In a recent survey of the U.S. general public, a team of researchers led by Lawrence Hamilton at the University of New Hampshire’s Carsey Institute investigated the correlation between climate beliefs and the assimilation of science information. This research, funded in part by NSF, found complex patterns in which perceptions about arctic trends could sometimes be a consequence of general beliefs rather than a simple function of science literacy. These findings have implications for science education and outreach efforts, which often aim to communicate the basic information that underlies scientific conclusions.

Hamilton and colleagues designed the survey, whereby telephone interviews were conducted with a nationwide random sample of 2,000 people in the summer of 2011. Questions covered respondent background and opinions on various topics, along with some climate belief or knowledge items like the arctic sea ice question below. To avoid possible bias, interviewers rotated the order in which they read response choices. Comparisons between the survey and 2010 U.S. Census data allowed weighting for representative results. A series of statewide New Hampshire surveys, asking the same questions, also support the national conclusions.

The survey investigated public knowledge of arctic sea ice facts with the following question:

Which of the following three statements do you think is more accurate?

Over the past few years, the ice on the Arctic Ocean in late summer:

1. Covers less area than it did 30 years ago.

2. Declined but then recovered to about the same area it had 30 years ago.

3. Covers more area than it did 30 years ago.

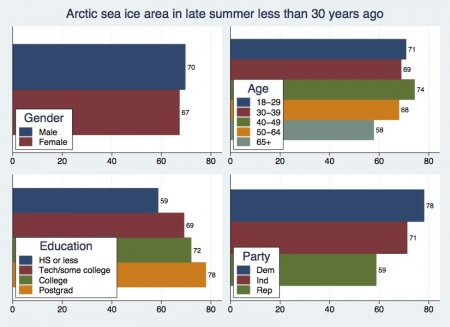

Sixty-eight percent of the survey respondents knew that sea ice area has declined. The remaining 32%, however, thought that ice has recovered, or covers more area, or said they did not know. Although 68% nationally think that late-summer arctic sea ice area has declined compared with 30 years ago, this fraction is not constant across sub-groups. There are weak but statistically significant correlations with gender and age (See Figure 1), however, education and political party exhibit stronger effects on what people think about arctic sea ice. This is also true in regards to other science and environment topics.

From a social-science perspective, wrong answers proved to be as interesting as right answers. Correct answers can be predicted by education and some wrong answers have predictors that suggest a lack of knowledge, but other wrong answers are predicted by political and belief factors instead. Researchers found that response to the sea ice question also correlated with general beliefs about climate change, which was assessed by another question on the survey:

Which of the following three statements do you personally believe?

1. Climate change is happening now, caused mainly by human activities.

2. Climate change is happening now, but caused mainly by natural forces.

3. Climate change is NOT happening now.

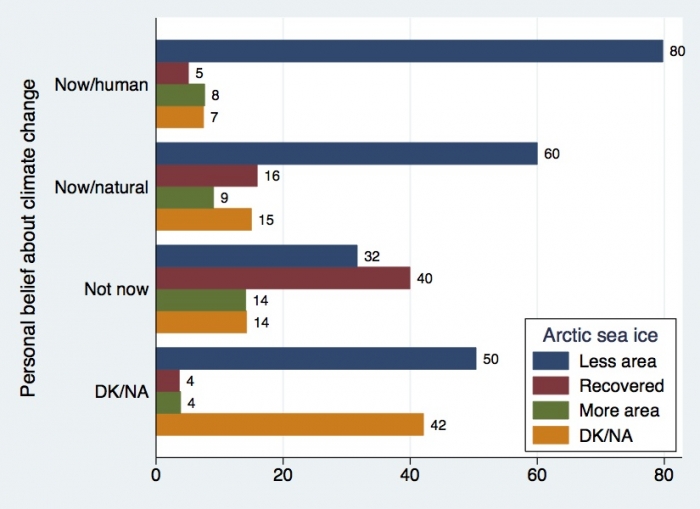

Figure 2 shows that arctic sea ice decline was known or guessed by 80% of those who believe climate is changing now due to humans, 60% of those who believe it is changing but for natural reasons, and just 32% of those who believe climate change is not happening now. The "not now" respondents were eight times more likely than "now/human" respondents to think that arctic ice has recovered. The "not now" group was even less accurate than those who simply said they do not know about climate change, which is a pattern replicated on other questions and surveys.

The knowledge/belief relationship graphed in Figure 2 might be interpreted as a "science literacy" effect, which assumes that knowing about arctic ice decline (and similar facts such as CO2 rise) makes people more prone to accept the scientific consensus on human-caused climate change. However, causality also runs in the opposite direction, from general beliefs to whether or not people credit scientific results. A process called biased assimilation, or selectively retaining information that supports pre-existing beliefs, could shape acceptance of the false but widely publicized claim that arctic sea ice has recovered. Detailed analyses in the study suggest that biased assimilation partly explains the patterns in Figure 2.

Regarding science outreach efforts, Hamilton notes that an information-to-conclusion ordering, which follows the natural logic of science, may not be successful in affecting public opinion on politicized topics where biased assimilation works in the opposite direction. Alternative approaches that identify and address prevalent misinformation may be more appropriate.

The 2011 national survey was supported by a grant from the Ford Foundation. Building on these results, newer statewide surveys continue tracking perceptions about polar regions in connection with the PoLAR Climate Change Education Partnership (supported by NSF).

For further information about the analysis of the patterns behind public perceptions of sea ice, please see: Did the Arctic ice recover? Demographics of true and false climate facts. Or contact Lawrence Hamilton (Lawrence.Hamilton [at] unh.edu).

References

Hamilton, Lawrence C. 2012. Did the Arctic ice recover? Demographics of true and false climate facts. 2012. Weather, Climate, and Society. DOI: 10.1175/WCAS-D-12-00008.1.