By: Rick Thoman, Climate Specialist with the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy; and Jacqueline Richter-Menge, Arctic Report Card Editor

The 15th annual NOAA Arctic Report Card was released on 8 December 2020 as part of the American Geophysical Union 2020 Fall Meeting. This year, 134 authors from 15 counties volunteered their time and expertise to help create the report card. The Arctic Report Card (ARC) is not a collection of scientific papers. Rather, the editors work with the authors to craft essays that are concise and written with a broad audience in mind, making the report a useful resource for anyone with interest in Arctic matters. One of the strong points of the report card is the breadth of subject matter. This makes it an excellent resource to get quick, up-to-date information on how the many parts of the Arctic system—physical, biological, and human—are affecting and being affected by the myriad of interconnected changes. In addition to the collection of essays, the ARC communications team creates a website and a professional quality video, and works with AGU to host the roll-out every December. This year, a new online ARC-specific data portal was developed in partnership with the NSF Arctic Data Center to provide ready access to most of 27 datasets that inform key findings within ARC 2020's reporting.

The organization of this year's report card is quite similar to previous editions: 16 essays are grouped into Vital Signs, Indicators, and Frostbites. Vital Signs are reported on annually, and include air and sea surface temperatures, the Greenland Ice Sheet, terrestrial snow, tundra greenness, and primary ocean productivity. Indicators provide updates on other aspects of the Arctic environmental system that are better suited to a less-than-annual frequency due to availability of data. This year, the report card includes an update to glaciers and ice caps outside of Greenland for the first time since 2013 and a reprise of the 2017 essay on high-latitude wildfire. Bowhead whales, last featured in the 2012 report card, have been a staple food resource for millennia. A changing Arctic has both positive and negative impacts to this critical and iconic specialist of the icy oceans. Coastal, land-based permafrost is introduced as a new topic, emphasizing the recent rapid increase in erosion rates coinciding with warming air temperatures, sea-ice reduction, and permafrost thaw. This year's Frostbites essays focus on observations of Arctic change, including the historic 2019–20 MOSAiC expedition and the recent opening of NOAA's new and improved Barrow Observatory near Utqiaġvik, which will permit the continuation of half a century of in situ terrestrial observations and support new research (Figure 1). You'll also find essays on how observations have increased the accuracy and utility of climate models, and how the observations themselves have led to increased understanding of the physical processes in the Arctic over the lifetime of the ARC.

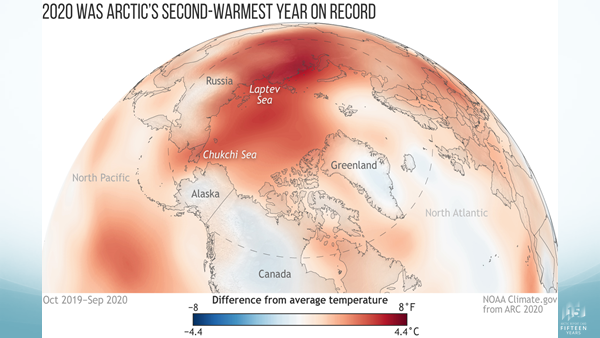

The 12-month period of October 2019 through September 2020 was the second-warmest on record (since 1900) for the Arctic, driven by the extreme high temperature departures over the high Arctic and Siberia (Figure 2). These conditions led to early snowmelt, which supported extensive high-latitude wildfires of the Eurasian taiga and tundra. The minimum sea-ice extent in 2020 was also the second lowest in the 42-year satellite record, with very early ice loss north of the Siberian coast contributing to the near-record warm air temperatures in the region. While the September sea-ice minimum typically gets the spotlight, changes in the thickness, quality, timing, and seasonality of the sea-ice cover also impact everything from the ecosystem, to coastal communities, to commercial shipping, and to national security. August 2020 average sea surface temperatures were ~1–3°C warmer than the 1982–2010 August mean over most of the Arctic Ocean, with exceptionally warm sea surface temperatures in the Laptev and Kara seas in August 2020 coinciding with the early loss of sea ice in this region. Also tied to sea ice and ocean temperature conditions is productivity at the bottom of the marine food web. During July and August 2020, the Laptev Sea of the Eurasian Arctic showed much higher primary productivity (~2 times higher for July and ~6 times higher for August) than the same months of the 2003–2019 multi-year average. Like so much else in our lives, the COVID-19 pandemic altered the 2020 report card. A planned essay on impacts of the changing Arctic to marine subsistence activities from the viewpoints of Indigenous experts from two northwest Alaska communities. But because of COVID-19, this had to be postponed to a future report card due to travel and community-related exposure restrictions.

The 15-year history of the Arctic Report Card is reviewed by Jackie Richter-Menge, who served in an editorial capacity for every issue. The report card, initiated in response to the need for concise and timely Arctic information, now serves as a readily available resource for viewing the rapid changes that have engulfed the region. Taken as a whole, the story is unambiguous. The transformation of the Arctic to a warmer, less frozen, and biologically changed region is well underway.

About the Authors

Rick Thoman is an expert in Alaska climate and weather with the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy (ACCAP). He produces reliable Alaska climate change information and graphics describing Alaska's changing environment. His work spans the bridge between climate modeling, Alaska communities, and media.

Rick Thoman is an expert in Alaska climate and weather with the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy (ACCAP). He produces reliable Alaska climate change information and graphics describing Alaska's changing environment. His work spans the bridge between climate modeling, Alaska communities, and media.

Jackie Richter-Menge's research activities focus on developing a more comprehensive understanding of the Arctic sea-ice cover, providing observations that can be used to advance forecasts in support of near real time operational needs and future projections associated with global climate variability. She helped conceive the Arctic Report Card, motivated by the need for more timely communication to a broad audience about the impact of warming global temperatures on the Arctic environment.

Jackie Richter-Menge's research activities focus on developing a more comprehensive understanding of the Arctic sea-ice cover, providing observations that can be used to advance forecasts in support of near real time operational needs and future projections associated with global climate variability. She helped conceive the Arctic Report Card, motivated by the need for more timely communication to a broad audience about the impact of warming global temperatures on the Arctic environment.