By Mead Treadwell

Over the two-year official period of the fourth International Polar Year (IPY), from March 2007 to March 2009, scientists from more than 60 nations carried out over 160 IPY projects, supported by approximately $1.2 billion, mostly from national scientific agencies. Although its full scientific legacy will evolve over the coming years, it was clear as IPY came to its successful close in early 2009 that the program had made valuable progress toward the four major goals set by the International Council for Science (ICSU) IPY planning group in 2004:

- advances in polar knowledge and understanding;

- a legacy of improved observational systems, facilities, and infrastructure;

- new generation of polar scientists and engineers; and

- interest and participation from polar residents, students, the public, and decision-makers.

U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton delivers opening remarks at the Joint Session of the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting and the Arctic Council in April 2009. In her speech, Clinton declared a U.S. commitment to a "high level of engagement with our partners" on arctic policy and to ratifying the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which will help resolve disputed maritime borders in the Arctic Ocean. To Clinton's right are Jonas Gare Støre, Norwegian Foreign Minister and Arctic Council chair, and John Holdren, Director of the U.S. Office of Science and Technology Policy. Photo credit: Tim Sloan/AFP/Getty Images.

Significantly, IPY has made impressive progress with the last goal—educating the public and decision-makers. As a variety of high profile events and publications shared some of the program's early scientific results, it became increasingly obvious that national and international policy-makers and the public are beginning to recognize the Arctic's scientific and strategic importance. From international diplomatic events to presidential policy changes and increased science budgets, the events of the past few months show that arctic science no longer operates in obscurity. In this new era of arctic awareness, it is incumbent on the members of the research community to be prepared—both to maximize the many opportunities the new era brings and to think through the policy implications of their work.

Ministerial Declaration on IPY

In April, the Member States of the Arctic Council and the Consultative Parties to the Antarctic Treaty met for the first time in Washington DC.

In her welcoming remarks, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton called for increased attention to the Arctic to "strengthen peace and security, support sustainable economic development, and protect the environment." Following diplomatic meetings at the U.S. State Department, the joint polar event celebrated the accomplishments of IPY with a seminar hosted by NSF and the U.S. National Academy of Sciences Polar Research Board.

The more than 400 diplomats at the event issued a Ministerial Declaration on the IPY and Polar Science, urging cooperation and support to deliver a lasting legacy from the IPY. The text of the ministerial declaration is available on the State Department website, and video of the IPY seminar is available on the NSF website.

Later in April, diplomats gathered at the Sixth Ministerial Meeting of the Arctic Council in Tromsø, Norway, where they discussed ways to integrate results from IPY into the council's ongoing projects. The ministers also signed the Tromsø declaration, which "recognize[d] the urgent need for an effective global response that will address the challenge of climate change, and confirm[ed] the commitment of all Arctic States to actively contribute to reaching an adequate agreed outcome at the [UN Framework Convention on Climate Change] 15th Conference of the Parties in Copenhagen in December 2009."

IPY Raises Arctic Visibility

"IPY research has advanced frontiers in fields that range from climate science to understanding the mechanics of the world's great ice sheets to the sociological ramifications of unprecedented changes occurring in the Arctic….Researchers from the U.S. and more than 60 other nations have built a knowledge base that will elucidate our actions deep into the next century."

- —Arden Bement, National Science Foundation

- Address at A Celebration of the International Polar Year

"The International Polar Year has stimulated an intense focus on the Arctic. The number and capability of modern research tools that are in, around, or above the Arctic, the skills of the observers and the modelers, and the international cooperation exceed any deployment, in any ocean, to date."

- —David Carlson, IPY International Programme Office

- Testimony before the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee

"In a relatively short period of time fundamental changes have occurred in relation to the circumpolar North.....[T]he perception of the Arctic as a globally important region in biophysical and geopolitical terms has taken hold. To a significant degree, this perception has been fuelled by a growing awareness of the extensive impacts on the Arctic of changes in climate and climate variability."

- —Senior Arctic Official Report to Ministers

- Arctic Council, Tromsø

Also noteworthy at the Tromsø meeting was a decision to form a task force on short-term forcers of arctic climate change, including methane and black carbon. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is helping to lead the task force, and ideas from the science community to help reduce these pollutants, which promote amplification of temperatures in the Arctic, would be helpful. The task force's goals could benefit from research on methods to convert agricultural waste to energy, better coordinate boreal forest wildfire management, and collect and burn methane that would otherwise be released into the atmosphere.

Senate Hearing on Arctic Warming

Following on the Arctic Council meeting, the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, chaired by Senator John Kerry (D-MA), held a roundtable hearing on the Global Implications of Arctic Warming in May 2009. The session included:

- Scott Borgerson of the Council on Foreign Relations on strategic governance of the Arctic Ocean;

- Lawson Brigham on the Arctic Council's newly released Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment (AMSA; available online; see Witness Spring 2006);

- David Carlson of the IPY International Programme Office on implications of early findings from IPY research projects;

- Lisa Speer of the Natural Resources De-fense Council on high seas fisheries; and

- myself on the value of international scientific cooperation in the Arctic.

All five of us stressed the importance of making progress on:

- ratifying the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), still pending in the Senate,

- building new U.S. icebreakers, and

- ensuring greater stability in U.S.-Russian cooperation on arctic research.

Following on the findings and recommendations of AMSA, we noted that although arctic governments are already moving forward to improve Arctic Ocean ship standards and search and rescue in the Arctic, the Arctic Ocean is still not fully accessible to science, and UNCLOS could make it even less so. We need to continue to strive for improvements to this situation—too much of what's happening in the world climate scene depends on knowledge of arctic processes, and knowledge of arctic processes depends on ocean access.

New USARC Goals Report

As this newsletter goes to press, the U.S. Arctic Research Commission (USARC) is completing its 2009 Goals Report for the U.S. Arctic Research Program. In the past two years we have seen considerable progress within the Interagency Arctic Research Policy Committee (IARPC), chaired by NSF Director Arden Bement, on development of research plans, including new cross-cutting efforts on:

- arctic infrastructure, led by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers,

- arctic resource assessment, led by the U.S. Geological Survey,

- arctic health, led by the National Institutes of Health, and

- preservation of indigenous languages, identities and cultures.

The USARC report also identifies ways to continue strengthening research efforts on arctic climate and in the Bering Sea and Arctic Ocean, including:

- making progress in defining the national/international Sustained Arctic Observing Network (SAON);

- incorporating arctic research needs in any revision of the nation's climate change science or climate change technology programs;

- close accounting and modeling of feedbacks from arctic gas hydrates and permafrost organic materials in any global greenhouse gas mitigation regime; and

- advancing arctic adaptation research.

Finally, we are pleased to announce that the USARC is detailing an experienced arctic scientist—Kate Moran of the University of Rhode Island—to the Office of Science and Technology Policy to advance the provisions of the 1984 Arctic Research and Policy Act.

In summary, the arctic science community should be very pleased with the improved awareness of the Arctic that IPY has helped bring to policy-makers and the public—but we cannot pause to savor this advance for long. We must work together to take full advantage of the progress we have made and use it to address the many critical problems our research has identified.

Mead Treadwell was appointed to the USARC in 2001 and designated chair by President Bush in 2006. Treadwell also serves as Senior Fellow of the Institute of the North, where his research focuses on strategic and defense issues, management of commonly owned resources, and integration of transport and telecommunications infrastructure. For more information, see the USARC website or contact Treadwell at meadwell [at] alaska.net.

IPY Publications Highlight Early Results, Remaining Challenges

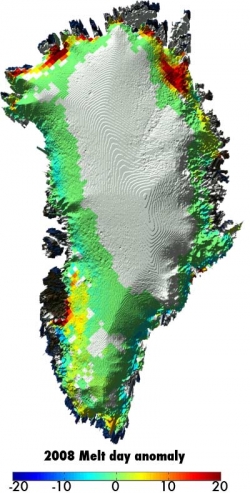

Figure: Extreme snowmelt during summer 2008 over the northern part of the Greenland ice sheet, based on the analysis of microwave data recorded by the Special Sensor Microwave Imager (SSM/1) on the F13 satellite of the U.S. Defense Meteorological Satellite Program. Colors indicate the 2008 melt day anomaly for Greenland (number of days in 2008 with surface melt minus the average for 1979–2007). Reprinted from The State of Polar Research, courtesy M. Tedesco, CUNY/NASA/UMBC.

In February 2009, the international committee overseeing IPY released a report highlighting early results and calling on participating nations to ensure that the momentum generated by the program carries into sustained support for polar research in the future. Developed by the ICSU/World Meteorological Organization (WMO) Joint Committee for IPY, The State of Polar Research received international media attention, citing new findings that rapid polar changes will affect global systems. "The International Polar Year 2007-2008 came at a crossroads for the planet's future," said WMO Secretary-General Michel Jarraud at the report's launch, "The new evidence resulting from polar research will strengthen the scientific basis on which we build future actions." The report outlines some of the new findings in arctic research that have emerged from IPY, including:

- Novel techniques used to assess mass balance of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets indicate that both are losing mass and contributing to rising sea levels (see figure). The potential for further rapid ice discharge from these regions remains a major unknown in projecting rate of sea level rise. Modelers expect, however, that new data collected by collaborative IPY surveys and traverses of the ice sheets will help strengthen their predictions.

- Sea ice extent in the Arctic Ocean reached a record minimum in September 2007, and the percentage that was relatively thin first year ice continued to increase.

- The types and extents of vegetation in the Arctic have changed substantially in response to warming, including transitions from grasses to shrubs, shifts in treeline, and modification of soil structure. These landscapes changes are affecting the larger ecosystems and their human users.

- Estimates of carbon trapped in permafrost are higher than previously calculated, and new evidence suggests that terrestrial permafrost degrades much faster than expected as sea ice disappears. Cruises along the Siberian coast observed substantial out-gassing of methane from thawing ocean sediments.

In addition, a special section in the 26 February 2009 issue of Nature celebrated the achievements of IPY, but an editorial cautioned that those achievements must be exploited to the fullest by maximizing the effectiveness of the IPY data management system, organizing an effective assessment of the findings for use by decision-makers and the public, and creating ongoing observation networks at both poles. Efforts are underway on all three of these fronts, but all will need substantial international support and cooperation.

<

p>The State of Polar Research is available on the IPY International Programme Office website. The Nature editorial on IPY is available online.

U.S. Policy Revisions Reflect Arctic Warming

In 2007, the USARC proposed a review of U.S. arctic policy, last updated in 1994. The National Security Council and Department of State led an interagency process that culminated in President Bush issuing a new presidential directive in January 2009. The revised arctic policy takes into account several developments, including:

- Altered national policies on homeland security and defense;

- The effects of climate change and increasing human activity in the region;

- The establishment and ongoing work of the Arctic Council; and

- A growing awareness that the region is both fragile and rich in resources.

The new policy seeks to:

- Meet national and homeland security needs relevant to the arctic region;

- Protect the arctic environment and conserve its biological resources;

- Ensure that resource management and economic development in the region are environmentally sustainable;

- Strengthen institutions for cooperation among the eight arctic nations;

- Involve indigenous communities in decisions that affect them; and

- Enhance scientific monitoring and research into local, regional, and global environmental issues.

Below, the policy on scientific cooperation is reproduced in its entirety, and two sections relevant to the scientific community are summarized.

International Scientific Cooperation

- Scientific research is vital for the promotion of U.S. interests in the arctic region. Successful conduct of U.S. research in the arctic region requires access throughout the Arctic Ocean and to terrestrial sites, as well as viable international mechanisms for sharing access to research platforms and timely exchange of samples, data, and analyses. Better coordination with the Russian Federation, facilitating access to its domain, is particularly important.

- The U.S. promotes the sharing of arctic research platforms with other countries in support of collaborative research that advances fundamental understanding of the arctic region in general and potential arctic change in particular. This could include collaboration with bodies such as the Nordic Council and the European Polar Consortium, as well as with individual nations.

- Accurate prediction of future environmental and climate change on a regional basis, and the delivery of near real-time information to end-users, requires obtaining, analyzing, and disseminating accurate data from the entire arctic region, including both paleoclimatic data and observational data. The U.S. has made significant investments in the infrastructure needed to collect environmental data in the arctic region, including the establishment of portions of an arctic circumpolar observing network through a partnership among U.S. agencies, academic collaborators, and arctic residents. The U.S. promotes active involvement of all arctic nations in these efforts in order to advance scientific understanding that could provide the basis for assessing future impacts and proposed response strategies.

- U.S. platforms capable of supporting forefront research in the Arctic Ocean, including portions expected to be ice-covered for the foreseeable future, as well as seasonally ice-free regions, should work with those of other nations through the establishment of an arctic circumpolar observing network. All arctic nations are members of the Group on Earth Observations partnership, which provides a framework for organizing an international approach to environmental observations in the region. In addition, the U.S. recognizes that academic and research institutions are vital partners in promoting and conducting arctic research.

- Implementation: In carrying out this policy as it relates to promoting scientific international cooperation, the Secretaries of State, the Interior, and Commerce and the Director of the National Science Foundation, in coordination with heads of other relevant executive departments and agencies, shall:

- Continue to play a leadership role in research throughout the arctic region;

- Actively promote full and appropriate access by scientists to arctic research sites through bilateral and multilateral measures and by other means;

- Lead the effort to establish an effective arctic circumpolar observing network with broad partnership from other relevant nations;

- Promote regular meetings of arctic science ministers or research council heads to share information concerning scientific research opportunities and to improve coordination of international arctic research programs;

- Work with the Interagency Arctic Research Policy Committee (IARPC) to promote research that is strategically linked to U.S. policies articulated in this directive, with input from the Arctic Research Commission; and

- Strengthen partnerships with academic and research institutions and build upon the relationships these institutions have with their counterparts in other nations.

Security Interests

Recognizing that the Arctic is primarily a maritime domain and that human activity in the region is increasing, the U.S. should:

- Assert a more active and influential presence to protect its arctic interests and to project sea power throughout the region;

- Increase arctic maritime domain awareness in order to protect commerce, critical infrastructure, and key resources;

- Preserve the global mobility of U.S.

vessels and aircraft throughout the region; and - Project a sovereign U.S. maritime presence in the Arctic in support of essential U.S. interests.

Governance and Boundary Issues

Although the policy supports U.S. participation in international organizations such as the Arctic Council, it does not endorse an "Arctic Treaty" along the lines of the Antarctic Treaty.

Given the region's unresolved maritime boundaries, the policy urges:

- The U.S. Senate to accede to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS);

- Federal agencies to establish the outer limit of the U.S. continental shelf; and

- Russia to ratify the 1990 U.S.-Russia maritime boundary agreement.