientists are also examining where beaver colonization is occurring and when it might reach other tundra regions, which requires a better understanding of what is limiting their current expansion. Though few studies have been completed at this point, initial results indicate that the thousands of new beaver ponds in tundra regions exacerbate the effects of climate change and impact almost all aspects of stream and riparian ecosystems, from fish and water quality to permafrost hydrology and biodiversity.

Knowledge co-production is occurring in remote communities stretching from Hudson Bay across northern North America to western Alaska. Some of the major concerns about nascent beaver engineering relate to fish movement and water quality, though initial interviews indicate that not all people view the newcomers as something negative, emphasizing the subsistence value of the fur and meat. The blending of ideas borne of western science and traditional knowledge has been enlightening, because the different perspectives tend to be complementary, filling gaps in the other's understanding. The Arctic Beaver Observation Network is coordinating research approaches, local knowledge, and management to place these nascent engineering changes within the breadth of the changes already underway in the Arctic environment.

For further reading, see "As Beavers Gain Foothold in Arctic Alaska, Some See Benefits in How They Reshape the Landscape"

About the Author

Ken D. Tape is a Research Professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks whose expertise is in Arctic ecology. His research interests include climate change and the impacts of 20th century climate warming on various components of the Arctic ecosystem, including vegetation, permafrost, hydrology, and wildlife.

Ken D. Tape is a Research Professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks whose expertise is in Arctic ecology. His research interests include climate change and the impacts of 20th century climate warming on various components of the Arctic ecosystem, including vegetation, permafrost, hydrology, and wildlife.