Introduction

Since 1976, social anthropologist and ethnographer Ann Fienup-Riordan has worked in southwest Alaska documenting traditional Yup'ik knowledge of communities in the Bering Sea coastal area and delta system of the lower Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers. Her recent work aims to conceptualize the Bering Sea ecosystem in Alaska Native terms and is part of the Integrated Bering Sea Project (see Witness, Fall 2010).

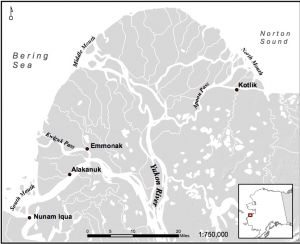

The use of ethnography for her work in the village of Emmonak provides a framework for investigating Yup'ik concerns about the changes in climate and ecology occurring along the Bering Sea coast.

Ethnography is a qualitative research method of gathering and synthesizing empirical data on human societies and cultures. Data collection often combines participant observation, field notes, interviews, questionnaires, and archival research. Instead of viewing a community's response to environmental and economic changes as a function of fixed cultural norms, the ethnographic perspective helps researchers understand how people continually reshape their lives in the course of everyday experiences.

Working in coordination with the staff of a regional non-profit organization, the Calista Elders Council, including Yup'ik language translator Alice Rearden, Fienup-Riordan's recent work pioneered a topic-specific format for documenting traditional knowledge. Small groups of elder experts, accompanied by younger community members, are gathered to address a specific set of questions. These sessions last two to three days and always take place in the Yup'ik language. Similar to academic symposia, this format encourages elders to speak among peers as topic experts. These topic-specific gatherings create a context for cultural transmission in which elders share the qanruyutet (words of wisdom) that guide their interactions with the environment.

Fienup-Riordan's ethnography of the village of Emmonak draws on observations from topic-specific gatherings on the Yukon delta during 2011, results of previous survey and interview work, and historical information. Her work illuminates the social and economic conditions facing many coastal Alaska communities today and provides perspective for understanding the ways in which marine ecosystems matter to these communities.

The Ethnographic Story of Emmonak

The village of Emmonak, with a population of 750, faces significant challenges today. These are exemplified by the harsh conditions of 2009 in which the foundation of the local economy, commercial king salmon fishing, crashed; severe cold weather prevented fuel delivery; and subsequent escalating fuel costs for heat and transportation created economic crises for many households. Unfortunately, these hardships are not uncommon.

The community's history helps provide context for current conditions. Starting in the late 1800s contact with non-native people had significant impact on communities along the lower Yukon River. Barged supplies for new settlements were landed at St. Michael to be shipped up the Yukon and non-natives moved to the Yukon delta to exploit the salmon fishery, building canneries and stores at central locations. With a cash economy and easier access to western goods, contact also brought epidemic diseases. During both the 1900 and 1918 influenza pandemics whole villages were wiped out. Orphans gathered at the Catholic Mission just south of present day Emmonak. At the mission children learned English, which in adulthood they spoke to their own children, breaking the strength of the Yup'ik language. Even with these changes, families continued to live scattered in hundreds of seasonal camps, comprised of one to a dozen households. In the early 1960s, however, the Bureau of Indian Affairs built schools at central locations like Emmonak. The law required parents to send their children to school and people abandoned their winter camps and moved into town.

People did not, however, abandon use of subsistence resources. Emmonak residents are heavily dependent on local harvests, annually averaging 510 pounds per person compared to 23 pounds per person for urban Alaska, according to a 2008 survey done by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. While salmon have declined, The Yukon delta wetlands support whitefish in abundance, and moose numbers have risen dramatically in the past 20 years. While these populations are rising, however, king salmon numbers have declined.

Salmon harvesting on the lower Yukon illustrates the challenges facing Emmonak today. Elders describe nonstop fishing from 1 June through 15 July in the 1950s. The average annual take was 1,200 king salmon, which sold for 50 cents each. A man could bring in $600.00 in a season, which was enough to see him through the winter. By the late 1990s these commercial harvests had dropped significantly, and they have been non-existent since 2008.

The decline of the commercial fishing economy has a broader social impact on the Emmonak community. Commercial fishing income helps support subsistence activities such as residence at summer fish camps. These camps have been a central activity involving family members of all ages for up to four months a year. In addition to harvesting fish, time spent at these seasonal camps is necessary for other subsistence activities and for educating young people in traditionally proper ways to live. The loss of commercial fishing has contributed to a slow decline in summer fish camp residence.

Social Challenges

The social consequences of the commercial fishery crash are especially troubling. Southwest Alaska has some of the highest rates of suicide and domestic violence in the nation, and Yukon communities have the highest rates in Southwest Alaska. Residents have repeatedly attributed recent suicides to the changes in social and economic conditions. They say that although individuals are responsible for their own actions, they cannot be expected to act appropriately if they are not in control of their land, language, and life. Economic recessions past and present make the situation worse. Lower Yukon residents are using their traditions to solve current social problems. An innovative program of suicide prevention, led by village elders, is making use of traditional practices to rid their communities of suicide. One resident recalled how in the past ritual acts were done in fours, and in 2008 he and other elders worked with students, having them stomp on the ground four times to take away death, then brush it away in four directions. He said, "Since that time, they haven't [committed suicide] up to this day. It was really bad during that time, and I was constantly afraid something would happen to my children."

Yup'ik Cultural Perspective

During the topic-specific gatherings conducted in 2011 elders often repeated the Yup'ik adage, "The world is changing following its people." Yup'ik people see environmental change related to not only human actions, such as overfishing or burning fossil fuels, but also to human interactions. Elders encourage young people to learn traditional rules and proper behavior to act with compassion and restraint in order to reverse negative impacts on their world. They educate young people on the practical skills needed to survive the responsive nature of the world in which they live.

Social and economic conditions, as well as distinctly Yup'ik cultural perspectives, shape the ways Emmonak residents respond to environmental changes. Local knowledge holders want to work with scientists to better understand their past and present and to inform their future. They do this for the sake of the younger generation and to gain respect for their ways of being in the world, which they view as still having value. The Emmonak residents view their work with the CEC staff as part of an active solution to the challenges of change.

For further information, please contact Ann Fienup-Riordan (riordan [at] alaska.net).

References

Fienup-Riordan, Ann, and Alice Rearden. 2012. Ellavut/Our Yup'ik World and Weather: Continuity and Change on the Bering Sea Coast. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Rearden, Alice, and Ann Fienup-Riordan. 2011. Qaluyaarmiuni Nunamtenek Qanemciput/Our Nelson Island Stories. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Fienup-Riordan, Ann. 2005. Wise Words of the Yup'ik People: We Talk to You Because We Love You. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.